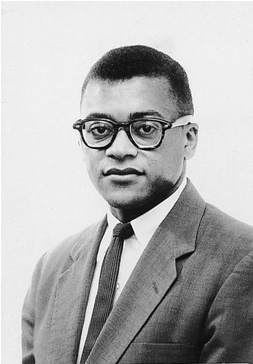

The leading strategist of the Black freedom struggle died Sunday at age 95, leaving a radical legacy and methodology that’s inspired countless movements.

By Ethan Vesely-Flad for Fellowship Magazine

Martin Luther King Jr. called him “the leading theorist and strategist of nonviolence in the world.” To Rep. John Lewis, he was “the architect of the nonviolence movement.” Jesse Jackson simply called him “the teacher.” We at the Fellowship of Reconciliation are blessed to have counted him among our core team of organizers and as a pillar of our spiritually-grounded movement for nonviolent social change. It is with reverence that we remember his life and time with us.

James M. Lawson Jr., who died Sunday at age 95, was born on Sept. 22, 1928 in Uniontown, Pennsylvania. His family moved to Massillon, Ohio, when he was young, and as a deeply Christian family – his father and grandfather were ministers – Lawson began regularly reading the Bible. He had a prophetic and liberatory interpretation of the Gospels from an early age. In a 2014 interview published by Fellowship magazine, Lawson told Diane Lefer, “By the end of my high school years, I came to recognize that that whole business — walk the second mile, turn the other cheek, pray for the enemy, see the enemy as a fellow human being — was a resistance movement. It was not an acquiescent affair or a passive affair. I saw it as a place where my own life grew in strength inwardly, and where I had actually seen people changed because I responded with the other cheek. I went the second mile with them.”

Lawson attended Baldwin-Wallace College in nearby Berea, Ohio, and soon met A.J. Muste, FOR-USA executive secretary, who was on a speaking tour. Muste was renowned as a foremost proponent and strategist of nonviolent direct action. World War II had just ended, a time when FOR members like Bayard Rustin — the Black antiwar and civil rights leader — were imprisoned for resisting conscription. Lawson was immediately inspired to join FOR. Its members had also recently founded the Congress of Racial Equality, or CORE, in Chicago, and Lawson and his brother Phil traveled to participate in CORE trainings in different cities. As he told FOR’s Richard Deats in a 1999 interview, Lawson began reading Tolstoy, Thoreau, André Trocmé, Gandhi, Nehru, and other religious and philosophical theorists and practitioners — and he was drawn even closer to FOR’s commitments.

Graduating college in 1950, as the Cold War grew, Lawson determined he would resist the military draft. He was sent to prison and served 13 months. Upon his release, influenced by his formative engagement with radical thinkers from around the globe, Lawson decided to live overseas. He was drawn to religious ministry, and through his Methodist roots he initially intended to move to Zimbabwe (then known as Southern Rhodesia).

Instead, in 1953, he accepted an offer from Hislop College in Nagpur, India, to teach and coach athletics. Following in the footsteps of FOR members Howard Thurman (1936) and Rustin (1948), who had initiated connections between the African American freedom struggle and Indian self-determination movements, Lawson spent the next three years on the subcontinent in deep study of Gandhi’s life and the satyagraha movement. “I combined the methodological analysis of Gandhi with the teachings of Jesus, who concludes that there are no human beings that you can exclude from the grace of God,” Lawson described to Lefer.

It was while he was in India that the Montgomery Bus Boycott began. “The use of nonviolence on the part of African Americans was a very important thing for me,” Lawson told Deats. Heading home from Asia in 1956, he traveled westward across central Africa, from the Indian Ocean to the Atlantic. “Everywhere I went, I got the question about who Martin Luther King is, what kind of man is he,” Lawson said in a 2022 interview with Nehemiah Stark for the King and Breaking Silence Coalition. He added, “I saw his pictures on the walls of school buildings, cut out of magazines and newspapers, and on village homes in East Africa.”

