Foreword by Elizabeth Hallett, Director of Peace House

A Cat and Mouse Game on the Greenway – Sam Becker reporting on the scarce services and law enforcement practices that harm the Rogue Valley’s houseless community

Foreword by Elizabeth Hallett, Director of Peace House

Peace House is concerned about the treatment of those who are houseless and being rousted from locations along the Greenway when there is nowhere else to go since the current camp in Medford being run by Rogue Retreat is at capacity with twenty-five spaces. There have been some strides made to get the camp operational and this is a wonderful thing. At least five people have been able to access resources that helped them to move into housing, and make room for others who are in need to fill their places. The model shows promise and could be expanded.

Meanwhile, Peace House urges continuing concern and a focus on problem-solving to address houselessness and hunger amongst those who are experiencing the stress of these times without a a pace to live, as well as adequate food and medical care. There is ancient proverb that says that:

“A community is known by the way it treats its most vulnerable, be they elderly, unhoused, hungry or ill.”

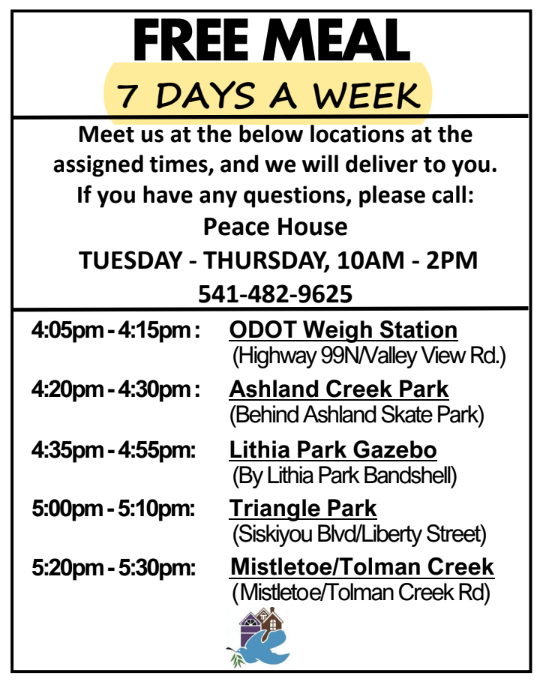

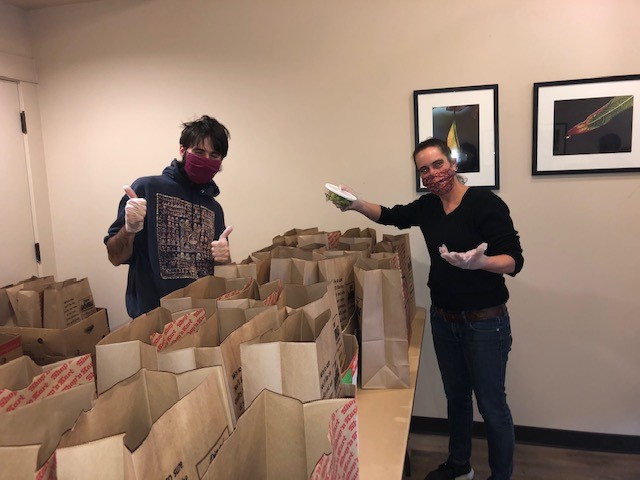

Currently the Peace House Uncle Food’s Diner is serving 120 meals four days a week to those who are experiencing food insecurity. At this writing we are topping 8000 meals served since March 25th. The Monday Meal and Jobs with Justice have also been doing a huge job of addressing houselessness and food insecurity the other three evenings in Ashland. Some of the Greenway folks have benefited from our outreach.

Below is the location and schedule of meals being served in Ashland, whether by the Peace House Uncle Food’s Diner, now it’s 28th year, or the other two programs.

A Cat and Mouse Game on the Greenway – Sam Becker reporting on the scarce services and law enforcement practices that harm the Rogue Valley’s houseless community

| Jul 27 |

https://counterbound.substack.com/p/a-cat-and-mouse-game-on-the-greenway

“We’ve been doing this for eight years,” says an unidentifiable Medford Police Officer, shrouded in darkness, as he walks into a collection of legal encampments along the Greenway.

