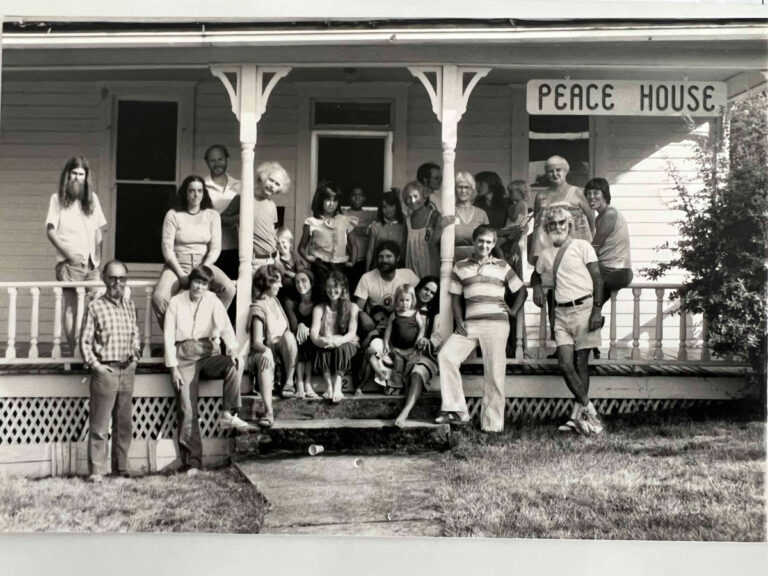

by Elizabeth V. Hallett, Peace House Executive Director

Peace House was established in 1982 by a group of citizens who had successfully campaigned to persuade the City of Ashland to declare itself a Nuclear Free Zone – one of the first in the nation. In the early years the work focused on ending the nuclear arms race between the U.S. and the Soviet Union. Subsequently, Peace House has addressed a wide range of challenges for peace and justice, inequality and hate crimes in our area as well as nationally. Although changing circumstances dictate our program, emphasizing commitment to nonviolent resolution of conflict is the bedrock of all our work.

Our initial sponsor was the National Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR) and eventually Peace House became a nonprofit in its own right and now helps some fledgling groups evolve into full nonprofits of their own.

Our first location was in a house, since torn down, behind the Ashland First Methodist Church.The original founders included several from the Quaker or Friends Meeting persuasion, including John Stahmer, Marjorie Kellogg, Ken Deveny and Bill Ashworth. The Society of Friends belief in nonviolence and war prevention are central aspects of their spiritual practice. These roots and the founders themselves would eventually lead Peace House to actually become co-owners with the Southern Oregon Friends Meeting, after a hiatus operating out of the Ashland Old Armory for several years. The location across from Southern Oregon University, at the intersection of South Mountain Avenue and Ashland Street has often provided collaboration with SOU’s International Students Association, and the Anthropology and Native American Studies Departments.

The First Year

The first year of Peace House, members organized to sustain actions aimed at halting nuclear war. There were monthly silent candlelight vigils held and that year four Ashland women got arrested at an action at the Mother’ Day Livermore Lab Blockade. Later, Ashlanders also blockaded Vandenberg Air Force Base. The first Hiroshima-Nagasaki Vigil was held. That was just the beginning!

Through your loyal support and foundation grants, Peace House has been able to provide a platform for the exploration of nonviolence and address issues in drastic need of positive social change. It is a place of collaboration, synthesis, and a fervent belief in nonviolence as a practice.

The 1980’s focused on direct action demonstrations calling out weapons manufacturers, and the Gulf War, the Central American Wars, and support for refugees fleeing El Salvador and Guatemala. In 1983, for instance, there were weekly vigils held at Litton Industries, an arms manufacturer, in Grants Pass; a nonviolent “Refuse the Cruise” anti-missile action in Portland.

An Ashland delegation joined the National Freeze Campaign Citizens’ Lobby in Washington to deliver letters to Congress. In 1984 Peace House participated in a statewide campaign to declare Oregon a nuclear free zone. During a Freeze campaign National Strike Day event in Ashland, 40 businesses closed. Later a three-day Ashland festival for peace, unity, and action was held.

