by Andrea Miller January 21, 2023 for Lion’s Roar

I wondered if I would ever see Thich Nhat Hanh again.

It was 2013, during his final North American teaching tour, and we were at Blue Cliff Monastery in the Catskills. The retreat had just wrapped up, and I’d stayed to interview him. We talked about many things—his family, karma, the key to happiness.

Then at the end, feeling a mix of happy and sad, I put my hands together in gassho. It was wonderful to connect with Thay, as his students call him, but he was getting older, frailer. Would this be the last time I’d see him?

If you think that I am only this body, then you have not truly seen me.” —Thich Nhat Hanh

The next day, almost all of the eight-hundred-plus retreatants were gone, leaving only the monastics, lay volunteers, and me.

In the morning, we were a small group eating breakfast under a tarp.

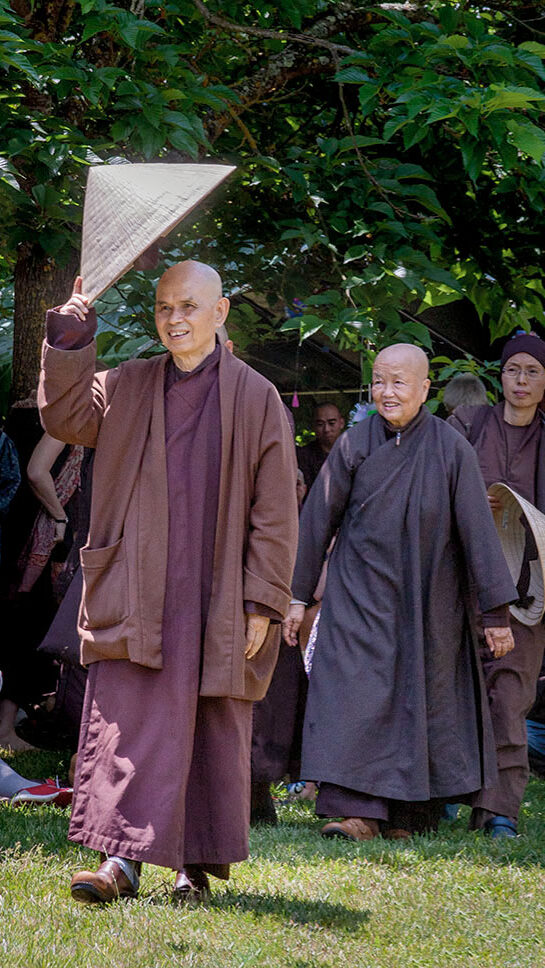

Truth be told, I wasn’t chewing my corn on the cob as mindfully as I could have. But suddenly I was brought back to the present moment by the sight of Thay crossing the lawn, coming toward us.

Thay walked with a couple of brown-robed brothers, taking slow, deliberate steps. His facial expression was placid but profoundly aware. Even in movement, he expressed a stillness I’d never seen in anyone else.

Arriving under the tarp, he went from table to table, greeting people individually and smiling widely as children spontaneously hugged him. When he came to me, he patted me on the shoulder and asked if I was enjoying the dharma book he’d lent me. If I’d had the unselfconsciousness of a child, I would have hugged him.

Then Thay took his quiet leave, crossing back over the green lawn. Again, I found myself wondering: Is this the last time I’ll see him?

Thich Nhat Hanh was still a child when he had his first spiritual experience. On a school trip, he visited a sacred mountain near his home in central Vietnam where a hermit was said to live. Thay, separating from the group, wandered into the forest to look for him. But instead of finding the hermit, he found a natural well with water so clear he could see all the way to the bottom. He scooped up water with his hands and drank deeply. He felt completely fulfilled, his thirst quenched. He didn’t need to meet the hermit—he didn’t need anything. A sentence like a poem sprang into his young mind: “I have tasted the most delicious water in the world.”

At age sixteen, Thay began his Buddhist training as a novice monk at Tu Hieu Temple in Hué. Thay’s teacher, Thich Chan That, was very fond of him and taught him to bring mindful concentration to every task, be it tending cows, harvesting rice, or just shutting a door.

