by James Phillips

In case you missed it, a recent news item tells us something significant about the uses of violence for “national security,” no matter what the cost in human lives and misery in Latin America and elsewhere. Not a pretty story, but true and important.

What Was He Thinking?!

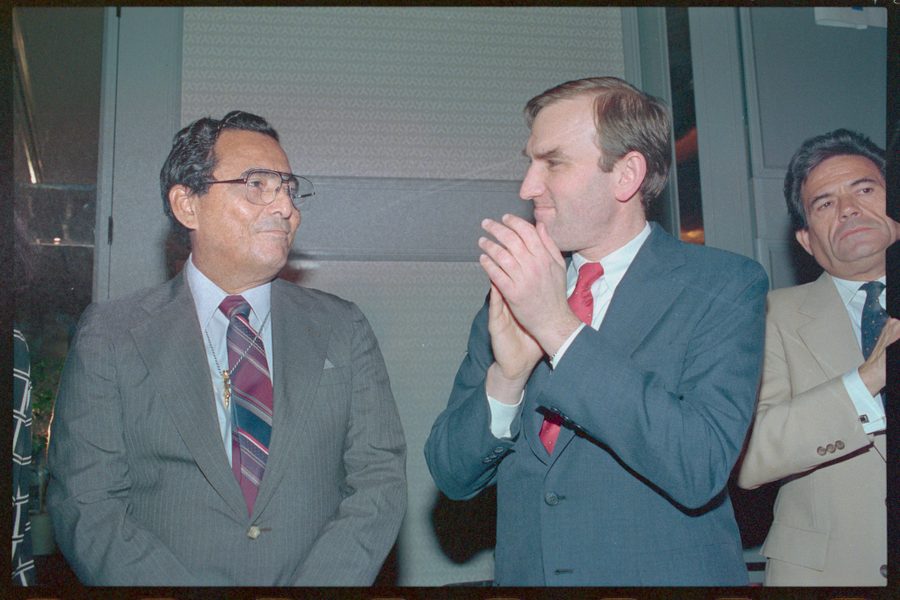

Last week, President Biden indicated his intention to nominate Elliott Abrams to a position on the State Department’s Advisory Commission on Public Diplomacy. According to its website, the Commission’s work is “appraising U.S. government activities intended to understand, inform, and influence foreign publics and to increase the understanding of, and support for, these same activities.” What this neutral sounding language means in practice is whatever it takes to extend and maintain U.S. control of other countries. The activities of Elliott Abrams over the past forty years provide some of the worst examples of this mission, and of a blatant disregard for the sovereignty, rights, and lives of others.

Mr. Abrams is a known commodity. His entire career in government has been guided by his apparent belief that the killing, torture, and misery of any number of Latin Americans (and others) is justified in the name of protecting the “security’ of the United States. This is the essence of the so-called National Security Doctrine that was employed by all of the violent military dictatorships of Latin America in the 1970s and 1980s. It was and remains very much a central part of the thinking of many in the U.S. government, such as Mr. Abrams. The “security” justification in this context was and is a lie, an excuse for eliminating all dissent and extending control over a population. I saw firsthand the results of some of Mr. Abrams efforts on behalf of U.S. “security” in Central America in the 1980s. I fear for what he might be able to do again if he holds any position in the U.S. government.

In the early 1980s, Elliott Abrams was Assistant Secretary of State for Inter-American Affairs in the Reagan Administration. He was involved in conceptualizing, organizing, and white-washing policies and practices that cut a broad path of murder, mayhem, and misery in Central America and are still haunting and shaping the region today, in large part because the architects of the terror, like Mr. Abrams, are still in positions of influence in Washington and in the region. As one Honduran woman told me after the 2009 coup in her country, “these same guys that caused so much misery in the 1980s are still walking the streets freely right now.”

Guatemala

In the early 1980s, under the guise of “counter-insurgency,” the Guatemalan military systematically raided some four hundred Mayan Indian villages, killing men, women, and children. Estimates of the dead ranged from fifty to two hundred thousand. Because the authors of this genocide remained in power, it took decades to bring anyone to justice for this atrocity. Neither President Reagan nor Mr. Abrams did anything to stop the genocide or to assist in bringing the perpetrators to justice. By 1984, much of the Guatemalan countryside was organized by the military into rigidly controlled communities where people were forcibly formed into safety patrols and encouraged to spy on their neighbors or themselves risk death. Despite a few critical voices in the U.S. Congress and widespread international condemnation, the U.S. under Reagan, and with Abrams, continued to support and applaud the genocidal Guatemalan military and government.

