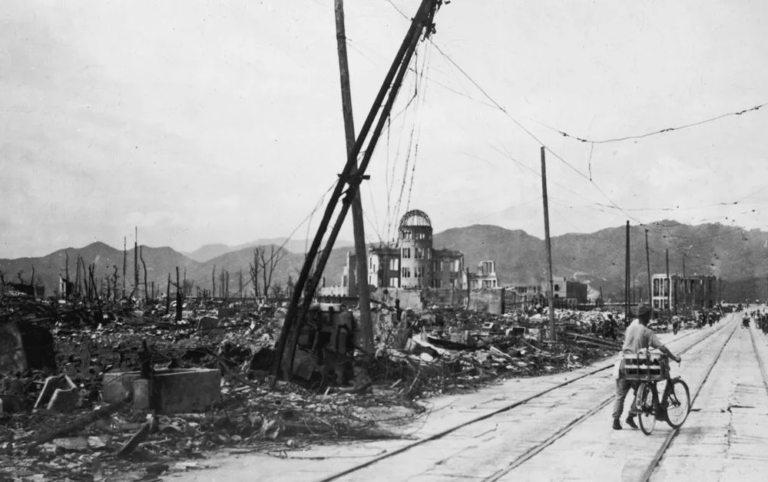

In just a few weeks, people in the Rogue Valley will have an opportunity to once again commemorate the August 6, 1945 U.S. bombing of Hiroshima which, in addition to the August 9 atomic bombing of Nagasaki, killed upwards of 200,000 people. The bombings mark the only time nuclear weapons have been deployed in combat in world history. The annual event will take place on August 6 at the traditional 8 a.m. time, near the entrance to Lithia Park in Ashland.

When the Little Boy nuclear bomb was dropped by the US onto the city of Hiroshima, no one knew for sure how many people would die, or that there would be contamination across generations from the radioactive material scorched into the bodies of Japanese citizens. Even President Truman was said to not have known the scale of destruction and legacy issues that would ensue after the horrific events.

Soon after the bombing, a number of journalists attempted to travel to Japan to report about the effects of the bomb, but were turned away by Occupation forces. Meanwhile, Japanese physicians and researchers accessed the devastated cities to help survivors and they immediately began to observe and take record of the unusual illnesses and symptoms of survivors. At the time, the condition became known as the “Atomic Plague.”

“American officials confiscated [the] Japanese reports, medical case notes, biopsy slides, medical photographs, and films and sent them to the US where much remained classified for years (some for decades),” wrote historian and Professor, Janet Farrel Brodie in an article for the academic journal, The Conversation. The censorship didn’t end there, because the occupying force in Japan created strict guidelines on what could, and could not, be made public.

Brodie continued by writing, “one month after the war ended, Occupation authorities restricted public criticism of the US actions in Japan and denied any radiation aftereffects from exposure to the nuclear bombs.” In the US also, newspapers hardly covered the topic, except to illustrate the bombing of the two cities as historic victories, credited with ending the war. The reasons for the censorship were varied, but a clear objective was to completely omit the impacts of radiation.

One journalist, William Laurence, who had been a science writer for the New York Times, was recruited by the US military and worked for the Manhattan project for two years before the bombing of Hiroshima. He was, according to Richard Daly, professor of Journalism at Boston University, recruited from his post at the Times to write press releases and create strategic communications to normalize nuclear weapons to the American public. According to the NY Times at the time, Lawrence was still a staff reporter with access to nuclear development. He witnessed the Trinity test, among others, and had access to nuclear production sites across the United States.

“It was Laurence who wrote the false press release that the Army used to concoct a cover story [for the Trinity test],” wrote Daly. “The few civilians in the surrounding areas who saw the great flash on July 15 were assured that there was nothing to worry about, just an old ammo dump that had blown up. In fact, the Army was exposing everyone in the surrounding states to their first dose of airborne radiation.”

So it was perhaps not a big surprise that the New York Times was tipped off days before Hiroshima and that Laurence would author the front page spread describing the bombings, with a poetic description that named the bombing as the “entering into a new nuclear era.”

