What does the Honduran Presidential Election of November 28 tell us?

by Dr. Jim Phillips

I was in Honduras from November 17 to December 13. During that time, Honduras held

general elections. The outcome of these elections is highly significant for Honduras and

the United States. Here is my initial report and interpretation. — Jim

El Progreso, Honduras, Friday, November 26, 2021

Driving through the narrow streets near the city center, we see lines of people: some elderly, some in wheelchairs, extending down city blocks and around corners. People waiting for banks to open so they can claim the bono (cash payment) that the incumbent government of President Juan Orlando Hernandez and his National Party are doling out two days before the presidential election. According to his many critics, this is one of the more blatant attempts by Hernandez and the National Party to buy votes to secure the election of their chosen successor, National Party candidate Nasry Asfura, said to be a close associate of Hernandez.

In the eight years of Hernandez’ presidency the poverty rate has grown to include 70 percent of the population, and the country ranks second poorest in the hemisphere. Critics say that, having created such poverty with a foreign- oriented extractive economy and rampant official corruption, Hernandez has instituted various programs to “assist” the poor, but in fact to turn the population into dependent clients of the government and the Party, and to buy the support of the poor majority.

San Pedro Sula, Saturday, November 27

This is the second-largest city in Honduras, and the commercial center of the country. I accompany some dear Honduran friends as they shop for food, water, and supplies. Long lines of shoppers rushing to secure supplies intended to last for several weeks or a month. I see online images of stores and businesses where workers are boarding windows in anticipation of violence.

Everyone seems concerned that there will be a repeat of the post-election violence that marred the last presidential election in 2017. It is widely believed by many Hondurans and international observers that Hernandez stole that election. Huge protests followed in the streets of cities, as the government’s military police forcefully attacked nonviolent protesters. At least 28 were killed, many were injured or suffered the effects of tear gas launched against them. When I arrived in Honduras in January, that year, more than six weeks after that election, the protests and the repression were still occurring almost daily.

So much of the concern and talk on this day before the 2021 election is about the potential for another “stolen” election, more protests and repression. Many are aware that, this time, the pent-up anger, frustration, and desperation of people might not be expressed as peacefully as before.

San Pedro Sula, Sunday, November 28

Election Day, at 8 a.m. I accompany my Honduran friends as they go to their polling places to vote. For reasons I don’t understand, husband and wife must go to different polling centers, both in schools. At both places, there are lines of cars and people, but the voting seems to go smoothly and rather quickly with no incidents to disrupt matters. Later, I will hear reports of incidents at a few polling places, but nothing that seems to significantly cast doubt about the legitimacy of the process. For the rest of the day, people anxiously await the returns.

By law, the National Electoral Council (CNE) must begin to release preliminary results at 8 p.m., three hours after the official closing of the polls. By 6 p.m. back in El Progreso, I listen to Radio Progreso’s election coverage. At 8, there is no preliminary announcement. At 8:45, the preliminary tally puts the opposition Libre Party candidate, Xiomara Castro, well ahead of National Party candidate Asfura. Good news, but too early for celebration. People remember the “stolen” election of 2017 when the opposition candidate seemed well ahead, only to have the incumbent Hernandez and the National Party claim a narrow victory three days later.

Tense waiting. I sit by my cell phone listening. At 11:15, the CNE announces that Castro’s lead has widened to almost 14 points. An hour later, as I lie in bed, the CNE declares Castro the apparent victor.

El Progreso, Monday November 29, 12:15 a.m.

From my bed, it sounds to me like the city of El Progreso has exploded into celebration. Fireworks, shouts, caravans of cars, horns blaring, people chattering in the streets. A collective sigh of relief?

This election has already gone differently than the last. Later that day, Castro’s lead holds, even increasing. People express surprise that her lead is wider than even many of her supporters hoped for. The CNE announces that the voter turnout was high. A few days later, we learned that nearly 70 percent of eligible voters cast ballots, the highest turnout in the country’s history. The youth vote was reported to be especially high. This alone is significant in a country where people have learned from bitter experience not to trust political institutions. But there is always hope.