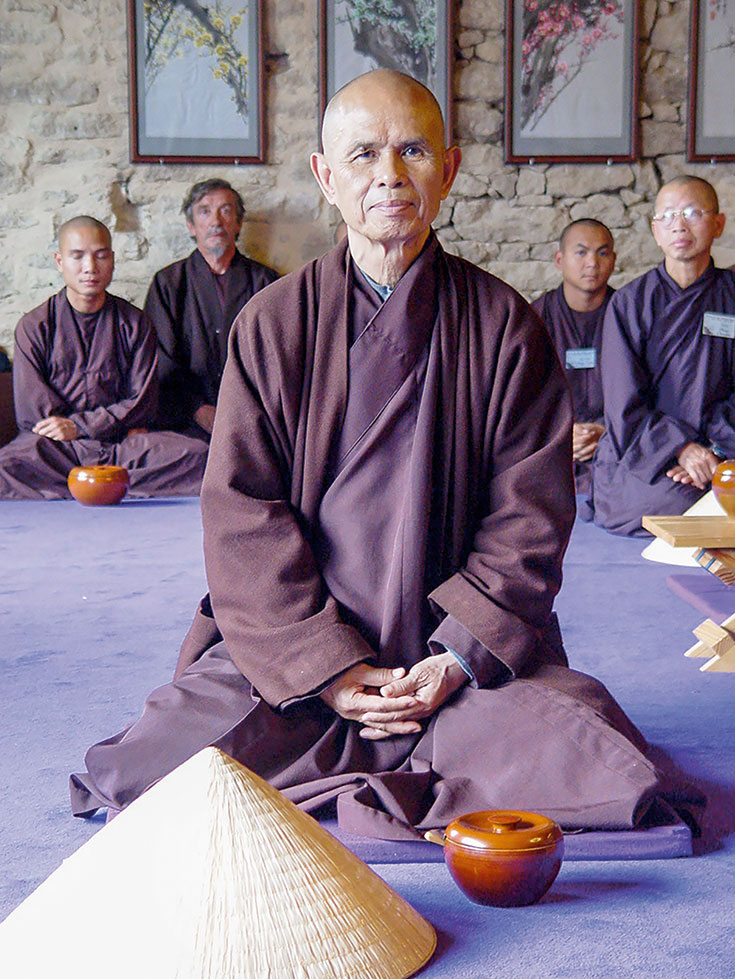

Once, Thay was visiting another temple with his teacher when he saw a Zen monk sitting beautifully straight on a wooden platform. “In my heart as a novice,” Thay later recalled, “there came a vow, a longing, to sit like that. … I would not need to do anything. I would not need to say anything. I would just need to sit.”

Vietnam was suffering under Japanese occupation and French colonial rule. When the Second World War ended in 1945, a dire famine broke out. Stepping out of the temple and into the streets, Thay would see the bodies of people who’d starved to death. “Suffering impels young men and women to go out and join the revolution,” he later said. “As a young person in such a situation, you have to do something for your country.”

Many young Vietnamese monastics embraced Marxism. Thay, however, believed a reformed, socially conscious Buddhism was the key to relieving his country’s suffering, and he set about sharing his vision. By the time he was in his mid-twenties, he’d penned several books and was renowned for his fresh, insightful perspective.

From 1946 to 1954, war raged between colonial French forces and the nationalist Viet Minh. French soldiers repeatedly raided Buddhist temples, searching for resistance fighters and demanding food. Despite being nonviolent and unarmed, monastics were killed, including some of Thay’s friends. When the Geneva Accords officially ended the conflict, Vietnam was split in two, and the seeds of America’s war with Vietnam were planted.

Meanwhile, in Saigon, Thay was cofounding the An Quang Pagoda, which would host a reform-oriented Buddhist institute. In 1954, he became its director of education and spearheaded an innovative program for young monastics, which combined traditional Buddhist education with science, math, history, literature, foreign languages, Western philosophy, and creative writing.

In 1956, he was made editor-in-chief of Vietnamese Buddhism, the magazine of the National Buddhist Association. Catholicism was the dominant force in South Vietnamese politics, and Thay used his prominent position to consolidate Buddhist groups to help protect Buddhist traditions and customs. But as a reformer, he met intense resistance from conservative Buddhist elders.

On a personal front, Thay experienced what he described in his journal as the greatest misfortune of his life: his mother passed away. “Even an old person doesn’t feel ready when he loses his mother,” he explained later. “He feels as abandoned and unhappy as a young orphan.”

Then Thay had a powerful, healing dream in which his mother was young and vibrant again, and he spoke to her without any grief. When Thay awoke, he had the insight that being and nonbeing, birth and death, are just concepts. The idea he’d lost his mother was only an idea; it wasn’t the truth.

