Resilience as resistance, carving out alternatives to the culture of violence and disregard.

Resilience as resistance, carving out alternatives to the culture of violence and disregard.

by Elizabeth V. Hallett

“We knew, in Minneapolis, that terrible things were going on,” said midwife Rebeca Josefina. The death of George Floyd forcefully exposed it…this is not my Minnesota!” These are the words from my friend of forty years, a midwife who is a Cuban refugee. We shared a home together in this George Floyd neighborhood years ago and have been friends ever since. We used to attend births together.

The night after George Floyd was murdered, when the mile-and-a-half section of Chicago Street erupted with demonstrators, looters and fires, we stayed on the phone for hours. The old construct of Minneapolis was unraveling. She had no TV. I would describe what I was seeing in real time CNN coverage. So, we were watching the construct of the past unravel or unfold into a new future. We were watching resistance. What can we re-imagine? What will it be? We seek resilience in a most creative, nonviolent and healing expression for our country.

I called Rebeca again this month. With the entire world, we were watching the conclusion to the Trial of Derek Chauvin over the murder of George Floyd play out. We have, as a people, been unavoidably re-traumatized by video footage: not just that of the murder itself, but by the footage that shows several by-standers all shouting to the four police officers involved, begging them to let up, to take his pulse, to stop hurting George Floyd. We heard from several of the by-standers under questioning in the courtroom. Each one of them feeling tragically responsible for not doing more — for not intervening in some more direct or physical way to make it possible for George Floyd to breathe.

These are people who had automatic humanitarian instincts to intervene that they cannot physically act upon. As they recalled their witness of the fatal moments, they wept through their survival guilt. They all wish they had done more to stop the murder. Video footage records the witnesses, on the verge of physically pulling the officers off George Floyd — begging, pleading. “Get back on the curb!” the policeman is saying. And they did, agonizing, because they were afraid for themselves as well as George Floyd. They had been conditioned to fear the police by all too many instances of police violence. One is threatened with mace. And there they are, hanging in the balance, frozen in time by horror and abusive power at Chicago Street and 38th Avenue in Minneapolis, blocks from where I once lived.

In that moment, the witnesses are all caught, like a tableau, like flies in the amber resin of a time-matrix they do not want to be in. Their wings are stiff and cannot move, as if in the encrusted amber sap of a tree. That matrix is one of a social structure that ultimately immobilizes, kills or maims what does not serve it. It is a structure that ignores the human being – the life of an individual. We all pray to be released, if we become frozen – from such painful dis-empowerment.

And yet, here comes the resistance in the form of then-seventeen-year old Darnella Frazier, with her phone firmly trained on what Derek Chauvin was doing. The memory of the flagrant act of the white policeman, Derek Chauvin, with his knee on the neck of a black man, George Floyd – we say it again – for 9 minutes and 29 seconds – has now being re-lived, re-collected and engraved upon our collective psyche through the witnesses in the trial of Officer Derek Chauvin over and over in the courtroom and on television, sending news around the world. In that horrible moment, Darnella Frazier was not frozen. She deliberately trained her Iphone on an “entitled” white man pressing into a black man’s neck with his knee, while looking calm, intentional and entitled: like he is just doing his job. And we still have three more officers to try in court for holding George Floyd down as his assistants.

Agonizingly, Darnella Frazier testified in court through her tears:

“I heard George Floyd saying “Get off of me. He cried for his mom. He cried for his mom. He was in pain. It seemed like he knew it was up for him… It’s been nights I stayed up apologizing – apologizing to George Floyd for not doing more – and not physically interacting and not saving his life, but it’s not what I should have done. Its what he (Derek Chauvin) should have done.“

Here comes the salvaging grace of a young woman who did what she could do in that sickening moment: recording and eventually speaking truth to power in what is left of our democracy’s judicial system. Here comes a democratic process set up to try for justice. And it actually functioned the way it is meant to function.

The perpetrators seemed to assume that even being video-recorded, even in broad daylight on a Minneapolis, Minnesota thoroughfare, they could do this thing. It is not that all white folks or all cops are like this. But for the ones that are, this time there was no getting away from the scrutiny. And thus the “conversation” about all the other incidents of racist experiences we have endured as a culture and as individuals came tumbling out onto the streets in cities all over the United States. With the human response, the rage, the nonviolent and the violent demonstrations, the old construct of racial violence to the soul our society has come into full view.

It does not seem to matter that George Floyd was possibly passing a counterfeit $20. bill; that he was probably on drugs by his own words; that he had a prison record. What mattered was that he had been discounted as a human being beyond what could be considered necessary, even by Derek Chauvin’s fellow police force witnesses. What matters now is that hundreds of thousands of citizens around our country and around the world who believe in equal justice and nonviolence stood up with Darnella and her fellow witnesses, made signs, marched, and began to demand a change in the structural arrangements of policing in cities around the country. And it continues.

Author and CNN commentator Van Jones, wept with relief on camera saying,“a black man died and everybody cared!”

Other forms of resistance and of resilience take shape through the blues and jazz; through painting and story-telling; through theater, dance and traditional foods that recall comfort and celebrations of life. Within days of George Floyd’s murder, the citizens in the heart of Minneapolis had taken over the street where George Floyd’s murder took place, and painted an enormous mural on the nearby wall, enshrining an and broadcasting the enormity and the force of his life and death. T he loud-talking mural made him bigger than life. Cascades of flowers appeared. From then until now, the area has been cordoned off by the community as a sacred place. Cars cannot pass. Hundreds of people come to pay their respects, to participate in grieving, in prayers for change that might avoid future sorrows. There are memorials to George Floyd all over the country.

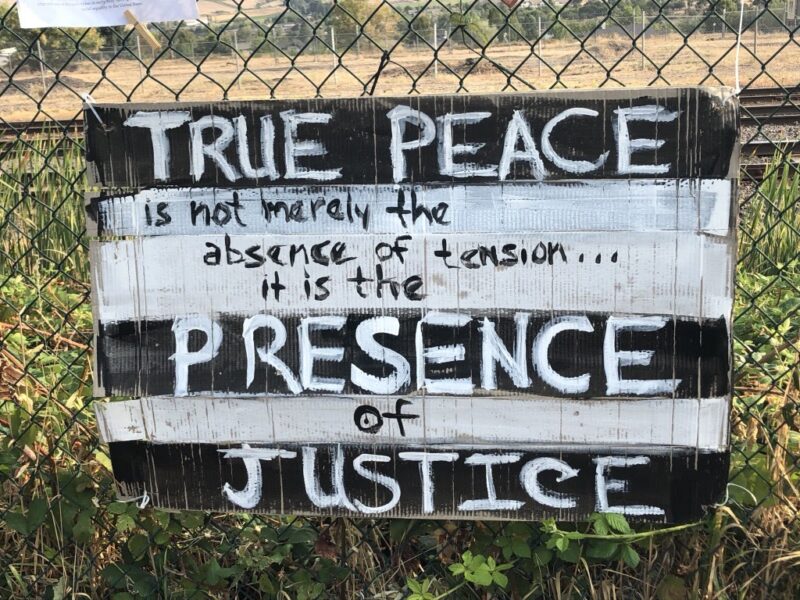

In Ashland we have installed our own forms of art to honor George Floyd and so many – one would be too many – killed by police violence and over-reach. You can see the art installations on the fence along the A Street Railroad past the park. They are part of the “Say Their Names Project.” We call for a culture of nonviolence and a culture of respect and equal justice: a re-imagining of how we handle human beings.

###