by Rev. John Dear for Waging Nonviolence, published October 21, 2021

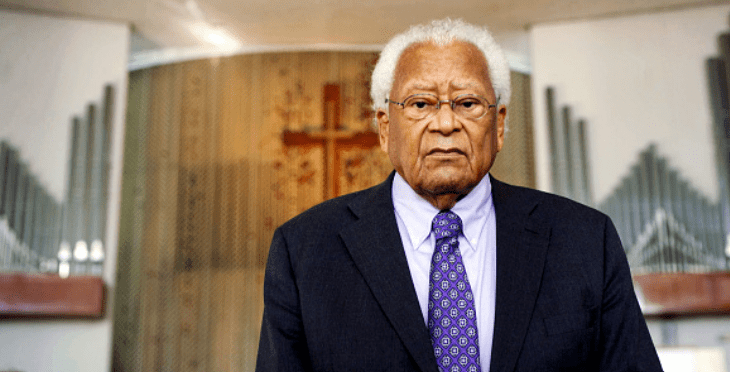

In 1957, Martin Luther King, Jr. described Rev. James Lawson as “the leading theorist and strategist of nonviolence in the world.” For the more than 60 years that followed, Lawson continued to be a key figure that movements turned to for advice. From civil rights campaigns to anti-militarism struggles to labor organizing, Lawson has been the guiding force for active nonviolence and strategic social change. And today, at age 93, he continues to offer a wisdom that’s grounded in the teachings of Jesus and Gandhi.

Born in 1928, Lawson joined the Fellowship of Reconciliation, or FOR, in college, which first exposed him to the nonviolent teachings of Gandhi and Howard Thurman. In 1950, he became a draft resister to the Korean War and was later arrested and spent 14 months in federal prison.

In 1953, he went to India where he spent time with many of Gandhi’s colleagues, including Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru. He returned to the United States in 1956, enrolled in Oberlin School of Theology in Ohio, joined the staff of FOR and met King, who urged him to move to the South. Jim moved to Nashville where he enrolled at Vanderbilt Divinity School.

There he began his legendary nonviolence training seminars that attracted and transformed many young people, including John Lewis, Diane Nash, Bernard Lafayette, James Bevel and Marion Barry. He taught them how to organize sit-ins and nonviolent actions to confront segregation. His workshops led to the Nashville sit-in movement and desegregation campaign. John Lewis called him “the architect of the nonviolent movement in America.”

Jim helped coordinate the Freedom Rides in 1961 and the Meredith March in 1966; helped found the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee; and served as director of nonviolent education for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. While working as a pastor at the Centenary Methodist Church in Memphis, he played a major role in the sanitation workers’ strike of 1968, and invited King to Memphis.

Nonviolence is that quality that comes out of all the great world religions, the notion that the creative force of the universe is love.

In 1974, Jim moved to Los Angeles to serve as pastor of Holman Methodist Church, his base for the next 30 years. For many decades, he has spoken out against racism, and challenged U.S. military involvement throughout the world. He has worked with Janitors for Justice and other unions in Los Angeles, and continues to teach and offer workshops on active nonviolence to this day, including a week-long annual institute. Last year, he gave a fiery and powerful eulogy at John Lewis’ funeral.

Earlier this month, on Gandhi’s birthday, I had a public conversation with him through the Beatitudes Center for the Nonviolent Jesus, my new non-profit organization. We spoke on Zoom about how he came to embrace nonviolence, the need for Christianity to undergo revolutionary change and the critical role of labor unions in transforming our society.

You’ve been teaching, practicing, experimenting with and organizing nonviolence your whole life. Has your understanding of nonviolence changed over the years, and how do you define nonviolence today?

It is hard to define nonviolence. I think it is Gandhi who first used the term nonviolence, and he does maintain in his book “Nonviolence in War and Peace” that the term “nonviolence” is his translation of the Jainist theory of ahimsa. So Gandhi translates ahimsa as “Do no harm; do no injury.” Jainism was an ancient religion of India, begun around the time of Jesus of Nazareth. So that’s one definition that I cling to. It is not specific, but it allows me to live, to function, to practice.

But the other thing that Gandhi says in that same volume is that nonviolence is love in action. Nonviolence is compassion and truth in action. He of course put together the word “satyagraha” to further explain tenacity in truth, tenacity in the soul, tenacity in God, tenacity in struggle.