“Awe-struck, we watched it shoot upward like a meteor coming from the earth instead of from outer space, becoming ever more alive as it climbed skyward through the white clouds. It was no longer smoke, or dust, or even a cloud of fire. It was a living thing, a new species of being, born right before our incredulous eyes,” wrote Laurence for the NYTimes in 1945.

Another of the first journalists to report on the deaths in Hiroshima and Nagasaki was Homer Bigart, who wrote for the New York Herald Tribune. He reported the numbers of dead at around 85,000, and while hinting at the effects of radiation, he was unable to document the impacts.

Perhaps the best known and most impactful US reporter who reframed the conversation was named John Hershey. He had been covering the war in Europe under strict oversight of the Allies, but managed to get to Hiroshima, a year after the bombing. He wrote a 30,000 word essay describing life from the viewpoint of six survivors. The New Yorker dedicated an entire issue of their publication and published the entirety of Hershey’s essay, challenging the government narrative that atomic bombs were simply conventional weapons. The descriptive and devastating article had a profound effect on Americans and ruptured the tight censorship fabric that had been successfully covering up the impacts of radiation.

Lesley MM Blume wrote the book titled, Fallout: The Hiroshima Cover-up and the Reporter Who Revealed it to the World, which highlighted the journey and revelry for John Hersey’s courageous reporting. According to her account, the world may have not known it at the time, but the importance of the article could not be overstated.

“Hersey himself later said the thing that has kept the world safe from another nuclear attack since 1945 has been the memory of what happened in Hiroshima. And he certainly created a cornerstone of that memory,” Blume wrote.

The methods the US used to maintain this censorship far exceeded just putting pressure on editorial leadership or burying scientific observations. It included publishing incomplete and false information to expand the use of nuclear technology.

But, as history has it, authentic stories from Japan seeped out of the cracks, and they finally hit the light of day. After Hershey’s article appeared in the New Yorker, articles appeared in the New York Times and publications around the world that described the devastation and lasting impacts of radioactive weapons. So, while the US tried to conceal the truth, the threat that nuclear weapons produced quickly overcame attempts at censorship. It was not long after that when the bombs and munitions using radioactive materials would be separately categorized from their conventional counterparts and condemned for future use.

Clearly this account barely scratches the surface of what was needed to cover up the tremendous radiation effect that resulted from the bombing of Nagasaki and Hiroshima. Importantly also, this does not account for nuclear tests, or any other US military use of nuclear technology. Reports are now readily available that detail the effects radiation can have on people, animals, and the natural world. But we are still kept in the dark, and the topics surrounding nuclear technology are still largely kept under lock and key.

It’s no wonder that people seem to glaze over when asked about the effects of nuclear weapons and energy. One must wonder why most people imagine the larger than life mushroom cloud when they think of a nuclear bomb. Is it because the images of charred bodies and desolate landscape are buried under the rubble?

It’s past time for all of us to face the reality that nuclear risk is not a shadow issue, or something we have no power to change. According to the Bulletin Atomic Scientists, we are closer than ever before to an earth shattering event caused by nuclear weapons, yet proposals are on the table to update the entire US nuclear arsenal.

Sources:

- https://theconversation.com/the-little-known-history-of-secrecy-and-censorship-in-wake-of-atomic-bombings-45213

- https://www.npr.org/2020/08/19/903826363/fallout-tells-the-story-of-the-journalist-who-exposed-the-hiroshima-cover-up

- https://www.npr.org/2005/06/25/4717966/george-weller-reporting-from-nagasaki

- https://theconversation.com/the-little-known-history-of-secrecy-and-censorship-in-wake-of-atomic-bombings-45213

- https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/asia/japan/11778250/Hiroshima-70-years-on-one-survivor-remembers-the-horror-of-the-worlds-first-atomic-bombing.html

- https://www.npr.org/2020/08/19/903826363/fallout-tells-the-story-of-the-journalist-who-exposed-the-hiroshima-cover-up

- https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1946/08/31/hiroshima

- https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/asia/japan/11778250/Hiroshima-70-years-on-one-survivor-remembers-the-horror-of-the-worlds-first-atomic-bombing.html

- https://collections.nlm.nih.gov/bookviewer?PID=nlm:nlmuid-45730570R-bk#pagcte/36/mode/2up

- https://www.yahoo.com/news/american-journalists-covered-first-atomic-142706201.html