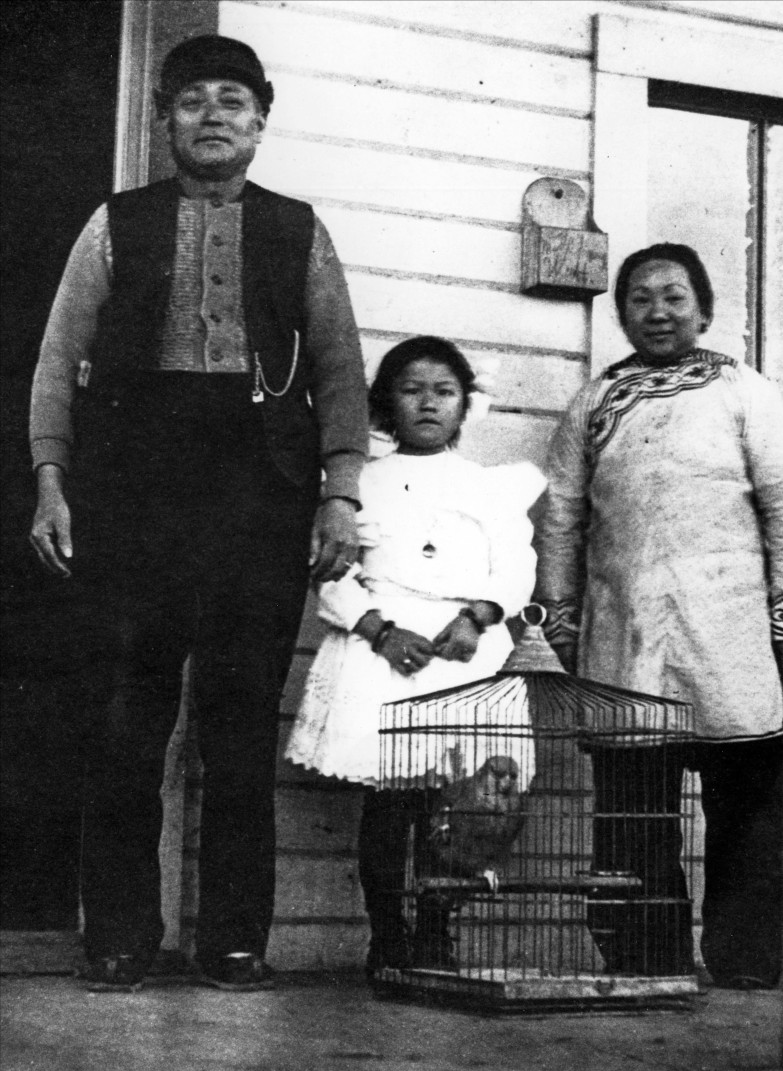

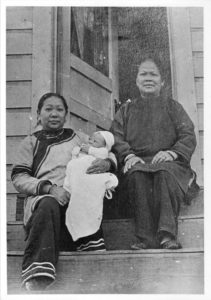

During a formative period in southern Oregon’s history, immigrants from China were one of the largest ethnic groups in the area’s population. Their hard work contributed much to the economic and social development of the region, but they endured considerable racist prejudice, and their contributions were often ignored. Today, as anti-Chinese bias afflicts our society again, it is time to remind ourselves of the contributions of early Chinese settlers and what they accomplished. This is the first of a two-part look at the Chinese presence in southern Oregon.

—Adapted from, A Short History of Tolerance in the State of Jefferson, an unpublished Peace House manuscript.

_______

For centuries, Chinese people have been living and working outside China, fleeing natural disasters, political repression, civil wars, hunger, and poverty in China, just as other emigrant groups have done elsewhere. Groups of Chinese settled in western Mexico under Spanish rule in the late sixteenth century, and Chinese accompanied expeditions to Texas and California in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Chinese carpenters worked for the British-based Hudson’s Bay Company on Vancouver Island in the late 1700s. When news of the 1848 California gold strike reached China, thousands of young and middle-aged peasants borrowed money or accepted indentured work agreements with Chinese contractors to gain ship passage to California. From there, many followed the gold rush northward through the Trinity Mountains, Yreka, and the Klamath River, Rogue, and Applegate valleys.