It is 12:00 am on June 22, 2020. Bright flashlights probe thin tent walls illuminating figures with hands behind their backs, recently handcuffed by the officers. In the same video, released by Southern Oregon Rising Tide, another unidentifiable officer insists “we’re just trying to bring resources out to people.”

In mid-July, I met Arcadia Lopez, a Greenway resident caught up in the June 22 operation. When I asked about the approach used by the Medford Police Department (MPD), she told me the first thing they did was run names, apparently checking criminal records as the first response. “I can’t believe they would automatically assume that you’re a bad person because you’re out here,” said Lopez. Only after they cleared her name did they offer her resources. This tactic, she worried, would deter people on probation or with warrants from accessing the resources they desperately need, like shelter, food, or mental and physical health care.

In March, as COVID-19 infections were picking up, Governor Kate Brown quickly called for Oregon residents to shelter in place. Workers were furloughed, and people were asked to hunker down to curb the spread. Those in Jackson County without homes, however, were asked by law enforcement and city and county officials to shelter in place along the Greenway, the stretch of riparian zone spanning from Ashland to Central Point.

According to State Representative Pam Marsh, who helped coordinate the County’s efforts to assist the houseless population during the pandemic, there were two main concerns that formed an otherwise unlikely coalition to address camping along the Greenway. One side was “focused on the health of this population itself,” Marsh told me. The other side was “focused on the role that the homeless community could play in driving the transmission of the [virus] in the external population.”

Houseless individuals are particularly vulnerable to COVID-19 transmission due to close living quarters and limited sanitation access. To address hygiene concerns and keep the houseless community on the Greenway, staff from City of Medford, Jackson County, and various service providers placed portable restrooms throughout Medford, provided food and basic garbage services to Greenway residents, and offered medical care.

These institutions sought to meet the basic needs of the communities living along the Greenway, but the execution of the program was riddled with errors. According to a Facebook post by Ashland City Councilor and mayoral candidate Julie Akins, Greenway residents waited hours, in some cases, to get the food they were promised. Sometimes it never came. Residents received spoiled meat that caused a number of food-related illnesses. Per a County contract, Aramark corporation, which makes food for Jackson County Jail inmates, paying inmate workers a daily stipend of $1, prepared the food for Greenway residents.

Handwashing stations were not installed near multiple portable toilets, and multiple handwashing stations lacked water or soap. Some portable toilets were clean, others were not. None of them were American Disability Act (ADA) accessible. In an audit done by Julie Akins, around one third of portable toilets had hand sanitizer. Trash cans were nowhere to be found at most of these sites. If our community had been hard-hit by COVID-19, these errors created conditions for the rapid transmission of COVID-19 and subsequent deaths of Greenway residents.

The houseless community voiced their frustration about these inadequate services to Rogue Action Center, an organization of community members working towards economic, racial, and environmental justice at the local and state level. In response, Rogue Action Center Board of Director’s Chair Sarah Spansail wrote a letter to Jackson County Sheriff Nathan Sickler and Emergency Operations Center Operational Group Leader Steve Lambert asking that overhauls be made to the food and hygiene services. Spansail also requested that the displacement of the houseless community be stopped throughout the remainder of the pandemic.

The errors caused by staff from the City of Medford, Jackson County, and various service providers did not happen in a vacuum. They happened in a system built on immense racialized-class hierarchies, the driving force behind houselessness. The system – unaffordable or unavailable housing and health care, over-policing of those without property, and rapid gentrification – favors those in power and leads them to downplay the severity of the complex crises impacting our community

“I knew they were going in,” Pam Marsh told me when I asked her about the midnight sweep on June 22. She proceeded to explain that she asked law enforcement officials whether the operation would be displacing anybody. “They said ‘no,’ they were only going to clean up empty camps.” After multiple accounts of Greenway residents having belongings confiscated and being arrested, law enforcement clearly did more than that. Next time they say “no,” should they be trusted?

In the wake of the operation, law enforcement advanced a narrative through the Mail Tribune, KTVL, and KOBI that the June 22 operation was about mitigating environmental hazards and offering services, not displacement or enforcement. The video footage, and stories like Arcadia’s, which were corroborated by a number of houseless people who declined to go on record for fear of retribution, clearly demonstrate the narrative as one-sided. It’s not just the environmental hazards and services.

“Trash drives people crazy,” said Pam Marsh, when I asked why such strong enforcement exists.

