Workshops, movement strategies and and collective empowerment through the Highlander Folk School

The movement for racial equality for Black Americans has taken many forms, including integrated grassroots movements backed by popular education models and collective empowerment. These efforts led to incredible victories in overcoming segregation and Jim Crow laws in the South and leading to effective strategies that resulted in the 1964 Civil Rights Act and other landmark legislation.

One center for training and coordination included the Highlander Folk School in Tennessee. Now known as the Highlander Research and Education Center, the school was founded in 1932 during the Great Depression as an education center for workers in support of union organizing. Co-founders Myles Falls Horton and Don West began hosting interracial workshops in support of the growing civil rights movement 1950.

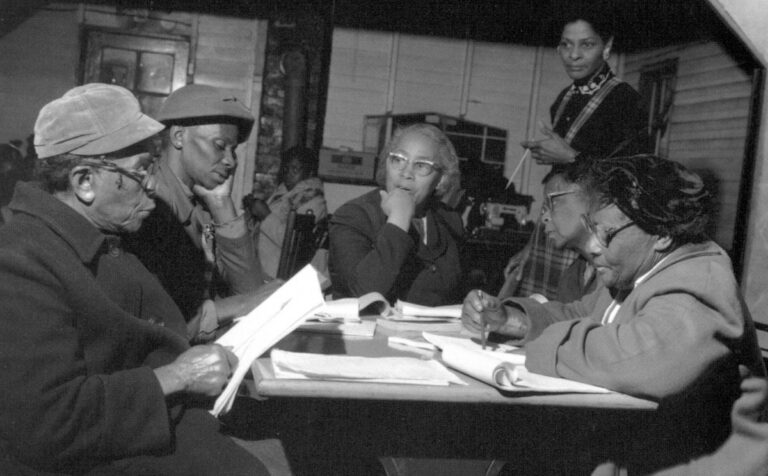

In the years to come, the Highlander Folk School served as an educational and strategy hub for Black educators, ministers, and leaders. The literacy and legal training components became central to supporting voter registration in the South after the group launched a Citizenship Training School, to be led by the revered Septima Poinsette Clark. The program not only educated many people on their legal rights as Black Citizens, but also included an intensive literacy program to counter the oppressive “literacy requirements” that served as barriers for voter registration in eleven states.

Septima Clark, a longtime educator in South Carolina, was known to be called the “mother of the movement” by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. In 1953 she lost her job and pension after defying a racist law that demanded she abandon her role at the South Carolina NAACP if she wanted to continue teaching. After losing her job in public education, Myles Horton was quick to hire Ms. Clark as the director of Highland’s new Citizen Training Program. The program is credited with supporting voter registration campaigns across the South and continued to carry forward its vision beginning through the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC).

“I believe unconditionally in the ability of people to respond when they are told the truth. We need to be taught to study rather than believe, to inquire rather than to affirm.”

Septima Poinsette Clark

Myles Horton, the union organizer and trainer who worked with Dr. MLK Jr, Rosa Parks, Septima Clark and many other esteemed civil rights leaders at Highlander, prioritized the discussion of peoples’ lived experiences of oppression and visions for a better world. He would often decry that people must take risks and push their personal boundaries to make change.

“Now I’ve been criticized for advocating that people push their boundaries because sometimes people get caught. Sometimes people get fired,” said Horton in 1957. “Sometimes people lose their jobs because of pushing the boundaries too far, but it’s an interesting experience. Once people find they can survive outside the limits, they’re much happier.”

Horton would later find out for himself that pushing those boundaries can take a material effect. In the 1950s in Tennessee, white segregationists were angered by Highlander’s interracial programs and a advocacy for racial justice. The groups attempted to label the popular education model as a communist training facility, and Septima Clark was arrested on phony charges of illegal possession of whiskey. After the charges were dropped, the State still revoked Highlander’s charter, seized the land and Horton was forced to reopen at a new location under a new name.

During the upheaval, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference took over the managament of the Citizenship Education Program and expanded it. In an interview in 1964, Ms. Clark reported:

“I stayed at the Highlander Folk School for seven years working with adults. It was there that I was able to develop the program called the Citizenship Education Program which is now [1964] in the eleven southern states and we have at this moment 595 teachers and around 29,000 students who are registered to vote.”