El Salvador

In El Salvador, during the decade of the 1980s, the country’s military engaged in a long and brutal series of assassinations and massacres, with the excuse of guarding the nation against the “communist” insurgency of the Farabundo Marti National Liberation Front (FMLN). Perhaps the most infamous example occurred in the community of El Mozote, where the Salvadoran military massacred innocent people for allegedly aiding the FMLN. The government and the military adopted the assassination tool that came to be known as the “death squad,” (esquadron de la muerte), that was widely used also in Honduras and Guatemala.

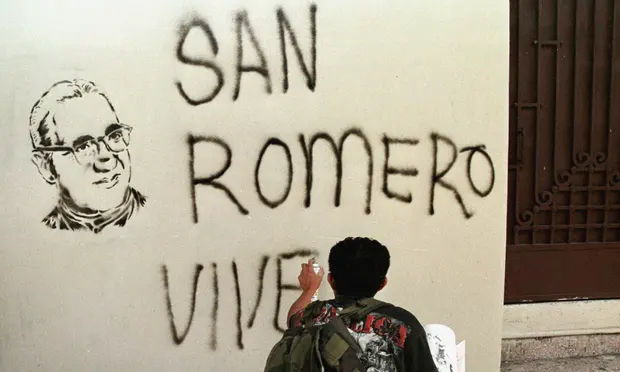

The Salvadoran military, with the excuse of rooting out “communism,” also targeted the progressive sectors of the Catholic Church. In 1979 and 1980, the military assassinated several priests and Catholic lay leaders. In March 1980, a military death squad shot and killed Archbishop Oscar Romero as he said Mass in the chapel of a hospital in San Salvador. In December of that year, a death squad killed four U.S. citizens—three nuns and a Catholic lay worker—as they were driving on a road coming from the airport. And on the night of November 16, 1987, a military death squad enter the living compound of six Jesuit university professors and administrators at the University of Central America, dragged them out of their sleep, and shot them in the courtyard. They also killed the housekeeper and her teenage daughter. It was said that the Salvadoran military trained to the chant of, “Be a patriot, kill a priest.” The military also had a practice of entering university classrooms to drag out students or professors deemed subversive or communist. Often, their bodies were later found dumped somewhere.

As thousands of Salvadorans tried to flee the violence by crossing the Sumpul River into Honduras, Salvadoran military detachments pursued them, shooting at and killing many as they tried to swim across the river. The military even hunted them into Honduras, where the Honduran military did little to protect the fleeing Salvadorans, some of whom found shelter and temporary protection among poor Honduran peasants.

At this time, El Salvador was the third largest recipient of U.S. military and economic aid (behind only Israel and Egypt). U.S. Representative Joe Moakley (D-MA) led a Congressional fact-finding delegation and issued a report that was a scathing denunciation of the use of U.S. aid for the Salvadoran military that was engaged in such human rights disasters. This was one of a series of challenges against the Reagan narrative about Central America. Fortunately for Reagan—and unfortunately for the people of Central America and the U.S.—one of Elliott Abrams’ “talents” was damage control—spinning the story so as to justify the violence and downplay any narrative to the contrary. This service was enormously important for the Reagan death train in the 1980s, and it remains just as important today.

Honduras

Honduras became the center of U.S. military presence in the region. In 1981, as the Reagan Administration was coming to power in Washington, a Honduran military dictatorship was returning the government to a weak civilian presidency, but the army retained actual control of the country under General Gustavo Alvarez. The Reagan Administration worked to make Honduras its most reliable colony and the platform for U.S. intervention and control of the region. The U.S. military expanded its presence in the country and its close working relationship with the Honduran military. The U.S. Embassy and a group of wealthy Hondurans sent the civilian president a set of economic policies to adopt, including the opening of the country for foreign extractive industries with little regulation. This set of policies was not a suggestion but a demand. It favored wealthy investors, corporations, and the powerful at the expense of the poor. Critics sarcastically called it, “Reaganomics for Honduras.”

