By Herbert Rothschild for Ashland.news

One of the ways that U.S. Quakers take our commitments to peace and justice into the public forum is through the Friends Committee on National Legislation. Founded in 1943 and headquartered in Washington, FCNL lobbies Congress directly and through a grassroots network of Quaker congregations and advocacy teams. Each year it hosts a three-day Spring Lobby Weekend, during which the roughly 400 young adults who attend learn about lobbying and a particular piece of legislation for which they then advocate at the offices of their members of Congress.

In 2023 and 2024, the Quaker Meeting in Ashland and the Rogue Valley Advocacy Team sponsored two Southern Oregon University students to attend Spring Lobby Weekend. Cameron Aalto, who went in 2023, is currently interning for Ashland.news; his byline recently has appeared above a number of highly accomplished news stories. Connor Babbitt, who attended this year, is the student representative on the Ashland.news board.

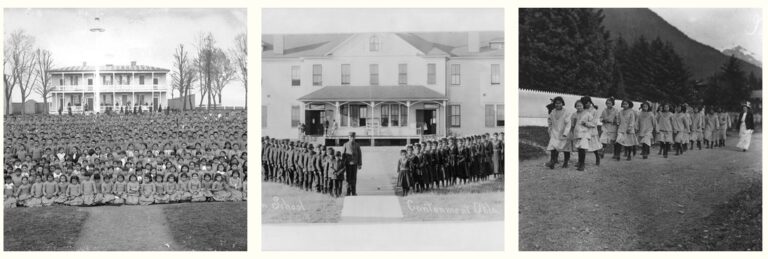

This year’s legislative focus for Spring Lobby Weekend, the one for which Connor advocated, was a bill to establish a Truth and Healing Commission on Indian Boarding School Policies in the United States. Numbered S. 1723 in the Senate and H.R. 7227 in the House, the commission it would establish would investigate the impacts and ongoing effects of the Indian Boarding School Policies, under which American Indian, Alaska Native and Native Hawaiian children were forcibly removed from their family homes and placed in boarding schools.

A Truth and Healing Commission will:

- Formally investigate and document the assimilation practices and human rights violations that occurred against Native Americans, Alaska Natives, and Native Hawaiians.

- Hold culturally respectful and meaningful public hearings for victims, survivors, and their families to testify on the impacts of these policies.

- Be guided by a Truth and Healing Advisory Committee with representatives from tribal organizations, tribal nations, experts, and survivors.

- Develop a final report with recommendations for the federal government due no later than five years after enactment on policies and commitments to address the impacts of Indian Boarding School Policies

The reality this legislation addresses is a gruesome one, and not so distant in time as one would like to think. Between 1819 and 1969, the U.S. ran or supported 408 boarding schools designed to eradicate Native American identity. The Canadian government established similar schools with the same intent. On its website, the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition, a nonprofit formed to advocate on behalf of Native peoples affected by U.S. Indian boarding school policies, has an interactive map of the locations of those schools. There were several in Oregon. The closest to us was the Klamath Indian School in Chiloquin, which operated from 1875 to 1927.

David Wallace Adams, professor emeritus of history and education at Cleveland State University, concluded from his research that by 1926, nearly 83% percent of American Indian and Alaska Native school-age children were enrolled in Indian boarding schools in the U.S. The Rev. Jim Bear Jacobs, a member of the Stockbridge-Munsee Mohican Nation and director of community engagement and racial justice for the Minnesota Council of Churches in Minneapolis, asserts that “every Native person alive today is no more than three generations removed from a direct ancestor being in boarding school.”

Children as young as 3 years old were forcibly removed from their homes and sent to schools, some of them hundreds of miles away. Parents who resisted their removal or failed to comply with the harsh no-contact policy were incarcerated or lost access to food rations and clothing from the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

Once at the schools, the children were forbidden to use their native languages or preserve their native appearances. Routinely, violations were enforced with brutal corporal punishments. In addition to the physical, sexual, psychological and spiritual abuse they suffered in the schools, many residents were sent in the summers to non-Native homes and businesses to perform involuntary and unpaid manual labor.

Brig. Gen. Richard Henry Pratt, who founded and then ran the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, stated that the ethos of Indian Boarding School Policies was to “kill the Indian in him, and save the man.” In fact, the process often killed both. At least 189 students were buried in the Carlisle Indian Industrial School’s cemetery.

In that regard the Carlyle school wasn’t unique. Thousands of the children who were forced into the schools were never heard from again. A report released by the U.S. Department of the Interior in 2022 said that marked or unmarked burial sites have been found at 53 of the schools, including the Chemawa Indian School in Salem, Oregon. If a Truth and Healing Commission is established, one of its mandates will be to preserve the burial sites and, when possible, to repatriate the remains to the appropriate tribes.

About one-third of the schools were owned and run by church institutions. Of the 14 denominations that ran schools, Roman Catholic religious orders ran at least 84. They could be as abusive as the government schools. At a hearing that Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland conducted in Seattle, a Sicangu Lakota man displayed replicas of the rope, belt and leather straps with which he was beaten at the St. Francis Indian School in South Dakota.

Haaland is a member of the Pueblo of Laguna. She introduced the bill to formally confront this shameful legacy when she served as a freshman representative in the 117th session (2019-20) of Congress. After Biden appointed her secretary of the Interior, Haaland held hearings across the country, offering opportunities to Native peoples to share their stories of suffering and intergenerational trauma.

Often, she opened a session with these brief remarks: “I will listen to you. I will grieve with you, I will weep, I will feel your pain. As we mourn what we have lost, please know that we still have so much to gain. The healing that can help our communities will not be done overnight, but it will be done. This is one step among many that we will take to strengthen and rebuild the bonds of the Native communities that the federal Indian boarding schools set out to break.”

Oregon Sens. Jeff Merkley and Ron Wyden are co-sponsors of S. 1723. Perhaps Rep. Cliff Bentz can be induced to co-sponsor H.R. 7227.

Herbert Rothschild’s columns appear on Friday in Ashland.news. Email Rothschild at herbertrothschild6839@gmail.com

In August 2023, NABS released its latest research identifying 523 Indian boarding schools in the United States. This three-year project resulted in the largest known list of U.S. Indian boarding schools ever compiled to date.

Editor’s note: The Quakers, also known as the Friends, ran more than 30 Indian boarding schools. The group has created a ministry titled, “Towards Right Relationships with Native People. See related article: Quakers Grapple with Legacy of Indian Boarding Schools

Quakers ran more than 30 Indian boarding schools. The students faced cruel practices of child labor, forced assimilation, and physical punishments. In an 1869 letter, Friend Edward Shaw from Richmond, Indiana, wrote that Quakers participated “to protect, to Civilize, and to Christianize our Red Brethren.”

Paula Palmer, who founded the Quaker ministry, Towards Right Relationships with Native People (see https://friendspeaceteams.org/trr/), wrote in Friends Journal that Quakers were some of the staunchest proponents of cultural genocide. They advocated fully removing children from their families, believing “the whole character of the Indian must be changed.”