“Being able to see my mother in my dream, I realized that I could see my mother everywhere,” he wrote. “When I stepped out into the garden flooded with soft moonlight, I experienced the light as my mother’s presence. It was not just a thought. I could really see my mother everywhere, all the time.”

“Some young people are angry with their father,” Thay said at my first retreat with him, at the University of British Columbia in 2011. “They cannot talk to their father. There is hate.”

My own father had left us when I was four. One day, my mother and I came home and there was a note on the table. He’d gotten on a plane to a faraway city where a woman was waiting for him. I didn’t see my father for two years.

Time went on, I grew up. Then one night while I was sleeping, the phone rang. It was him, drunk. “I have cancer,” he said. Less than a year later, I was with him as he took his last, gasping breath. In his death, my father abandoned me again, and this sparked a rage that was all mixed up with grief.

Now I was in a university gym turned dharma hall. Thay, who was sitting onstage flanked by pots of orchids, was addressing the children sitting on the floor directly in front of him. But the adults were listening just as raptly.

“If you look deeply into a young man,” Thay said, “you will see that his father is fully present in every cell of his body and he cannot take his father out of him. So, when you get angry with your father, you get angry with yourself.”

Imagine, Thay said, if a plant of corn got angry at the grain of corn from which it sprang.

“We are the continuation of our father and our mother, like the plant of corn is the continuation of the seed of corn,” he taught. “Your father is in every cell of your body; your mother is in every cell of your body. So, when your father dies, he doesn’t really die. He lives on in you, and you bring him into the future.”

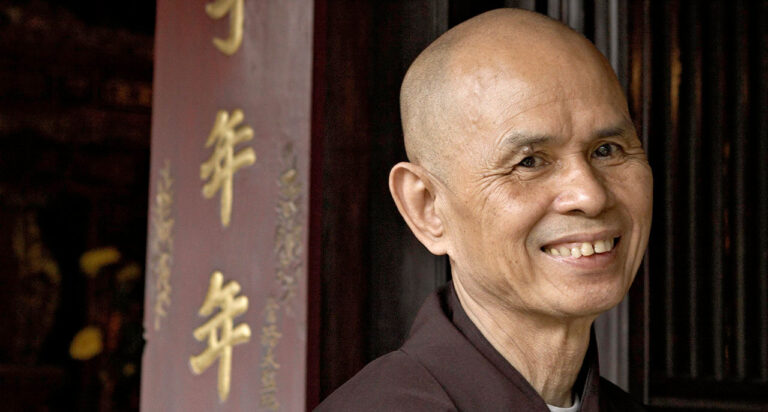

After thirty-nine years in exile, Thich Nhat Hanh returned to his homeland in 2005, where his teachings were attended by thousands. On a visit in 2008, he comes through the gate of Tu Hieu, his root temple in Vietnam. Photo by Paul Davis.

According to Thay, if we’re angry with our father or mother, we have to breathe in and out, and find reconciliation. This is the only path to happiness, and if we can live a happy, beautiful life, our father and mother in us will be more beautiful also.

“During sitting meditation,” said Thay, “I like to talk to my father inside. One day I told him, ‘Daddy, we have succeeded.’ That morning, when I practiced, I felt that I was so free, so light, I did not have any desire, any craving. I wanted to share that with my father, so I talked to my father inside: ‘Daddy, we are free.’”

In the late fifties, Thay spent a month in a Saigon hospital where, it’s believed, he almost died. The death of his mother, the turmoil in his homeland, and the opposition of the Buddhist hierarchy to his progressive ideas had left him suffering from acute insomnia. His body was weak, he was depressed, and his sense of hope was all but snuffed out.

But Thay had a hunch: if he could achieve complete awareness of breathing and walking, he’d be able to heal. As a young monastic, he’d learned the principles of following the breath and slow walking meditation. Now he experimented with combining his breath and steps while walking more naturally; instead of counting only the breath, he counted the steps and breath in harmony. This turned out to be an effective way for him to embrace his despair without being swept away by it, and he recuperated.

In 1959, while giving a lecture series for university students, Thay met Cao Ngoc Phuong, the future Sister Chan Khong and his closest collaborator. She was just a young biology student but was already leading social work projects in the slums of Saigon.

In 1964, a great flood hit war-torn Vietnam. The most devastated populations were those living in conflict zones, where virtually no one dared deliver aid. But Thay and Phuong were willing. They organized a small team to travel by boat from village to village, distributing food, knowing they could be shot at any time. They met people whose whole families had drowned, children injured by gunfire, and mothers who urged them to take their babies because they saw no other hope for them.