The Oregon Territory census of 1850 listed only two Chinese in the entire territory. By 1857, according to newspaper accounts, as many as 1200 Chinese were in Josephine county, By 1870, Jackson and Josephine counties had as many as 2500 inhabitants listed as Chinese miners. By then, there were groups of Chinese in several northeastern Oregon counties, and groups in Portland and The Dalles.

At first, most Chinese worked for white-owned mining companies—removing boulders, earth, and mud, and building ditches and canals for hydraulic gold mining. Remains of this work survive today in a few places. As white miners sold or abandoned their claims when the returns no longer seemed to justify the work, Chinese miners bought or took over many of these claims and often made a living on them. A few became wealthy and locally prominent. Groups of Chinese lived in Jacksonville, Ashland, Yreka, and other towns. The Chinese contribution to the gold rush in southern Oregon helped to provide local capital and a basis for the growth of local businesses. It also provided an example of hard work and enterprise.

By the early 1880s, railroad building had replaced mining as a major activity in the region. Considered cheap and reliable workers, many Chinese were hired to help build the lines joining Portland to San Francisco, along the Colombia River, and east of the Cascades, where over one thousand Chinese were employed as railroad workers. They often replaced white workers who quit because the work was too hard or low paying. In northern California, four thousand Chinese railroad workers were encamped near Hornbrook in the early 1880s as they built the railroad grade over the Siskiyou Mountains. They worked six days a week for wages of one dollar per day. The work was hard and dangerous. Landslides and accidents with explosives were constant concerns. In winter, cold, ice, rain and snow increased the problems and hardships. Tons of dirt and rock were moved by hand. Workers died. Many suffered injuries.

When most of the major railroad building was complete after 1887, some Chinese workers stayed on to maintain and service the line from Roseburg to Dunsmuir, through the Rogue Valley. Most of these workers lived in Ashland where there was a repair depot and turntable, the last stop before the difficult Siskiyou grade. Chinese railroad workers lived mostly in what is today know as the Railroad District of Ashland.

Not all Chinese in southern Oregon were miners or railroad workers. From gold mining, some began to accumulate enough capital to open restaurants, laundries, and other businesses to service the local population. Several Chinese became known for their skills as herbalists and healers. Ing Hay served the people of the John Day area. He was reported to provide correct diagnosis and effective herbal treatment in every case, and people called him Doc Hay.

When Oregon became a state in 1859, the state’s laws and local ordnances forbade Chinese and some other groups from owning businesses. But Jackson county effectively ignored the law and allowed some Chinese-owned businesses to operate because they paid taxes that provided a significant income to the county.

By 1870, salmon canneries along major rivers in the Northwest were seeking Chinese workers who were seen as willing to do hard work that others did not want. There were also Chinese workers in a variety of other businesses and farming. At least one became a note real estate broker. Such increased opportunities for work were a mixed blessing. It gave Chinese workers more opportunities but it also raised the fears and animosity of white workers who began to see the Chinese as competitors for jobs. This fear fed an already present prejudice against the Chinese.

Several factors combined to reduce the Chinese population in southern Oregon during the 1880s and 1890s. Hydraulic gold mining declined, major construction of the railroad lines was completed, and ongoing intolerance against the Chinese were factors. The intolerance and the fear of Chinese competition for jobs led the federal government to pass the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882. The Act effectively banned further Chinese immigration, but allowed most Chinese already in the region to remain. Since many of these were single men, the Chinese population began to age without much family replacement. The 1900 census listed only 43 Chinese in Jackson County. By 1920, only 30 Chinese were listed as Jackson County residents, and Jacksonville’s Chinese section had been abandoned, its houses falling into decay.