My high-school self would relate. In 2012 and 2013, I picked up over 350 pounds of trash along a stretch of Medford Greenway to fulfill my school-mandated community service hours. After, I spearheaded a citywide initiative to ban Styrofoam food containers in Medford. The Medford City Council passed the ban in spring of 2014. When applying to university, I proudly reflected on my efforts.

“I have been on a mission to ban polystyrene foam (PSF) food containers in Medford, Oregon for eight months. This desire has waxed ever since I adopted and started doing community service on a stretch of pedestrian/bike path as a Sophomore. I originally came to despise PSF (also known as StyrofoamTM) due to the way it looks in nature and crumbles into smaller pieces when I pick it up.”

I grew up and currently live amidst a consumer society in a middle-class household. I conveniently and frequently purchase and dispose of goods. I swiftly externalize the discomfort of trash to the landfill on the north side of Roxy Ann Peak. I effortlessly purchase high-quality goods and return them if they are defective or did not fit. I have a garage where I store all the items I only used once or twice a year.

What I do not have to do is search through dumpsters for my former belongings after they are “cleaned up.” I do not have to abandon my home for fear of being ticketed or arrested for trespassing or related warrants. I neither have to re-purchase belongings nor collect them from charities multiple times a year because the police entered my house and disposed of them.

Mail Tribune’s response to the June 22 operation is titled, “Truckloads of trash hauled out of greenway.” What it fails to mention is how the rhetoric of environmental hazard is being used as a means to displace the houseless community along the Greenway. If trash collection was the goal of the operation, why would law enforcement need to be part of the process? After all, I collected trash on the Greenway as a high schooler. I was all by myself.

If it was trash, then placing routinely-serviced, strategically-placed dumpsters and trash cans, while offering incentives for trash collection would be a good step towards reducing waste.

Sometimes the rhetoric of environmental hazard is more clearly used as a rationale to displace the houseless community along the Greenway. “The main reason for moving the unsheltered off the Greenway is fire danger,” wrote Medford Deputy City Manager Kelly Madding in an email to law enforcement, service providers, elected officials, and advocates. She proceeded to mention that the overwhelming majority of these fires are campfires but neglected to mention that the houseless community uses campfires to cook food and warm themselves.

These are basic needs. What are people supposed to do if they can neither easily access food nor find space in one of Medford’s frequently full shelters? Go hungry, potentially in the cold?

If mitigating fire risk from campfires is the goal, however, houseless people do not need to be displaced. Displacing them may bring in more potential fire fuel and lead to new campfire spots, resulting in more fire risk. Why not designate campfire fire pits and hand out fire extinguishers and cooking stoves to those who rely on fire to cook or for warmth?

The logic that environmental hazards are mitigated by displacing houseless people is brittle, like the sun-baked Styrofoam I picked up in high school. Mitigating environmental hazards from trash and fire does not require the police to displace houseless people. In fact, displacement likely fuels trash accumulation and fire risk.

There’s a whole lot of tension

When I asked MPD Police Chief Scott Clauson whether he thinks the houseless community should be allowed to shelter on the Greenway if the pandemic continues, he told me there were “80,000 residents just in our city that want to use the Greenway.” They “…do not support the Greenway to be a place for the homeless to live.”

“I have to constantly balance that with having compassion for those who are less fortunate,” said Clauson. “I just think that we can continue to connect them to resources.”

Yet, this balance does not exist. MPD prioritizes law enforcement over resource provision, and the resources themselves are woefully scarce.

In September 2019, the Medford City Council started the Livability Team via a $1.2 million investment over two years. The Team, which includes four new officers and a records specialist, is an “…an effort to find a balance between enforcement and outreach and address livability concerns such as homelessness and chronic nuisance houses,” per the City’s website. According to MPD data, between September 2019 and June 2020, Medford Livability Team officers connected 34 people to housing or shelter.

Over the same period of time they wrote nearly 160 tickets for prohibited camping or trespassing.

When asked about the Livability Team, Mary Ferrell, the Executive Directory of Maslow Project, which has provided around $55,000 of emergency food aid and hygiene supplies to at risk youth and their families during the pandemic, said “…there’s at least a perception” the Livability Team is different.