In 1965, with the war against Communist North Vietnam going badly, American combat troops entered South Vietnam for the first time. With the violence escalating, Thay and his friends reached out to prominent intellectual and spiritual leaders in the West, asking them to speak out against the Vietnam War. Thay personally wrote to civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr., and the two men bonded.

Meanwhile, Thay established the School of Youth for Social Service (SYSS), a grassroots relief organization that mobilized young people to go into villages devastated by war and poverty. The young idealists set up medical centers and schools, organized agricultural cooperatives, and resettled the homeless. Being neutral, they angered both sides in the war.

In early 1966, Thay founded the Order of Interbeing, a community dedicated to his vision of a modern, socially engaged Buddhism, and following a revised and expanded version of the ten bodhisattva precepts. Since fanaticism leads to war, Thay made nonattachment to views a cornerstone of the order. The original six members included Cao Ngoc Phuong and another young woman, Nhat Chi Mai.

A few months later, Thay embarked on an intense, three-month speaking tour of nineteen countries, calling for peace in his homeland. In Washington, just two weeks into that tour, the situation came to a head. Thay presented a proposal for ending the war in Vietnam that included a schedule for the withdrawal of U.S. troops, and the government of South Vietnam immediately branded him a traitor and revoked his right to return home. He was exiled.

In 1967, Thay received an onslaught of devastating news. His student Nhat Chi Mai immolated herself as a plea for peace; eight of his SYSS students were kidnapped and never returned; and five of his young SYSS social workers were led to the bank of a river by armed men and shot, leaving only one survivor.

When Thay cried, a friend tried to comfort him, saying, “There’s no need to cry. You are a general leading an army of nonviolent soldiers. It is natural that you suffer casualties.”

“No, I am not a general,” Thay replied. “I am just a human being. It is I who summoned them for service, and now they have lost their lives. I need to cry.”

The following year was again marked by loss—the assassination of Martin Luther King. Thay had been instrumental in persuading him to take a stand against the Vietnam War, and the first time King publicly did so, he quoted from Thay’s book Lotus in a Sea of Fire. King had nominated Thay for a Nobel Peace Prize, and Thay had told King that the people of Vietnam described him as a bodhisattva. In the face of the tragic assassination, Thay made a deep vow to continue building what King had called “the beloved community,” not only for himself, but for King also.

On the fiftieth anniversary of Martin Luther King’s famous “I Have a Dream” speech, I was attending that retreat with Thich Nhat Hanh at Blue Cliff Monastery.

To mark the anniversary, many of the retreatants gathered under a tent to ring a large bell. Breathing in, breathing out, we formed a messy, accommodating circle as a man read one of Thay’s poems and the rest of us repeated it. We were a powerful human microphone that could be heard even over the hard rain that was falling.

I walk on thorns, but firmly, as among flowers. I keep my head high. Rhymes bloom among the sounds of bombs and mortars. The tears I shed yesterday have become rain. I feel calm hearing its sound on the thatched roof. Childhood, my birthland, is calling me, and the rains melt my despair.

I thought then of a dharma talk that Thay had given during this retreat. “When you look into tea, what do you see?” he’d asked. “I see a cloud. Yesterday the tea was a cloud up in the sky. But today it has become the tea in my glass. When you look up at the blue sky and you don’t see your cloud anymore, you might say, ‘Oh, my cloud has died.’ But in fact, it has not. When I look mindfully into my tea, I see the cloud, and when I drink my tea, I drink the cloud.

“You are made of cloud—at least 70 percent of you,” Thay had continued. “If you take the cloud out of you, there’s no you left. A cloud has a good time travelling. When it falls down, it does not die. It becomes snow or rain. The rain becomes a creek, and the creek flows down and becomes a river. The river goes to the sea, then heat generated by the sun helps the water evaporate and become a cloud again. Now the cloud has become tea, and Thay is going to drink it. Then what will become of this tea? It will become a dharma talk.”

Thay lived in exile from his homeland for thirty-nine years. As he put it, this made him feel in the early years like a bee separated from its hive, but through strong practice he was able to find his true home wherever he went—in the here and the now.

At first, Thay settled in Paris, where he was joined by Phuong. He became the chair of the Vietnamese Buddhist Peace Delegation, and they set to work organizing international sponsorship for thousands of Vietnamese children orphaned by violence. With the fall of Saigon, Thay and his friends took refuge in Fontvannes, in north-central France, where they named their mindfulness community Les Patates Douces (Sweet Potatoes). Continuing their work to support Vietnamese orphans, they also began sending relief to Vietnamese artists, writers, musicians, and intellectuals.