What followed was what many Hondurans today recall as one of the worst periods of political repression in the country’s history. [I was in the country for part of this time.] Student activists, labor leaders, and others were “disappeared” and often found dead and mutilated. Military roadblocks were everywhere, soldiers checking everyone riding on public transportation. Young men were systematically rounded up and jailed, disappeared, or forced into the Honduran military. The Honduran Army’s Battalion 316 became notorious as a death squad to assassinate leading critics of the U.S. or of the neoliberal economy the government was developing. Under pressure from the Reagan Administration, the Honduran government and the army allowed the south of the country, along the Nicaraguan border, to be turned into a safe zone where U.S. trainers, supplies, and advisers were funneled to Contra camps, and where Contra officers recruited young men among the Nicaraguan refugees in the large refugee camp near Jacaleapa.

By 1986, General Alvarez was in exile, and some of the worst of his national security policies had been at least slightly reduced, but Honduras remained the reliable outpost of U.S. influence and intervention in Central America, despite large and sustained protests among the Honduran people and the work of human rights and popular organizations in the country. The Honduran government was not always comfortable with the U.S. using the country as the staging point for war against Honduras’ neighbors, especially Nicaragua. When the Nicaraguan army chased some Contra forces out of northern Nicaragua and back into Honduras, the U.S. government spread the story that Nicaragua was invading Honduras. News reporters found Honduran President Azcona on a short holiday on the Caribbean Coast in northern Honduras. When asked why he was on holiday while his country was being invaded, he replied, “What invasion? There is no invasion.”

Abrams was adept at peddling fear as a weapon, and one of his contributions to this situation, along with supporting the application of the National Security Doctrine, was to encourage the idea (lie) that Sandinista Nicaragua was preparing to invade Honduras and turn it into a communist dictatorship. In Honduras, I could not find many people who really believed this. In neighboring Nicaragua, however, everyone lived with the fear that the United States would invade Nicaragua at any moment.

Nicaragua

Elliott Abrams was a busy man. But perhaps his most glaring “achievement” was his instrumental assistance in organizing, funding, and sustaining the Contra War in Nicaragua. There are many books about the Contra War covering a range of perspectives and formats, from large geopolitical studies to personal journals.

Under the Reagan Administration, Abrams was one of the chief architects of the Contra War in which the United States used legal and illegal means—including the so-called Iran-Contra Affair, and collusion with gangs and drug traffickers—to fund, arm, train, and advise the Nicaraguan Contra forces to destroy the Sandinista-led popular revolution. In 1979, that revolution had finally toppled the 45-year dictatorship of the Somoza family that had brutally ruled Nicaragua with the blessing of eleven U.S. Administrations from Franklin Roosevelt to Jimmy Carter. By 1981, Reagan and his posse were determined to topple the revolution. Abrams lent his skills enthusiastically to this effort.

The Iran-Contra Affair shows how far-reaching and cynical were the efforts of people like Mr. Abrams in the name of “security,’ but with the aim of maintaining U.S. imperial reach. The deal involved circumventing the law and restrictions placed on aiding the Contras who were trying to overthrow the Sandinista revolutionary government. Members of the Administration secretly brokered a deal to sell weapons to the Islamic revolutionary government of Iran, the same government that Reagan was publicly denouncing as an evil and repressive regime seeking to destabilize the Middle East. The money from the sale of these arms was then used to fund the equipping, training, and support of the emerging Contra forces on the border between Honduras and Nicaragua.

The hypocrisy and blatant illegality of this deal astounded and confused many when it was discovered. Some also pointed out that the deal undermined the authority of the U.S. Congress. Several of the central agents, including Abrams, were questioned by at least one Congressional committee, to which they lied. Abrams was among those convicted of lying to Congress but he got off with minimal punishment, and his career was soon resuscitated. He returned to formal and informal positions in several succeeding Administrations.