The Livability Team is caught between the law and provision. Law enforcement conflicts with and supersedes connecting houseless people to services – meaning only after Livability officers enforce the law can they provide anything.

Like all other police officers, Livability officers must maintain public space for the “good of the community.” According to Chief Clauson, cleaning up the Greenway can only be accomplished by removing the houseless community and the environmental hazards they produce. Then the trash can be collected and sent to a landfill.

It should come as no surprise, but people are not disposable like trash. The Rogue Valley is strapped for resources, particularly transitional, affordable, and addictions-recovery housing. Houseless people are ticketed and forced to move, but most of the time, Livability officers have nowhere for them to go. They just end up houseless, frequently somewhere else along the Greenway, according to Medford City Councilor and mayoral candidate Kevin Stine.

When asked about this tension, Chad McComas, the Executive Director of Rogue Retreat, an organization that seeks to address the growing homeless epidemic in Southern Oregon through providing housing and case management, bemoaned that the Livability officers “…have a terrible job.” If they provide services to the houseless community but do not drive them away from the Greenway, they are not doing their job to maintain public space. Mary Ferrell told me that Maslow staff frequently hear from members of the houseless community who feel unnecessarily harassed by law enforcement.

“It’s cat and mouse game with the police,” says Pickles, a houseless person living along the Greenway. She told me that accessing scarce resources, like transitional housing, is difficult enough without feeling harassed by law enforcement. Getting back on her feet during previous stints of houselessness was easier because police were not constantly ticketing her for illegal camping and cleaning up her belongings. “There’s no answers where to go besides here,” she said.

The six other houseless people with whom I spoke that day wanted nothing to do with the police. They balked at the MPD’s effort to provide resources, unanimous in their antipathy. All had stories of transgressions. It was clear from these conversations, the police were more of a threat to well-being than they were helping hands.

Livability Team members are police officers, not social workers. Their primary job is to enforce the law, and connecting the houseless community with services is an afterthought. They are there to uphold an institutional agenda. On the ground, this means the removal of people considered to be disruptive. And, often, the main driver of the removal are private and public sector interests that prioritize profit over people.

During operations, like the one on June 22, which are commonly known as sweeps, law enforcement invites service providers to offer resources to houseless residents. When I asked Ferrell if Maslow Project accompanies law enforcement during their late-night sweeps, she told me that they generally decline the offer because they “…don’t want to be viewed by individuals camping as part of what they perceive as the problem.” Instead, Maslow Project reaches out to individuals before the sweeps happen. “If you’re woken up by a law enforcement officer in the middle of the night, it’s going to trigger you,” she tells me.

Medford Police Chief Scott Clauson told me he does not see any tension between houseless folks and police. He proceeded to tout that “All the media outlets have done stories about the relationship between folks and the Livability Team [that] include them giving our guys hugs for the work they have done.” He added that, “I think it’s a national narrative that the police harass the homeless, but that’s not what’s happening here. That’s purely anecdotal.”

The anecdotes from houseless people, statements from two of Medford’s largest service providers, and the Livability Team’s own data suggest otherwise.

Subscribe to Counterbound Monthly to get a book, every month, of local art, essay, and poetry. By, and for, Rogue Valley locals.

Where are the resources?

Livability officers must enforce the law before they can provide services, and enforcing the law inherently reduces their ability to do so. Imagine you are sleeping in the stairwell of a parking structure and a police officer writes you a ticket with bail set at $3,000. Or, imagine you are one of the 49 people who has been given a $250 ticket by Livability officers for smoking in a public park or space between September 2019 and June 2020. Would you want to continue the interaction by asking them for help?

And, even in instances where a houseless person feels comfortable speaking with a Livability officer about the available services, the pickings are slim.

Kevin Stine has seen such interactions first hand. He told me that police ticket people for illegal camping and proceed to give them a piece of paper with resources on it. Handing someone a piece of paper with contact information for under-resourced service providers does not work, residents describe routinely throwing away the contacts. The resources are tight, Stine said, “There’s not enough for everyone.”

When I asked Maig Tinnin, a Tenant Leader for Community Alliance of Tenants, how she navigates the dearth of resources when speaking with people, she told me she tries “to set people’s expectations low.” Waitlists for transitional and affordable housing are woefully long: waits of up to three months for Rogue Retreat’s Kelly Shelter, up to three years long for ACCESS’s affordable housing, and up to four years long for Housing Authority of Jackson County’s affordable housing.