So for me, nonviolence is that quality that comes out of all the great world religions, the notion that the creative force of the universe is love, that God is love, and that love is all encompassing. Gandhi insists — and I think this is Gandhi’s great contribution — that the creative force of the universe is the only force that can cause the human race to do God’s will on Earth.

And nonviolence is power. It is not, as I was originally told in college in 1947, just persuasion. Persuasion is a form of power. Aristotle says that power is the capacity to achieve purpose. It is a God given gift of creation to human beings. Nonviolence has its deep roots in the long journey of the human family as so many people operated out of love and truth in spite of all that was raging around them.

As Gandhi and King also said, nonviolence is the science of how you create your own life in the image of God. Nonviolence is the science of how you create a world that practices justice, truth and compassion. Gene Sharp was the first scholar to pull together the science, the methodology of nonviolence, the 198 tactics and methods that human beings have used over four or five or six thousand years. We’re still learning about nonviolence as the science of bringing about personal and social change and establishing a world where all of life is honored.

The culture of racism, poverty and war says we’re powerless; there’s nothing we can do. Can you speak more about nonviolence as power, and as a methodology and a strategy for social change.

I continue to insist, that yes, you have to build your life around nonviolence and live a nonviolent lifestyle. There’s a huge range of practices and styles. I like to use the term these days, “the religion of Jesus,” to indicate that nonviolence is the way one discovers how to live. We have to ask not, “Are you saved?” but rather, “In light of the universe we’ve inherited and the gift of our lives, what kind of human beings ought we be? What kind of human beings does the God of the universe require of us?”

Part of the nonviolent revolution is to struggle against those power-brokers who want the world under their domain rather than under the will of God.

I think methodology is an important part of how we live. Every single one of us has a personal, daily routine, and it’s different for each of us. I try to maintain a lifestyle that reflects for me personally the religion of Jesus, and I do this very poorly. But methodology and strategy are critical. Both of them mean that you have to plan and scheme if you are going to exercise the power of truth and love. That won’t happen by accident.

Also there are millions of people around the world who do exercise daily care for life, for their children, for their village, for the street where they live, for their community, for their nation. Far more millions of people faithfully follow the life of love than we know.

Unfortunately, we have inherited a world that is largely dominated by power-brokers of one kind or another. Part of the nonviolent revolution is to struggle against those power-brokers who want the world under their domain rather than under the will of God. That is a struggle that goes on and on. A major contribution of Gandhi is that if we follow the path of love and truth, compassion and care, we will one day shape the Earth more into God’s will.

You have spent your life trying to teach Christians and the world that Jesus is nonviolent. My contention is that, as Gandhi said, Jesus was totally nonviolent, and if you want to follow this guy, you have to try to be as totally nonviolent as you can. Please share more about the nonviolence of Jesus, any thoughts that would help us understand, embrace and follow his nonviolence.

If I ever had any doubts about your question, they were largely obliterated by the time I was eight years old. Growing up in the streets of Massillon, Ohio, from the age of four, I experienced racist epithets that were directed at me. My custom was to fight back with my fists. My brother Bill and sister Daisy also fought back. In the first grade, I had a certain amount of fighting to do because the other boys wanted to fight me. It was never on the school ground, but on the street going to school or on the way home.

At age eight, in the spring of the fourth grade, I slapped a boy who yelled racist epithets at me on Main Street. And for the first time, when I returned home from this errand for my mother, I told her about the incident. She continued to do what she was doing in the kitchen and without turning around to face me, responded, “Jimmy, what good did that do?” And there was a long period of silence in the house as I heard her voice telling me who I was — that I was loved, that I belonged to God, and that we were a family of the church, and how important that community was to us, that I did not need to use my fists on anyone. Her last sentence to me was, “Jimmy, there must be a better way.”

So from then on, I was confirmed in my life, which was already committed to the faith and the church, to St. James Methodist church where my dad had been the pastor. I determined that from now on, on the playing field, for example, I would not get angry anymore because some youngster in the game hit me in football or basketball inappropriately.

So from that time on, there has been no compromise for me that the way of Jesus is the way of truth and love and compassion. If you go to the book of Luke, chapter four, when Jesus returns to Nazareth, you’ll find a story about how the men in the synagogue in Nazareth became very angry at him. The last verse of the story says that — as they dragged him out of the synagogue, dragged him through the streets of Nazareth, which was a very small community — they took him to the precipice, and they were going to throw him over the precipice, “But he made his way through the midst of them and went on his way.” I maintain that represents one of the ways in which Jesus walked and lived. He did it with the spirit of nonviolence and compassion. He did not imitate the folk who were angry at him.