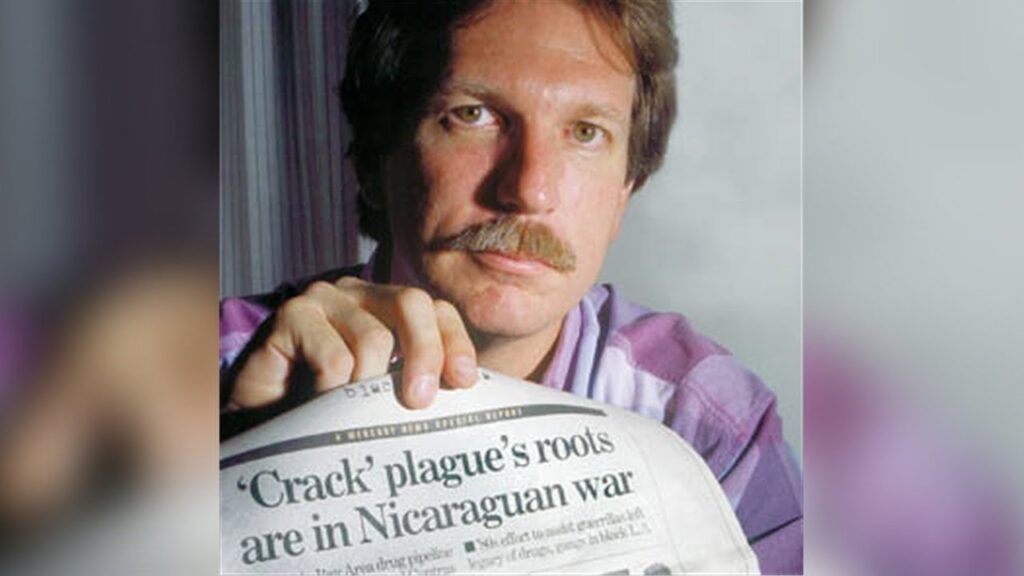

In addition to the Iran-Contra deal, the proponents of the Contra War found other ways to fund the war that were likewise both secret (for a time) and illegal, and that caused misery far beyond the borders of Nicaragua. In August 1996, Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Gary Webb stunned the world with a series of articles in the San Jose Mercury News reporting the results of his year-long investigation into the roots of the crack cocaine epidemic in the United States, specifically in Los Angeles.

The series, entitled “Dark Alliance,” revealed that for the better part of the 1980s a Bay Area drug ring sold tons of cocaine to Los Angeles street gangs and funneled millions in drug profits to the CIA-backed Nicaraguan Contras. This arrangement helped to destroy the lives of people in Los Angeles neighborhoods and the lives of Nicaraguan peasants thousands of miles away. A Justice Department investigation confirmed much of Webb’s findings. Various interests were involved in continuing this deal, and Webb was threatened by them and eventually forced into silence. He later died under circumstances that some found suspicious. This episode was told again in a feature length motion film titled Kill the Messenger released in 2014.

The strategy of the Nicaraguan Contras was shaped and directed by Abrams and others who referred to it as “low-intensity conflict.” It was anything but low-intensity for the Nicaraguan people who lived through the nightmare. The strategy was to target not the Nicaraguan Sandinista army but rather the civilian population, especially the small farmers and peasants in hundreds of rural communities throughout the country; to make life unbearable so that the people would turn against the Sandinista government or be unable to support it.

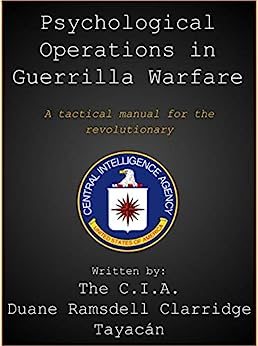

The CIA wrote and distributed to Contra soldiers and others a how-to manual for performing acts of sabotage against daily life and especially anything that was related to the Nicaraguan government, and included extensive discussion of how to conduct “psychological operations” to terrorize or convince the Nicaraguan population. CIA Director William Casey defended the manual as an “educational” tool.

A shortened and illustrated version was reproduced for distribution directly to Contra troops. When Nicaragua brought a case against the U.S. in the World Court in 1984, the manual was one piece of the evidence against the Reagan Administration. The World Court directed the U.S. to pay Nicaragua for damages caused by the war, but the Reagan Administration ignored the Court.