In 1976, Thay learned that thousands of refugees were adrift at sea, attempting to flee Vietnam. These “boat people” were not only living a nightmare of pirates, storms, and overcrowding; when they did manage to make port somewhere, they were often turned away.

“It’s not enough just to talk about compassion,” Thay later said. “We have to do the work of compassion.” He and his friends rented three large boats and a small airplane and, within a few weeks of searching the seas, they’d rescued some eight hundred people. But all too soon the U.N.’s High Commissioner for Refugees forced them to terminate their efforts.

Thay sought a true answer to war and injustice. As he saw it, angrily demonstrating for peace was pointless. For someone to create peace in the world, they first had to find it in their own hearts, and mindfulness was a powerful tool to do that. So in the 1980s, Thay turned his attention more fully to building mindful community.

In 1982, Thay and his students bought a farm in southern France and converted the dilapidated barns into meditation halls, the sheep sheds into dorms. When they planted over a thousand plum trees, they named their new abode Plum Village.

That first summer, 117 people went to Plum Village, then year by year more people attended their summer retreats. In time, Plum Village would grow to be the largest Buddhist retreat center in the West, welcoming more than 10,000 retreatants a year.

At long last, in 1988, Thay began ordaining his own monastic disciples. Although nothing could be more traditional in Buddhism than monasticism, Thay took a modern approach, creating a fully revised monastic code, establishing greater gender equality, and promoting consensus instead of top-down authority. Over time additional monastic-led mindfulness practice centers were founded, including Green Mountain Dharma Center in Vermont, Deer Park Monastery in California, the Asian Institute of Applied Buddhism in Hong Kong, and Stream Entering Monastery in Australia.

In the mid-2000s, Thay was finally granted permission to return to Vietnam. Despite the Communist government strictly limiting publicity, he was accorded a warm welcome with thousands attending his retreats. In Vietnam today, as in many Asian countries, Buddhism is often seen as old-fashioned, not relevant to the modern world. But Thay’s teachings inspired young people, and many ordained as monastics, finding a home at Bat Nha Monastery in the Central Highlands. This was viewed by the government as a threat. The four hundred nuns and monks at Bat Nha were harassed, and in September 2009, forced out. The monastery was shut down.

In 2014, Thay suffered a stroke leaving him unable to talk or walk. Though doctors believed he wouldn’t survive, he made a remarkable recovery and was eventually able to communicate his wish to spend his remaining days offering his presence and support to his students, first in Plum Village, France, then in Thai Plum Village, Thailand, and later at Tu Hieu, the temple in Vietnam where he’d trained as a novice.

In 2019, I saw beautiful photos of Thay in his wheelchair, enjoying the lush, green gardens of Tu Hieu. It was wonderful to know he was back in Vietnam, full circle. If only I could see him there, I thought. I said wistfully to my husband, “If the kids were older, we could take them.” But any hope I’d get myself and two young kids all the way to Vietnam crumbled when the pandemic hit. Then in January, I got the email from a colleague: “Thich Nhat Hanh has died.”

On January 23, the casket ceremony was livestreamed with thousands of people from all over the world watching from their homes. I watched too, of course.

At Tu Hieu, monastics were gathered, saffron shoulder to shoulder. As the crowds’ singing swelled and broke, a procession of monks carried Thay’s body from his hut to the Full Moon Meditation Hall. There he was lovingly placed in his coffin. Then the coffin was shut tight and festooned with chrysanthemums, his favorite flower.

I had been right, back in 2013. I never would see Thay again in the same form—and now none of us will. But we will see Thay again. Even as the casket ceremony was unfolding, we were seeing him.

“If you think that I am only this body, then you have not truly seen me,” Thay once said. “Every time I see one of my students walking in mindfulness, I see my continuation. There will be a dissolution of this body, but that does not mean my death.”

All the people gathered to honor him, all the people around the world whose messages of gratitude were rolling across my screen, all of us who have been touched by his teachings, all of us reading this now, we are Thay’s continuation.

About Andrea Miller

Andrea Miller is the deputy editor of Lion’s Roar magazine. She’s the author of Awakening My Heart: Essays, Articles, and Interviews on the Buddhist Life, as well as the picture book The Day the Buddha Woke Up.