But I have every confidence that Christianity is not following Jesus adequately. Christianity has become the most powerful religion in the world because of its linkage with the Roman Empire in the fourth century. The Roman Empire and its theology made some changes to the teachings and writings of Jesus. I have no doubt.

Christianity, as the most powerful religion in the world, must break with the use of that power, which has created so much havoc — including the conquest of nations and telling other people around the world that their culture, their religion, is wrong and they must be baptized. We have a lot of baptized people in the United States who are deeply enmeshed in the culture of sexism, racism, violence and what I call “plantation capitalism.”

As I read and reread the Bible, and especially the books about Jesus, I know full well that Christianity has to undergo a basic revolutionary change. That’s been a part of my mission, by being in the local church. I’ve had five pulpits across my lifetime — two in Ohio, two in Tennessee and one in California. From a very early age, I was committed to working at the level of the congregation, which I happen to feel very strongly and very good about.

I named my new organization after the Beatitudes, the opening section of the Sermon on the Mount, which Gandhi read from every day, in his morning and evening meditation sessions. Can you share any recent insights with us on the Beatitudes and the Sermon on the Mount.

The book of Matthew, chapter five, starts with the Beatitudes. The last 10 verses deal with a very important issue. It’s where Jesus says, “You have heard it said, you shall love your neighbor and hate your enemy, but I say to you, love your enemies and pray for your persecutors.” It’s in those last verses, he deals with the question, “What do you do when you have an enemy, when you see the enemy?” You pray for them, you love them.

So he says, “If they force you to go one mile, then concede and go with them two miles.” I think that this is an experience that actually happened to Jesus more than once in occupied Palestine, Galilee and Judea. Scholars have discovered an ancient Roman Empire rule that when a Roman official or legionnaire met a person on the roadway, he could say to that person, “Carry my bags for one mile.”

[I can imagine] Jesus walking from Nazareth to Capernaum and meeting a Roman soldier. As he approaches him, he sees that this legionnaire is about his age. As he gets close, that legionnaire says, “Boy, I need you to carry my pack.” By Roman law, Jesus has to take the pack, irritated as he may have been. He takes the pack, and may have to return from the direction he has come. As he looks at this Roman soldier who’s about his age, he begins to introduce himself. And he asks the man where he’s going, where he’s coming from, how long he’s been a legionnaire, and is he stationed in Galilee or Judea? And within a quarter of a mile, these two people are in a deep conversation about themselves, because the legionnaire is lonely, as he would be, for his home. And they talk. And before they have gone a half a mile, Jesus sees this young soldier as he views himself.

I maintain that in those last 10 verses especially, in the Beatitudes, and all of Matthew 5-7, Jesus is telling us that you have to strategize your way of life if you’re going to try to live a life of truth and love. It has to be planned. He gives some suggestions on how you do this: turn the other cheek, walk another mile, pray for them.

Gandhi said that unless a democracy moves toward nonviolence, it will inevitably turn into fascism. Perhaps we’ve never really had a full-on democracy, but we are certainly experiencing fascism now — white supremacy, Trump, systemic racism, voter suppression and permanent warfare. So I want to ask about your diagnosis of the reality we’re facing today, and your thoughts about nonviolent movements today.

I rarely use the word “fascism” to describe the United States. I use the word from the Declaration of Independence, which is “tyranny.” Because it’s important to keep our origins in place, in our thinking. So “tyranny” is my word.

I see myself as being challenged and provoked to try to do what little I can do to establish the rule of God on Earth as it is in heaven. I’m challenged and provoked and saddened by my own inefficiency and incapacities, but I am much more provoked to do all that I can do day by day.

The great cause of the tyranny coming to the foreground and of the confusion today comes from where the nation has been — decimating the population of [Native Americans], which may have been as many as 11 to 15 million people; the hanging of white women as witches; the establishment of Africa as the “dark continent,” using Africans as slaves, and 400 years of slavery and segregation. This country has been run by big wealthy landowners — using what I call “plantation capitalism.”

But in the 1950s, 60s, and 70s, we began the challenge of changing from the country that was into a country that we cannot yet see, which we know can come about. The old country is clashing with the movements of the mid-20th century that challenged all those presuppositions — that we were “an exceptional land,” as Reagan said, “a civilization that could not be destroyed as so many others were destroyed previously.”