Witnessing the Contra War

My wife and I lived in Nicaragua in the mid-1980s during the height of the Contra War. I can personally testify to some of the horrors Abrams and others supported there. We spent eighteen months with the Witness for Peace ecumenical team, documenting the effects of Mr. Reagan’s and Mr. Abrams’ Contra War against the small rural farming communities of northern Nicaragua. Quite literally, it would take volumes to detail the landscape of death, destruction, torture, destroyed livelihoods, uprooted communities, and crushed hopes that we and others observed and documented as we tried to accompany Nicaraguans in this nightmare. There are many thoughtful descriptions in print, and they are not reading for the faint-hearted. Here, I can provide two out of hundreds of examples of what I personally witnessed in Nicaragua during Mr. Abrams’ Contra War. Putting aside all of the bureaucratic and political rhetoric of the instigators in far-away Washington, this is what the Contra War was like for so many Nicaraguan communities.

This description is taken verbatim from my field notes and journals. It is disturbing reading.

“The region known as Miraflores is a collection of sixteen small cooperative peasant communities in the mountains to the East of the city of Estelí. Each community has an average of about ten to fifteen families. The people are potato farmers. Almost all of them were displaced from other communities by Contra soldiers who attacked and destroyed their original villages. Contra forces have attacked these communities various times in the past couple of years.

On July 12, 1984, Contra soldiers attacked a community, burned some buildings, and killed Benjamin Talavera, a 22-year-old farmer. On June 4, 1985, Contras attacked another community in Miraflores, killing Martin Rodriguez, 20, Martin Diaz, 19, and Aristo Barreda, 19, all peasant farmers. They burned the truck of a local journalist who happened to be in the area writing a feature on the community. On January 5, 1986, Contra forces ambushed a truck from the Ministry of Agrarian Reform in another Miraflores community. Using mortars and hand grenades (supplied by the U.S.) they killed the 22-year-old truck driver, and a Nicaraguan army officer, Francisco Tercero.

At 7 p.m. on the night of May 20, 1986, Contra forces attacked the two Miraflores communities of Sandino (fifteen families) and Teodosio Prsvia (twelve families). The Pravia community had only recently built cinder block houses to replace their temporary wooden shacks, and the building was still incomplete. A small group of Nicaraguan army soldiers and local men held off the full Contra attack until most of the women and children could flee up the hill on a path in the dark to the neighboring community of Sandino. The Contra forces swept into Pravia, capturing one woman and holding her as a human shield. They burned to ashes almost a dozen wooden houses, two storage sheds full of seed potatoes, and the schoolhouse.

Then they turned their attention to the Sandino community. They attacked with mortars and grenades, shooting and looting houses. Hermida Talavera, 12, and her brother Rafael, 10, were in the house of their cousin Jesus, 15, when a mortar shell struck the roof. It is uncertain whether the three children were killed by the bursting shell, the collapse of the roof, or the grenade that a Contra soldier threw into the house. When I visited the scene a few days later, I saw the blood of the three children splattered on the wall of the house.

Silivio Chavarria, a Ministry of Agrarian Reform worker with a wife and children in Estelí, happened to be in the Sandino community that night after he and his work partner, Julio, had spent the day working with the people. A Contra soldier threw a grenade that injured Silvio’s leg so he could not move. After the attack, his badly mutilated body was found. Some people said they heard screams that night and thought he might have been tortured. When I visited Julio a few days later in Estelí, he recounted these details about Silvio. Julio himself was injured, his leg bandaged.

The Contras also killed Marta Tinoco, 21, a Nicaraguan Army soldier and daughter of peasant farmers, and they destroyed the communications radio she was using to call for help. They killed a Nicaraguan army lieutenant, Marco Cascante, and two Ministry of Housing workers who were in the community helping to build houses—Juan Francisco Lumbi and Concepcion Lopez Vargas. In all, eight were killed, including six civilians, three of whom were children. Sixteen others in the communities were injured, and more might have been killed if they had not managed to escape into the forest in the dark.

The Contra forces also destroyed or damaged at least fourteen houses, three storehouses, several thousand pounds of seed potatoes, a schoolhouse, and three trucks belonging to the Ministry of Housing.They slaughtered animals belonging to community members, looted personal belongings and small personal savings, and took an estimated ten thousand dollars (seven million cordobas) the Sandino community had gotten from the sale of potatoes.

When I visited May 26—the first “safe” day to be in the area—it was a scene of bizarre devastation. Bullet holes, blood, dead animals. In the mud beside a path was a basket of eggs. A picture of the Virgin Mary was propped up against a wooden post outside the blood-stained wall of a destroyed house. People said a Contra soldier carefully removed the picture before he shot up and grenaded the house.

