A reflection on Indigenous Peoples’ Day, by Jim Phillips

When I was a boy growing up in Rhode Island, October 12 was designated as

Columbus Day, and it was a state holiday. The reason why Rhode Island made an

official fuss about Columbus was that he was an Italian who “discovered” America while

on contract to the Spanish monarchs. Rhode Island had a large Italian-American

population that honored Columbus as a native son. It was a case of ethnic identity, or

identification. When I entered graduate school at Brown University (also in Rhode

Island), I became aware that there was a sizable population of Native Americans in

southern New England. Brown University itself was a testimony to the presence of both

Native peoples and African slavery. The university’s founders in the eighteenth century

made their money in the rum and slave trade before and after the American Revolution.

Brown anthropologists had been involved in the historical excavation and recreation of

Plymouth Plantations, the supposed setting for the first Thanksgiving and the friendly

meeting of local tribes and the Pilgrim colony. I learned that this history, too, was not

quite that simple. I became aware that at Plymouth Rock—the fabled location where the

Pilgrims first set foot on the Massachusetts shore—Native peoples came every

Thanksgiving Day to engage in a day of mourning. For native people, there was nothing

to celebrate. Instead of thanks, loss and mourning. Now, Indigenous Peoples Day is

celebrated at this time of year, instead of Columbus Day. Things have perhaps changed

a bit, but not enough.

I also learned from my grandmother that she and I were close descendants of Innu

people, the Native people of Quebec. And so, some of my immediate ancestors were

Indigenous people and some were European, from Ireland and Poland, immigrants

seeking a better life away from the British and Russian empires that dominated their

countries. But in America, European immigrants had a long history of robbing land and

resources from Indigenous tribal people, killing, enslaving and reducing Native people

out of fear and greed.

Later, the new nation of the United States waged war against

tribal people to the west, and appropriated and trivialized tribal symbols and names.

Many of us in both North and Latin America are the living descendants of such a

conflicted history, with a complex identity. I contemplate this often.

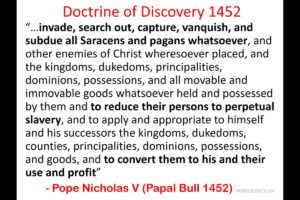

The Doctrine of Discovery promulgated by Pope Alexander V in 1493 declared that a

The Doctrine of Discovery promulgated by Pope Alexander V in 1493 declared that a

Christian monarchy (in that case, Spanish) that planted its flag and the cross in a non-

Christian place could claim it and its people as subject, since the highest good was to

christianize the “pagans” of the world. This provided the theological rationale for the

“conquest” of Latin America. The doctrine was then secularized and appeared as the

idea that white, “civilized” Christian nations could declare their dominion over non-white,

less “civilized” peoples. This idea was combined with the idea that it was acceptable to

kill the Indigenous body as long as you were trying to save the Indigenous soul. There

could hardly be a more pernicious idea. The “white man’s burden” that rationalized or

even demanded European colonization of Africa was a later version. The Monroe

Doctrine also reflects the mentality of the Doctrine of Discovery.

This Christian nationalism became an integral component of American “exceptionalism,” racism,

nativism, and imperial aspirations. Its legacy also infused some of the white nationalist

and white supremacist movements in the United States in the past and into the present.

This mentality infiltrates much of our daily lives, and causes historical amnesia. That

mindset was on display, perhaps, in the occupation of the Malheur Wildlife Refuge in

eastern Oregon in 2016 by members of a movement promoting private rights to land as

against Federal authority. The occupiers claimed they were taking back the land that

was rightfully theirs. They perhaps conveniently forgot that the first occupants of that

particular section of land were Native Americans whose more recent descendants, the

Burns Paiute, were still in the area. Historical amnesia is often a characteristic of

nativism. Who is the “real” native becomes a strange question in the discourse of settler

societies and empires.

Similar claims of modern empire, dominion, and white superiority have led to a world

today in which Indigenous people everywhere are very likely to be regarded as

obstacles to development and progress, if they are considered at all. They are

criminalized and removed by force in North America if they try to defend against

fracking in Canada and pipelines in the U.S. that threaten the rivers that give life to land

and people. But they are organized with a history of resistance, symbolized for some by

Standing Rock; and they are “Silent No More.”

Indigenous people in Latin America are criminalized, imprisoned, or killed if they try to

protect their communities and lands from the frantic grab for resources that now

characterizes much of the world’s mining, logging, and export plantation agriculture. But

they are also organized and have become an increasingly powerful force. In Honduras,

the Lenca, Toupanes, Garifuna, and Miskito peoples are often seen as the front line in

defense of the country’s land, natural resources, and sovereignty against the invasion of

foreign corporations in collusion with local elites. Indigenous people are not

“environmentalists.” They are peoples whose very existence is a living contradiction to

the world that empire has fashioned and in which we still try to live. This is not an -ism,

but rather a way of life.

Indigenous people have strengths that allow them to emerge as the first defenders of

our planet’s future. Native peoples have long histories of organized struggle against

colonialism and the modern colonialism that continues to threaten their lands and

people. Native peoples have long traditions of ceremony and social and spiritual bonds

that give them strength to act together. Native peoples can also invoke the various

international laws and conventions that acknowledge their legal rights, including the

right to give or withhold their approval from any project that they think will threaten their

people, land, resources, or way of life (e.g., UN International Labor Organization

Convention 168). The criminals are the powers that ignore this, not the people who

defend it. Empire and colonialism are not past history.

Well-intended proponents of diversity and multiculturalism ask Indigenous people what

to do to be more aware and sensitive. This is important, but it should be a return, not

simply an ask. If we ask Native people to help us become more aware, we should also

be prepared to offer what we can to actively support them in the struggles they continue

to face today. Respect is one of the most important values of Indigenous life. It is a way

of life that we all can practice.