I maintain that the issue is not Republican vs. Democrat. It’s too bad we don’t have a political party that wants to fulfill “We hold these truths to be self-evident” and “We the people of the United States in order to form a more perfect union.” We do not have a political process except the political process at the grassroots level. Congregations are aroused and reforming themselves. Unions are aroused and changing themselves. Almost all unions are grappling with racism and male domination and sexism inside the union.

I maintain that the issue is not Republican vs. Democrat. It’s too bad we don’t have a political party that wants to fulfill “We hold these truths to be self-evident” and “We the people of the United States in order to form a more perfect union.” We do not have a political process except the political process at the grassroots level. Congregations are aroused and reforming themselves. Unions are aroused and changing themselves. Almost all unions are grappling with racism and male domination and sexism inside the union.

So I maintain that the clash between the old history, which has been severely challenged by a nonviolent movement as never before, that was extremely revolutionary, continues. This is the clash in our nation today.

The white men in our country who have lived by the demands of sexism, the conditioning and oracles of racism, and a narrow Christianity of domination — who have lived by violence, hatred, and anger [over the loss of jobs] — know that there can be no going back. That’s the clash.

I think the key to the future is the movements in our country that will transform our country from being the symbol of the Roman Emperor Constantine into massive signs of love, equality and truth.

Let me end by asking you about your friend Martin King and thoughts about him that you would like to share. I don’t know if you’ve seen the museum display in Atlanta, where they have King’s suitcase from April 4, 1968. In it, you can see a manila folder, which has written on it, in his handwriting, “The Meaning of Hope.” My thought is that King was grappling with the meaning of hope, because things were becoming so hopeless. That’s a profound spiritual teaching. In other words, we’re just going to keep doing this work, come what may.

I think Martin Luther King Jr. must be given credit for being the one who insisted in Western civilization that the way ahead must become the way of nonviolence. He said nonviolence is a power tool, nonviolent love is the power of God for life, for giving life and creating life and hope.

From the Montgomery bus boycott through the next 13 years of his life, until he was essentially assassinated like a crucifixion for his life and work, Martin King made the Gandhian message that we either go forward with nonviolence or self-destruction.

The ability to vote is significant, but voting is not as significant as being an engaged citizen.

I’m grateful that I met Gandhi through his books and that I came to know Martin King and we became fast friends and colleagues. We were planning the future at the time of his assassination on April 4, 1968. He was an advocate for justice and truth, elected so by the people of Montgomery, and he carried out that role in a magnificent fashion.

King was influential in the Montgomery Bus Boycott, the sit-in campaign of 1960, the Freedom Rides of 1961, the Albany desegregation campaign of 1962, the Birmingham desegregation campaign of 1963, and the Mississippi summer of 1964, which directly produced Head Start [the federal program that provides comprehensive early childhood education and health services to low-income children and families]. Head Start was created by Black women and a white volunteer in Greenwood, Mississippi. The Voting Rights Bill of 1965 is not as critical as Head Start, the 1964 Civil Rights Bill, or Medicare and the immigration bill that the Johnson administration and the Democrats passed in 1965.

The ability to vote is significant, but voting is not as significant as being an engaged citizen. The citizen who takes to heart “We hold these truths to be self-evident” is going to vote on the right side of human history, and not vote conventionally to maintain the status quo or worse. Voting as an instrument of nonviolence is a part of being a human being who wants to become fully alive, wants to be fully an agent of love and compassion.

Audience question: I teach nonviolence at a large university, and my students seriously question nonviolence. We study your Nashville seminars that launched the sit-in movement. What strikes me is your confidence in leading those trainings in Nashville. What was it like in the midst of leading those trainings to hear young people question nonviolence, and help them go for it?

I almost always begin with a new set of people by saying you cannot accept the notions of nonviolence, the methodology and spirituality of nonviolence, because you have been raised in a very violent society. Western civilization has been so violent. Europe over recent decades has been reducing its level of violence but the United States has continued to increase its level of violence. So I begin with the notion that what Gandhi and Jesus taught, and what we taught in the civil rights movement is incomprehensible to the Western mind weaned in the United States. It requires a reversal in the way in which you have learned to think conventionally.

Out of my background and parents and ancestry, I’ve learned that you have an ongoing battle, that most people are taught to hate and support violence and have a violent life. So I make the assumption that I’m not speaking to people who can see Jesus. When I start teaching again in Northridge in January, I’m not addressing a class that has been conditioned to see the nonviolent movement. And in the Black community, where we have voices yelling all the time in anger against racism, I’ve started in the same way constantly.