Officials at the U.S. Embassy in Managua have been searching for a way to rationalize this attack. They said in a statement that communities such as Sandino and Pravia are “militarized if not actually military targets.” Apparently seed potatoes are a threat to national security.”

Later in 1986, I accompanied a delegation of U.S.citizens to the small peasant community of Venecia where the people were all from other communities destroyed by the Contra. On this piece of land on a mountainside, they divided their time between growing coffee and keeping constant vigil against Contra attack. In the U.S. delegation that day was Charles Litkey, a retired U.S. Marine chaplain who had received the Medal of Honor for his bravery in Vietnam. He was concerned about what the U.S. might be doing in Nicaragua.

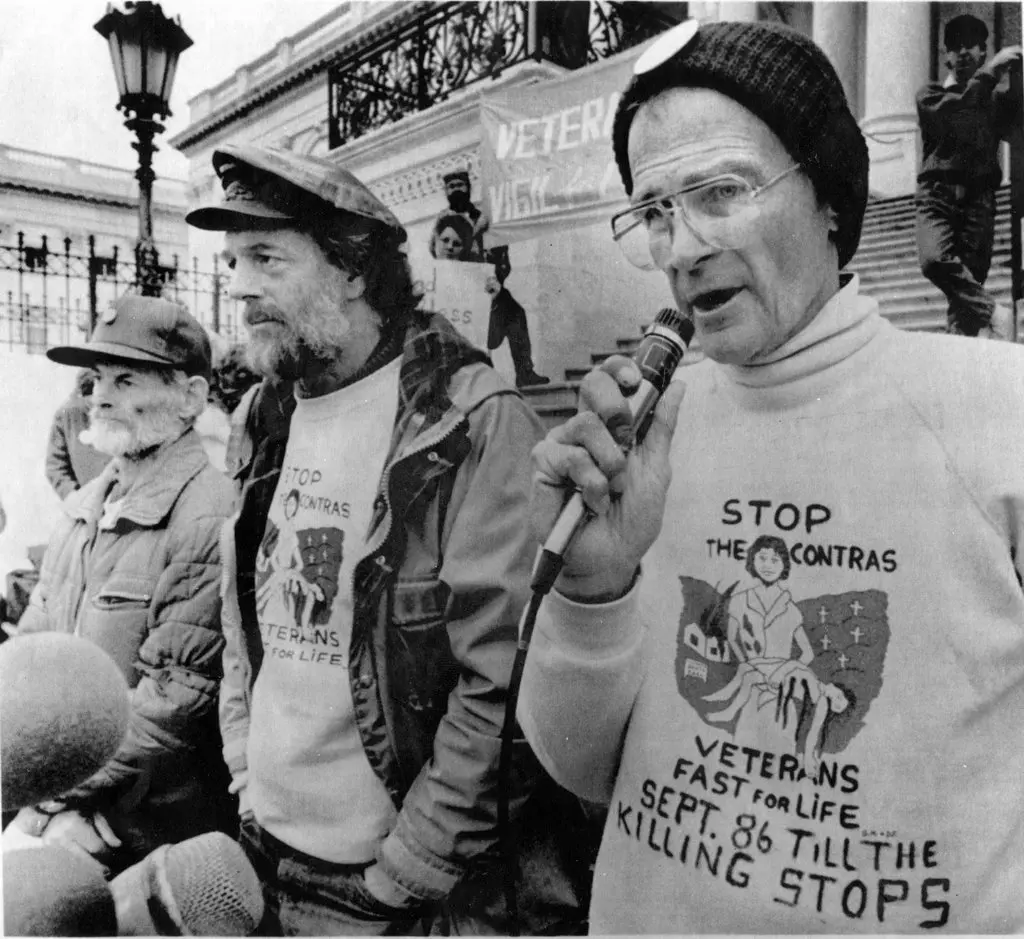

During the public sharing and discussion between the delegation and the people of Venecia, Doña Chepa, a woman who had already lost her husband and two sons from the Contras, walked up to Litkey, and said, “Please go home, put your hand on Mr. Reagan’s chest, and tell him to stop killing us.” Litkey cried. He went home, returned his Medal of Honor, and was one of four veterans who started a fast on the steps of the U.S. Capitol to stop Congress from funding the Contra War.