Beyond its large historical contribution to the region’s development, a Chinese presence remains today in southern Oregon. The annual Chinese New Year celebration in Jacksonville each February reminds us of that in a colorful and lively manner. And there are the personal links and stories. Fong Jong Yuen’s father came from China and was a worker on the railroads in Oregon in the late 1800s. He returned to China where Fong was born. Fong himself later immigrated to Portland, then moved to Medford and became known as Henry Fong. In 1950, he joined with two other Chinese-American partners to start Kim’s Restaurant in a small building on Route 99 near Medford. Kim’s grew into a large and well-established local institution until it closed in 2005. The building was demolished in 2014. Fong died in Medford in 1993 at the age of 78.

______

Historically, the Chinese presence in southern Oregon was much larger and contributed much more to the region than many southern Oregonians realize today.The second part of this article will describe the prejudice suffered by the Chinese community in southern Oregon, the roots of this prejudice, and some of the resistance to it.

—Adapted from, A Short History of Tolerance in the State of Jefferson, unpublished manuscript.

Not all Chinese in southern Oregon were miners or railroad workers. From gold mining, some began to accumulate enough capital to open restaurants, laundries, and other businesses to service the local population. Several Chinese became known for their skills as herbalists and healers. Ing Hay served the people of the John Day area. He was reported to provide correct diagnosis and effective herbal treatment in every case, and people called him Doc Hay.

When Oregon became a state in 1859, the state’s laws and local ordinances forbade Chinese and some other groups from owning businesses. But Jackson county effectively ignored the law and allowed some Chinese-owned businesses to operate because they paid taxes that provided a significant income to the county.

By 1870, salmon canneries along major rivers in the Northwest were seeking Chinese workers who were seen as willing to do hard work that others did not want. There were also Chinese workers in a variety of other businesses and farming. At least one became a note real estate broker. Such increased opportunities for work were a mixed blessing. It gave Chinese workers more opportunities but it also raised the fears and animosity of white workers who began to see the Chinese as competitors for jobs. This fear fed an already present prejudice against the Chinese.

Several factors combined to reduce the Chinese population in southern Oregon during the 1880s and 1890s. Hydraulic gold mining declined, major construction of the railroad lines was completed, and ongoing intolerance against the Chinese were factors. The intolerance and the fear of Chinese competition for jobs led the federal government to pass the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882. The Act effectively banned further Chinese immigration, but allowed most Chinese already in the region to remain. Since many of these were single men, the Chinese population began to age without much family replacement. The 1900 census listed only 43 Chinese in Jackson County. By 1920, only 30 Chinese were listed as Jackson County residents, and Jacksonville’s Chinese section had been abandoned, its houses falling into decay.

Beyond its large historical contribution to the region’s development, a Chinese presence remains today in southern Oregon. The annual Chinese New Year celebration in Jacksonville each February reminds us of that in a colorful and lively manner. And there are the personal links and stories. For instance, Medford resident Fong Jong Yuen’s father came from China and was a worker on the railroads in Oregon in the late 1800s. He returned to China, where Fong was born. Fong himself later immigrated to Portland, then moved to Medford and became known as Henry Fong. In 1950, he joined with two other Chinese-American partners to start Kim’s Restaurant in a small building on Route 99 near Medford. Kim’s grew into a large and well-established local business until it closed in 2005. The building was demolished in 2014. Fong Jong Yuen died in Medford in 1993 at the age of 78.

______

Historically, the Chinese presence in southern Oregon was much larger and contributed much more to the region than many southern Oregonians realize today. The second part of this article will describe the prejudice suffered by the Chinese community in southern Oregon, the roots of this prejudice, and some of the resistance to it.

—Adapted from, A Short History of Tolerance in the State of Jefferson, unpublished Peace House manuscript.