At the same time awareness of the plight of Central Americans caught in war was building. Emissaries from Peace House traveled to Nicaragua with Witness for Peace and returned with community programs.

Central American Solidarity

In 1985, work began with the Interfaith Sanctuary Network for Central American Refugees and Peace House supported a Nicaragua Ambulance Fund Drive. Peace House joined the National Pledge of Resistance, a nonviolent actions designed to turn out demonstrators as an immediate response mechanism to call attention to US sponsored military escalations in El Salvador and Nicaragua. That year, Peace House members also participated in an Easter Week Vigil at the Nevada Test Site.

Concerns were for civilians affected by war in Guatemala, El Salvador, Nicaragua and Honduras. In the 1980’s. Peace House assisted Central American refugees and there was a caravan to help in Nicaragua after the hurricane in 1988 as well as co-sponsorship of a Refugee Care Project with the MulltiCultural Association.

And so it went. By 1987 Women’s issues and rights also began to get more visibility in the peace movement, and a “Women of the World for Peace” event was held to support Women’s History Month that year. Local nonviolence training workshops appeared as part of Peace House programming. Also, delegates from Ashland participated in a conference that resulted in the creation of PeaceWorks, a statewide organizing platform for a culture of nonviolence and social action. Through the 1980’s, the voices of nationally known pro-peace thought leaders who Peace House sponsored included Daniel Berrigan, Jim and Shelly Douglass (White Train organizers).

In 1988 Peace House shifted from mainly nuclear issues to encompass a wider range of peace and justice issues.

By 1989, Peace House was shifting to expand into other areas of social justice besides concerns about war. At a “Unite for Peace” conference, Dr. Benjamin Spock addressed the concerns of war as related to children and families. Maggie Kuhn of the Gray Panthers spoke of the need for elder support. In an ironic twist, this was also the year that Peace House acquired a new office in the Old Ashland Armory.

The 1990’s were generally a time of working on war avoidance, nuclear war and nuclear waste issues, racism, homophobia, homelessness, hunger, nonviolent communication, and Central American, Native American and Farmworker solidarity networks. There were also forums on International issues surrounding US policy in the Middle East in Central America.

In 1990 Peace House offered tax resistance information and promoted the World Peace Tax Fund Bill and also organized support for the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty. Concerns over Central America continued discussions about the 1990 Nicaraguan elections that year.

In 1992 the Gulf War subsided and local needs took a bigger amount of Peace House attention. Uncle Food’s Diner, a Tuesday Community Meal Project began to address hunger and homelessness. It grew and moved from the Senior Center to Trinity Church a year later. The Diner was to become a central feature and rallying point for community in Ashland. Uncle Food’s Diner (named by some young students) began as a small project to provide community and a meal for houseless teen agers. This quickly grew into a weekly meal for anyone in need of community or food. (See an update at the end of this summary.)

In 1993 and 1994, there was collaboration with the MultiCultural Center to bring “Teaching Tolerance” into the schools and churches as part of education outreach. Rev. Dr. Richard Deats, from our then-parent organization, Fellowship of Reconciliation, visited and spoke on “Dealing With Hate.” Peace House worked with the MultiCultural Center to bring “Teaching Tolerance” into local schools and churches as part of education outreach. There were programs with with known activists Evangelinna Rodriguez-Lopez, Peg Morton and Helena Norberg-Hodge.

Generally Peace House expanded to offer workshops in nonviolent communication skills initiating innovative communication styles to address forms of anger, prejudice and hate.

Attention also expanded to address the “uberculture” of militarism and repression as evidenced in the lack of practical survival resources for housing, food and education that many are experiencing in our society.