Doña Chepa might just as well have added Mr. Abrams to the people she wanted Litkey to confront. Abrams was central to the development and implementation of policies and plans that resulted in the suffering of these people.

Why This Matters Today, Now

Elliott Abrams’ appointment at this time to the State Department Advisory Commission on Public Policy is not a coincidence. Despite his past and recent efforts, and the enormous damage they caused, his work is not complete; the U.S. empire is not secure. The revolution continues in Nicaragua, and the Honduran people last year elected a new government. If successful, the new government will pose a threat to the established network of resource extraction, corruption, and repression that the U.S. has supported in Honduras since the coup of 2009. Abrams would be instrumental in the ongoing efforts to assure “regime change” in both countries—destroying the “danger of a good example” in Nicaragua and ensuring the continued colonization of Honduras.

Washington’s obsession with eliminating the Sandinistas and derailing the positive results of the 1979 revolution did not end with the formal close of the Contra War. The Sandinistas were defeated in the election of 1990, as the Contras continued to harass local communities and the Nicaraguan people. They got the message that the U.S. would not leave them in peace until the Sandinistas were out of power. Nicaragua endured a series of pro-U.S. neoliberal governments (1990-2006) during which most of the indices of poverty, poor health, infrastructure decay, and withdrawal of essential services increased, so that by 2006 Nicaraguans were ready to vote the Sandinistas back into power. Since then, the country has experienced continual improvements in many basic services, infrastructure, and conditions of daily life, despite heavy economic sanctions imposed by the U.S.

The fear that Sandinista-led Nicaragua could provide a positive example for the rest of the hemisphere has always haunted the leadership in Washington. Over the past two decades the U.S. and the CIA, through organizations with high-sounding names like the National Endowment for Democracy (NED), have supported internal opposition groups to undermine the Nicaraguan government.

An indispensable arm of this effort is the intense negative news and propaganda campaign that we are witnessing, in which Nicaragua is cast as a brutal dictatorship that represses human rights, religion, and all political expression. This media campaign makes ample use of distortions of fact, outright fabrications of “truth,” and erasure of any context that might allow us to evaluate events clearly. It has succeeded in dividing solidarity for Nicaragua and polarizing attitudes towards the Sandinista government in general, and Daniel Ortega in particular. Any action by the Nicaraguan government to respond to provocation is denounced as brutal or extreme. The Nicaraguan government’s measured response to the uprising of April 2018 was denounced in Washington and the mainstream media as extreme repression of a “peaceful uprising.” There is ample evidence to show that the opposition was anything but peaceful. There is an alternative narrative from eyewitnesses in Nicaragua that paints a very different picture of events, a narrative that the U.S. has tried very hard to suppress and keep out of the media.

Elliott Abrams’ special talents would lend themselves perfectly to this ongoing effort to undermine and remove Ortega and the Sandinistas from power, again as in the 1980s. Abrams is talented in forging efforts to thwart the will of a people and substitute the will of the U.S. government in its place—regime change and forms of intervention by any means, at any cost.

As for Honduras, the new government of Xiomara Castro is facing enormous dilemmas as it tries to repair the damage done to the country by its predecessor, and dismantle the entrenched web of corruption of the past decade. That corrupt government had the support of the United States. But the U.S. has issued veiled and more direct warnings to the Castro government. A campaign of increased violence and negative criticism is underway, and Castro is under enormous pressure to abandon most of her election promises of reform. Here also, Abrams would be in an excellent position to help further this pressure campaign and ensure that the Honduran government answers to the demands of U.S. economic interests rather than the needs of the Honduran people.

The larger issue in all of this is not any single person, even Elliott Abrams. It is the worldview, the mindset that prevails among those who direct our foreign policy. It is an imperial addiction. The same mindset that helped orchestrate the genocide in Guatemala, the murders of Church people in El Salvador, the death squads and militarized state in Honduras, and the Contra War in Nicaragua. That mindset is still infecting Washington. Some of its purveyors are still in place, shaping and effecting policy and practice. They reject the popular will, and instead support tighter control over the many, and more extraction of their resources. This is what passes for “national security.” A real step to security for the US and the hemisphere would be to bar people like Elliott Abrams from holding any office or responsibility in any level of government anywhere. The appointment of Mr. Abrams requires Senate approval. Maybe it is time to contact your Senator.