He returned to Ohio and was completing graduate studies at the Oberlin School of Theology when King, visiting the campus, insisted his expertise was needed — not eventually, but immediately. “I mentioned to [King] that while in college I had long wanted to work in the South — especially because of segregation — as a place of work, and that I wanted to do that still,” Lawson recalled to Deats. “And, his response was: ‘Come now! Don’t wait! Don’t put it off too long. We need you NOW. The movement doesn’t have anyone with your background, your experience.’”

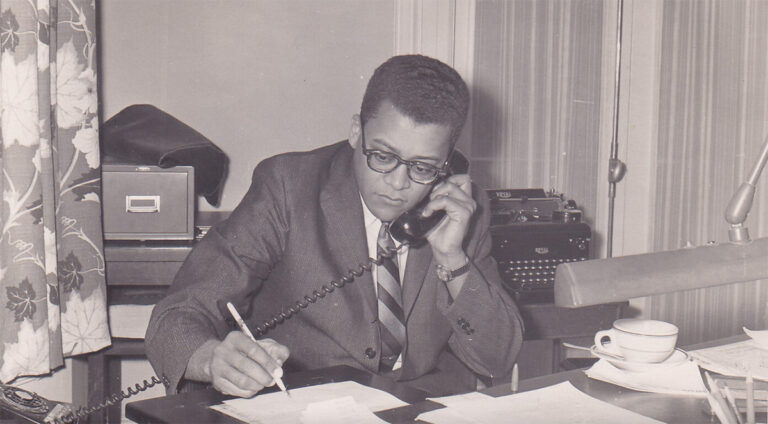

Lawson informed Muste that he had decided to move South. Muste quickly mobilized FOR to offer a paid position as its Southern Field Secretary. In this new role, Lawson would work with Glenn Smiley, a white United Methodist minister based in Los Angeles, who coordinated FOR’s field operations nationwide (and had, along with Rustin, advised King on the strategy for building the Montgomery Bus Boycott).

Basing himself initially in Nashville, Tennessee, and continuing his graduate studies at Vanderbilt, Lawson began working throughout the U.S. South, initially with FOR and then also the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, focused especially on recruiting and training a new generation of direct action activists. Lawson advocated for adapting military language to the nonviolent struggle. In Nashville, his “militant nonviolent” methodology dramatically influenced the trajectory of the freedom movement, including the mass sit-ins in early 1960, then the creation of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee that Spring, and then the Freedom Rides in 1961 (which itself was modeled on a CORE/FOR initiative in 1947 known as the Journey of Reconciliation).

During this time, Lawson was also taking on increased ministerial functions. He spent two years serving a congregation in Shelbyville, Tennessee, then moved to Memphis in 1962 to serve as minister of Centenary United Methodist Church. He spent the next dozen years in that pulpit, working intersectionally with a range of justice movements, including civil rights groups, labor unions and antiwar movements.

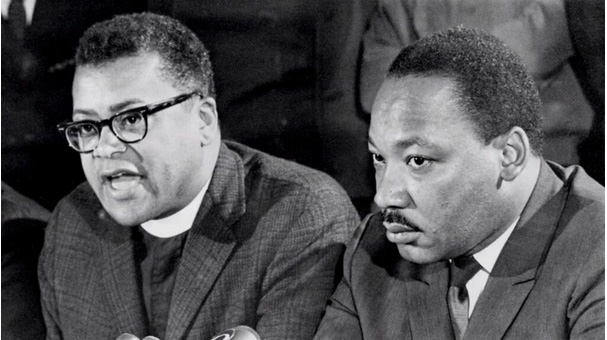

In 1965, Lawson represented SCLC on an International FOR delegation to Vietnam, during which he met Thich Nhat Hanh. As a result, Lawson helped facilitate a relationship between the Buddhist monk, “third way” proponents and King in the following months, which ultimately led to King’s dramatic public stance against the U.S. war in Vietnam during the final year of his life. “U.S. foreign policy towards Vietnam and Africa and Latin America was purely racist and purely plantation capitalist, and purely military,” Lawson told Stark in 2022. “My nation had no interest in the emancipation of Africa and Latin America from our control of the empires.”

Tragically, it was Lawson’s appeal to King to join him alongside his city’s striking sanitation workers that brought King to Memphis in April 1968, when he was assassinated.