Watching and Waiting. Over the next days, there was a sense of relief, caution, and concern. Xiomara Castro had won the presidency according to the official CNE count, but Hondurans had learned from experience that this is not enough. Over the next few days, National Party candidate Nasry Asfura conceded, and was shown on Honduran media visiting Castro to congratulate her. The third major candidate in the election, Liberal Party candidate Yani Rosenthal, also conceded and congratulated Castro. During the week, the CNE released figures showing that the final tally was likely to be fairly close to this: Castro, 51%; Asfura, 38%; Rosenthal, 8%; with the rest split among several small parties.

Later in the week following the elections, two more events occurred that allowed many Hondurans to breathe a bit more easily. Incumbent president Hernandez finally congratulated Castro, conceding the end of twelve years of National Party rule that had begun with a coup d’etat in 2009 in which Hernandez himself played a major part. People had wondered out loud if Hernandez might stage a last-minute maneuver to allow him, somehow, to remain in power. He may face criminal charges for drug trafficking in the U.S. once he leaves office; his brother is serving a long sentence in a U.S. prison for that. During his years in office, Hernandez lavished resources and attention on the Honduran military, often to the detriment of funding for public services like health and education, making the military personally answerable to him. These considerations caused some concern.

At this writing, the future of Juan Orlando Hernandez is still uncertain. He remains president until the inauguration of Castro in late January.

During the week after the election, the U.S. State Department issued a congratulatory statement recognizing Castro’s victory, and mentioning how the United States had always promoted democracy in Honduras—a statement not entirely in keeping with the experience of many Hondurans. The Embassy echoed this statement.

In Honduras, the endorsement of the U.S. Embassy and the State Department carry particular importance. A former Honduran Congressman once told me, “Everyone knows, this country is run by the U.S. Embassy.” A century of U.S. economic, political, and military intervention and dominance is the historical context here. It is widely believed that the Honduran military’s relationship with the new president will take its cue from Washington.

After these events, however, the watching and waiting continued, since the control of the new Honduran Congress was not yet determined. Castro’s Libre Party and its allies—the Salvador de Honduras Party and the Party of Innovation and Unity (PINU)—won control of the two largest cities, Tegucigalpa and San Pedro Sula, as well as other smaller cities and municipalities, but its ability to curb violence and corruption at the local level in many areas is far from certain. These are precisely areas where much of the land conflict, human rights violations, criminal enterprise, and forced displacement of communities occur. It seems that Castro’s Libre party and its allies—Salvador and PINU—will need support from Rosenthal’s Liberal Party to control the Congress.

The Liberals, along with the National Party, have formed the dominant two-party control of politics in Honduras for more than a century. As many Hondurans tell me, both of these parties have long represented the interests of large landowners, large businesses, and foreign corporations. But there is a moderate reformist tendency in sectors of the Liberal Party that have supported reform and moderation in the past, and may decide to support Castro. If enough do so, Castro’s allies may have enough numbers in the Congress to pass some of the many reforms and changes she is proposing. If nothing else, the election seems to have broken the grip of the two traditional parties on Honduran political institutions.

Glimpses into the Future?

President-elect Xiomara Castro issued a 30-point plan for her first period in office. This includes the rescinding of laws that facilitated official corruption and impunity, and laws that criminalized peaceful popular protest and the defense of human rights and local resources. She also intends to bring back the international anti-corruption unit that the Hernandez government and the outgoing Congress had undermined and forced out.

Castro will be the first woman in the history of Honduras to be elected president. She intends to pay special attention to the defense of women in Honduran society. The country currently bears one of the highest rates of femicide in the world, and violence against women is widespread.

The Economy Is Crucial. The most frequently heard concerns of Hondurans—both in this election and among those who have contemplated emigration over the past decade—have been the lack of decent, dignified employment; economic insecurity; and poverty. Poverty spawns a variety of other ills, including gangs, domestic violence, and attacks on the human rights of the poor.