We are not a nonviolent society. There are, however, millions of people in our nation who practice compassion and care and the sacredness of life, and they appreciate their own lives so much that that they try to appreciate all humankind.

We need massive campaigns of nonviolence until they are a national movement that will shake our nation upside-down.

But racism is deeply embedded. I’ve met over the years white people who never met a black person before. In regional Midwestern conferences of the Methodist Church, I’ve had white high school girls from Minnesota ask my permission to rub my skin to see if my color would come off.

Nonviolent demonstrations scare a lot of people because they put an ethical contrast on the public scene. In the 60s, many times in the demonstrations in the South, journalists would write, “This leaves my puzzled. Here are these white men threatening and hurting the black students sitting at a lunch counter. Their behavior is in fact all wrong as they beat up the sit-in people, yet they’re supposed to be people from a superior, ethical place.” So nonviolence is not peaceful in that sense. It dramatizes ethical and moral and spiritual issues that people are asked to think about. We’re constantly asking people to convert and be transformed.

Audience question: What are your thoughts about the New Poor People’s Campaign?

The Poor People’s Campaign is an illustration of the kinds of campaigns we ought to be developing. We need massive campaigns of nonviolence until they are a national movement that will shake our nation upside-down.

Black Lives Matter made a great illustration of this last year. They ran a great campaign that Erica Chenoweth of Harvard says was 97 percent nonviolent, involving perhaps 25 million people in 2,500 different places. It was the police who did most of the violence. It’s the strongest campaign ever, but it needs to be accompanied by many others.

We must have a revolutionary movement of working people. California is moving toward becoming a democratic society, and in large measure, that’s because of labor organizing. I started teaching labor unions nonviolent philosophy and nonviolent struggle back in the early 80s. I had been chair of the strategy committee for the sanitation workers’ strike in Memphis in early 1968 that precipitated the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. on April 4.

I’ve done that work here. Our labor movement has grown to over 200 unions, 800,000 members in Los Angeles County alone. Any number of voices are now saying, “As a union, we have to have compassion for each other. We have to treat each other with dignity and grace. The problems of our members are the problems that the union must be willing to face.” The movement toward democracy in California, the election of two Democratic senators in Georgia and in Arizona, is largely made up of massive union organizing to get out the vote. Local unions sent 1,400 people into Georgia for the election of those two Democratic senators.

I’m not saying, and we don’t believe, that the Democratic Party is the best, safe channel for the social, economic and political change that we have to have. But it’s probably the only channel we have right now.

There’s a democratization process going on from my teaching nonviolence to labor unions. I’ve been arrested more times with working people, striking over labor causes, in Los Angeles, than arrested for civil rights issues in the South. I’m convinced also that our organizing needs to be around the local church and the local unions. If we can get a strong movement built around those two entities, we can turn our nation upside down.

Audience question: The military budget is over a $1 trillion each year, if you add in what the Dept. of Energy spends on nuclear weapons. And that amount of money over 10 years is three times what we’re haggling about lately in social spending. What is the best way to raise awareness about this?

I’m not sure I know the best way. The late Congressman John Lewis told me that he made a terrible personal mistake in not voting against the Iraq war and the Afghanistan war, a grave mistake. It may be that the defense economy is so deeply established that we cannot dig ourselves out of it.

But personally, I think that the work in the United States to break the back of racism, poverty and sexism is the work that can and will show what is holding up the nation from transformation.

In April 1967, when King spoke against the Vietnam war, a large majority of Black people were angry with him, saying he was interfering and hurting the civil rights movement. But today, 85 percent of Black people are opposed to the war system. There’s a great deal of ambiguity because when Black people joined the military and went to Germany, they experienced a quality of life that they had never experienced in the United States. So that’s a problem. We have a task here, but I maintain that we who want peace need to join our local community’s demand for justice as the path toward breaking the war machinery.

Audience question: Do you have any advice for developing a private, individual practice of nonviolence in daily life?

A big question and a good one. If your life is being transformed by love, you cannot keep it to yourself. You have to get involved in your family, your congregation, your union, your social groups, your community — and turn them into agencies of change. That is why Moses, Jesus and Gandhi would agree that the fundamental law of life is: “You shall love God with all your heart and soul and mind and strength and your neighbor as yourself.” There can be no private compassion, as I understand it. The business of discovering the mystery but wonder of love must be lived in such a way as to help the grassroots where we live emerge in powerful form for truth, justice, equality and the Beloved Community.

This conversation has been edited for length.