In 1974, Lawson was appointed as pastor of Holman United Methodist Church in Los Angeles. He began holding nonviolence trainings in the church, initially as part of the Christian education program, but then opened them to the general public. Returning to the cause of low-wage workers who live in poverty, as he had previously championed in Memphis, he founded Clergy and Laity United for Economic Justice to enlist faith communities in this struggle, and strategically target service-sector jobs. He pushed direct action campaigns, and Lawson was arrested numerous times: “More than in all his work in the South.”

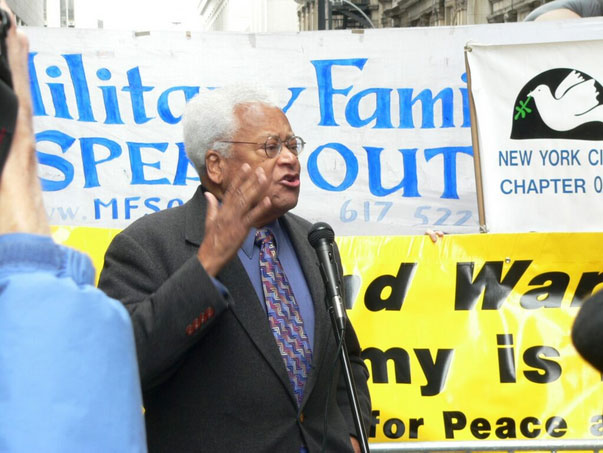

At the same time, he became increasingly conscious of the need to build wider coalitions that would grow intergenerational and cross-sector social movements. He returned to FOR-USA leadership, accepting an invitation to chair its National Council from 1995-2000. In March 2000, seeking to address years of devastating economic sanctions on Iraq, Lawson led an interfaith FOR peace-building delegation to the country. During the trip, speaking to writer Anthony Arnove, Lawson described U.S. sanctions as reflecting the nation’s “opposition to every self-determination movement anywhere in the world … a racist opposition, rooted in a need for domination and control.”

The following year, after Sept. 11, 2001, he helped found Interfaith Communities United for Justice and Peace, focused on the proposition that “religious leaders must stop blessing violence and war.” Then, with fellow freedom struggle veterans Vincent Harding, Dolores Huerta, Grace Lee Boggs and his brother Phil, Lawson co-founded the National Council of Elders, or NCOE, as a framework to share wisdom and movement lessons to next generations. They advised young activists in the Occupy movement, and more recently NCOE’s efforts have led to a revived usage of King’s April 4, 1967 “Beyond Vietnam” speech as a foundation for analysis of our current sociopolitical context.

Referring to that speech in his 2022 interview with Stark, Lawson said, “The United States remains the number one enemy of peace and justice in the world. It remains, in his words, in that speech, the single greatest purveyor of violence in the world.” In words that reverberate clearly in the 2024 electoral season, he continued, “It remains that the United States can go to the aid of Ukraine and fight Russia, but it cannot make voting rights available in Texas or Florida, or Mississippi, or Tennessee for Black people.”

Indeed, Lawson spent his last decades working within peace circles while offering withering critiques that their movements too easily looked beyond the U.S.’s borders. “Only by engaging in domestic issues and molding a domestic coalition for justice can we confront the militarization of our land,” he argued to Lefer. “We must confront that here — not over there.”

Toward the end of his life, Lawson described his “fundamental message” for the next century of struggle, saying “the U.S. must experience a series of nonviolent campaigns that will make what we did in the 20th century look tiny and small and calm in comparison… I can’t try to pretend what all those campaigns ought to be and can be, but … they must be deeply connected with … the deep strategies and philosophies and behaviors of nonviolence that came out of the ‘60s.”

Whether prophetically interpreting the scriptures, challenging America’s original sin with the fierce power of nonviolent direct action, or strategically connecting with other monumental peace leaders, Lawson’s commitment to social justice was relentless and unwavering. We at the Fellowship of Reconciliation are blessed to have worked with and been mentored by him. As we continue to confront the injustices of our times, we know that Lawson’s spirit is walking beside us.