“Those waits reflect the supply of housing we have available, and currently that’s not acceptable,” remarked Pam Marsh. Transitional housing can be essential for figuring out next steps. Marsh bemoans that even if houseless people are motivated to find transitional housing, they generally cannot find it in the Rogue Valley.

Addiction-recovery space is also severely limited. For instance, while MPD, the City of Medford, and Providence partnered on a five-bedroom addictions-recovery house managed by Rogue Retreat this year, MPD Chief Scott Clauson sees a need for at least 100 of those beds.

Sometimes Rogue Retreats’ Kelly Shelter, located near Hawthorne Park, and Hope Village, located southwest of the Rogue Valley Mall, have hundreds of people on their wait lists, according to McComas. Even though Rogue Retreat staff make efforts to contact everyone, many chronically houseless people cannot afford cell phone bills, often lacking mailing addresses. Tinnin notes that the Housing Authority of Jackson County will kick applicants off its waitlists if they do not respond to periodical mailings within ten days. Tinnin asks, “How are you supposed to do that if you don’t have a residential address or have to trek out to St. Vincent de Paul?”

St. Vincent de Paul, a service provider that offers housing, food, hygiene, counseling, and other services, is also located northwest of the Rogue Valley Mall.

“Even the service providers don’t know what services are available,” says Tinnin. What advocates want is a centralized location for services to ensure decisions are effectively and efficiently provided. Jackson County Continuum of Care (CoC), a U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development-mandated effort to end homeless that allocates around $300,000 a year to local service providers fighting houslessness, dedicates staff time to maintaining a “coordinated entry system” designed to serve this very role. For some, the results have not been satisfactory.

“It’s a good idea in theory,’’ says Ferrell, who is also a board member and Vice-Chair of the CoC. Even though Maslow Project is one of the main users of the coordinated entry system, no one at Maslow has been part of conversations to move people seeking housing off the system into housing. She does not know who makes these decisions or whether the people who get housing are taken off the list.

Constance Wilkerson, Manager at CoC, says that of the 24 local service providers currently using the system, the extent to which they use the system varies widely. “It’s up to the particular agency how they are going to utilize it,” she noted. If a system like this is only updated by some service providers, expediency and efficiency suffer.

Collective action is needed, and coordination and transparency are essential for expediently and efficiently providing services.

We were robbed

What if a centralized area where service providers could offer a one-stop-shop for people seeking housing, medical treatment, food, hygiene, mail services, financial services, internet, and computer access, phone chargers, and other resources? Maig Tinnin excitedly points to the possibility of a centrally-located space, like the Rogue Disposal & Recycling building – the bottom floor of which the City of Medford owns – where people could be connected to services and service providers could harmonize efforts. Expedient, efficient, central.

Medford was two Democrats away – one in the Oregon House and Senate – from receiving $2.5 million of state funding for a navigation center. According to Representative Pam Marsh, this money was slated to come from a $40 million investment to address houselessness throughout the state, ten times more money than has been allocated years past.

By exploiting an archaic rule that requires at least two-thirds of state legislators to be present for a vote, Republicans, including Medford’s current State Representative, Kim Wallan, fled the legislature to kill a climate bill.

By fleeing the legislature, Wallan killed 117 other bills, multiple of which would have allocated millions of dollars to Medford’s most vulnerable communities, via a navigation center and desperately needed services. She walked out on the houseless community. Our community and our state lost out.

Where are we now?

Along the Greenway, dwellings are nestled amidst lush brush and brambles. A Styrofoam cup protrudes from the tall grass. Residents still traverse the riverbank on foot and bike. The place is referred to as Paradise.

Throughout the pandemic, the houseless population has been less frequently displaced. This is because those with political capital believe displacing them may spread COVID-19 – simultaneously an acknowledgment of the unsanitary and dangerous conditions of poverty and paralysis of what to do about it.

Chief Clauson and other law enforcement officials signal a desire to return to more frequent sweeps to “clean up” the Greenway. Yet, cleaning up the Greenway for the “good of the community” by displacing houseless people only fuels environmental hazards and perpetuates chronic houselessness.