The current model of economic development is based largely on the extraction of resources by foreign corporations, and remittances sent back to Honduras by Hondurans in the United States—approximately $ US 4 billion per year in the past few years, providing almost 20 percent of the Honduran economy. In this sense, emigration has been a lucrative business for the outgoing government during the past decade.

President-elect Castro proposes to change the current dominant model of economic development that relies on export expansion to a different model more reliant on import substitution (her words). This means de-emphasizing foreign investment in extractive industries, and instead providing more support for local and community enterprises run by and for Hondurans. The significance of this transition would be enormous. Some of the pieces of this transformation are already present and have been for a while.

Near Danlí, southern Honduras, Saturday, December 4

A long-time Honduran friend takes me to a farm outside the city of Danlí. This farm is both a family enterprise and a serious experiment. The farm produces a wide variety of fruits and vegetables, eggs, milk, cheese. There are fish ponds. Irrigation is largely gravity fed. Everything is recycled. Some years ago, my Honduran friend took a month-long course at the Southern Institute for Sustainable Technology (SIFAT) in Alabama. This farm puts into practice much of what he learned there, with some additional support from a private community development organization in Europe.

There are other such grassroots experiments in the country. His passionate belief is that Hondurans have the knowledge, skill, and energy to make the country self-reliant in food production. His entire work is to help release that potential. He and his team have been working with hundreds of small farmers and local communities across Honduras. This is the living essence of the dry term “import substitution,” making Honduras self-reliant in food production, and encouraging the innate abilities of its people. It also represents a challenge to the current economy that has depended on exporting the country’s resources in order to have money to pay for imported food and goods—an economy that has only made Honduras and most of its people poorer and more dependent.

Outskirts of Tegucigalpa, Thursday, December 9

Accompanying the driver of a human rights organization as he goes to obtain a part for a car: I observe. We bypass all the regular auto part stores in the city, instead driving out along circuitous roads in the hills above the sprawling capital. Down a narrow dirt road we stop in a small community on the edge of the ever-expanding city. People are busy building their cinder-block houses, gardening. Our driver calls out from the car to a young man working with an older man on a truck in a nearby yard. The youth brings the needed part to the driver. There is no sign, no office, no garage, but this is a car repair, salvage, and mechanic business. On the road back, we pass people laying large plastic bags out to dry in the sun. They run a business rescuing the bags from trash, cleaning them and making them usable again. Further down the road is a man and his teenage son stripping an old mattress to its frame so they can use the frame to make a new mattress out of clean materials. No sign, no office, just this man and his son and a pile of frames working in their front yard by the road. It is a mattress store.

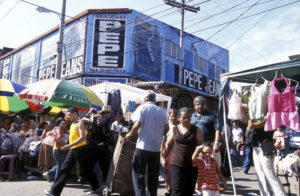

Anywhere in the cities, we see people engaged in home-based micro-businesses—older women selling hot, fresh tortillas by the dozens on the same street corners every day; tiny barber shops; places by the road to get your tire patched; people selling snacks in the streets to passing motorists and bus passengers; people turning discarded materials into usable items for sale. Welcome to what economists have called the “informal” economy.

Foreigners sometimes see this as a sign of the desperation of poor people. But the election of November 28 sheds a different light, providing a different context for understanding this. If nothing else, this election was a loud and clear demand by the Honduran people for change that will allow the people to build their country, rather than selling their labor and the country’s resources to others and getting almost nothing in return. This is more than an economic or even a political matter.

Fundamentally, it concerns rescuing, acknowledging, and supporting the self-identity, dignity, creativity, and spirit of the Honduran people that has for many years been used as a commodity bought and sold by others. Here is a quintessential human rights issue.

If this interpretation is essentially correct, the Honduran people’s clear choice from this election poses a great opportunity for the United States to make good on its often touted commitment to popular democracy, human rights, and self-determination. A healthy and vibrant Honduran people will be the best friends the United States could want.

Some folks may not be happy with this if they are getting rich by extracting the resources of Honduras. But that extractive model, as it is now, is unsustainable, and everyone knows it, especially the Honduran people.

Dr. James Phillips is a retired professor of Anthropology at Southern Oregon University, author, and Chair of the Peace House Board of Directors.