Uprooting peaceful people who have nowhere to go merely increases environmental hazards and gives them less bandwidth to seek housing and other services. Until the scarcity of resources, particularly transitional, affordable, and addictions-recovery housing, is addressed, the houseless community will need to live along the Greenway. There is nowhere else to go.

Medford City Council recently passed a 25-tent temporary campground resolution, citing MPD and Medford Fire Department’s urgency to clear encampments in time for fire season. Whether the temporary campground will expand or exist past the September 30, 2020 sunset date is unclear. The service provision teams coordinated by Emergency Operations Center Operational Group Leader Steve Lambert are being dissolved in favor of providing services at the temporary campground, located near Biddle and Midway Roads.

According to a July 20 flyer released by the Jackson County Homeless Task Force, a subcommittee of the CoC, “Daily meal deliveries along the Greenway will stop, and toilets/handwashing stations will be removed from the Greenway beginning Monday, July 27.”

Only residents of the temporary campground will be provided with food, hygiene, and medical services.

The insufficiency of these services may be unconstitutional. In a recent court case, the U.S. District Court in Medford ruled that in light of Grants Pass’ scarce transitional housing stock, City laws banning people from camping on publicly-owned property are a violation of the “cruel and unusual punishment” clause of the US Constitution’s Eighth Amendment. The ruling cites current COVID-19 guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that recommends encampments should not be cleared unless housing units are available.

Medford’s brimming shelters and 25 additional, but temporary, tent sites cannot hold the people scattered through approximately 150 camps along the Greenway. Thus, most people along the Greenway will be left without basic resources in the midst of a raging pandemic.

Furthermore, the temporary car camping lot that Maslow has been operating during the pandemic is shutting down at the end of the month and St. Vincent De Paul, which generally serves over a hundred meals daily to houseless people, is closed due to a COVID-19 outbreak.

Whether the campground will attract many residents living along the Greenway is unclear. The campground is currently slated to be monitored by two law enforcement personnel around the clock. No plan exists to include residents in decision-making processes or support peer-to-peer mentoring, which would build belonging, support houseless community leaders, and reduce tensions between residents and law enforcement.

In addition to being left out of campground discussions, houseless residents were neither asked to help create a plan for sheltering in place along the Greenway nor provide feedback about city, county, or service provider efforts to serve their needs. If these services are actually for the houseless community, providers must honor self-determination and work from a place of collaboration, not coercion. By neglecting to bring these voices into these conversations, law enforcement, government officials, and service providers deepen the hierarchies that fuel systemic inequality.

Some are worried that the temporary campground means the resumption of camping and trespassing tickets. Pickles told me that officer Randy Jewell said when the campground opens, “…there will be no more camping on the Greenway.” “So, back to the cat and mouse game with nowhere to go,” she lamented.

If sweeps resume after the temporary campground is established, and the temporary campground holds so few people, how can law enforcement and government officials say that the camp is anything more than a ploy to continue displacing houseless people? In the midst of the pandemic, how are these people supposed to meet their basic needs while respecting public health guidelines?

None of this happens in a vacuum. In the U.S., houseless communities lack the political and economic capital necessary to demand that they be treated like humans. Decisions about their livelihoods are made without their consent. To have property is to have a political and economic stake in the eyes of local government, and to have these things is to have a voice.

To make matters worse, state and local community leaders expect a new wave of houselessness when the eviction and foreclosure moratorium ends on September 30, 2020. Already, nearly 51 million U.S. households do not make enough “…to survive in the modern economy,” according to a report by the United Way. Month to month, citizens cannot cover basic needs such as housing, food, and health care.

Pam Marsh, Chad McComas, Kevin Stine, and Maig Tinnin are gravely concerned about how cash-strapped governments and non-profit service providers will respond to increased demand for already-scare services. Marsh notes that the state has given “crumbs” to services that help address houselessness, and that the pandemic-induced recession will make sufficiently funding such services difficult in the immediate future. And it looms.

In the midst of the chaos, advocates center and push for local solutions, like a continued moratorium on ticketing people for camping along the Greenway, a navigation center, leadership from houseless residents on all decisions relating to the houseless community, and programs to provide services and crisis intervention without law enforcement. To dismantle conditions that lead to chronic houselessness in our community, those with property and political and economic power must stand with their houseless neighbors to demand just treatment.

Sam Becker is a Counterbound co-founder, editor, and policy wonk from Talent.