From 1993 to 1995 there were successful listening projects on abortion and “Gay and Lesbian” rights – long before LGBTQI became an acronym. Later, Peace House also sponsored a listening project on forestry issues (1997) that led to the formation of the Ashland Watershed Alliance, after controversies swirled about clear cutting vs. forest management. This was, perhaps, the beginning of a formal fusion between Peace House themes of nonviolence and an understanding of protection of our Earth, our trees and our water as a form of nonviolence. Clearly, Native people have known and lived by this principle all along, but many times we get segmented into movements and lose sight of the whole picture.

In 1997 the Community Action Network (which Peace House helped to start) began of a Listening Project on Forestry issues. This morphed into the Ashland Watershed Alliance in in 2002, creating a collaborative relationship between eco-activists and the Jackson County Forest Service after a precarious period of conflict resolution. This year documentary film producer Byron Hurt spoke on Afro-American male issues in America.

In 2002, along with the obvious topics in our evolution, another social concerns theme emerged as Peace House-led community conversations to discuss firearm safety. David Barsamian,co-founder of Democracy Now, spoke

Avoiding War

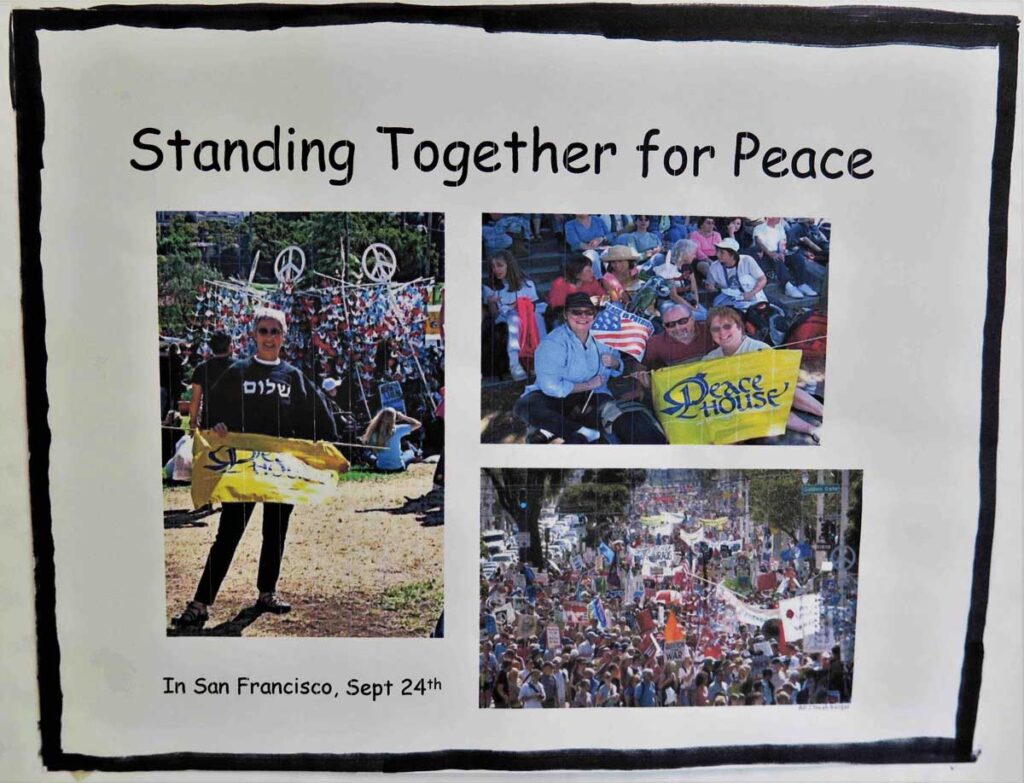

Preventing or ending war, and especially nuclear war, have been part of Peace House concerns for four decades, publicizing the issues of U.S. aggression have prevailed through the Central American wars, the Gulf War, the Iraq War, the Afghanistan War. There has been anti-militarism education and also support for veterans who are troubled by what they have been through and seen. Veterans For Peace Has been a long-time ally. The Hiroshima-Nagasaki Vigil begun in 1982 prevails each year to date on August 6th, the day the first Atomic Bomb was dropped on Japanese people.

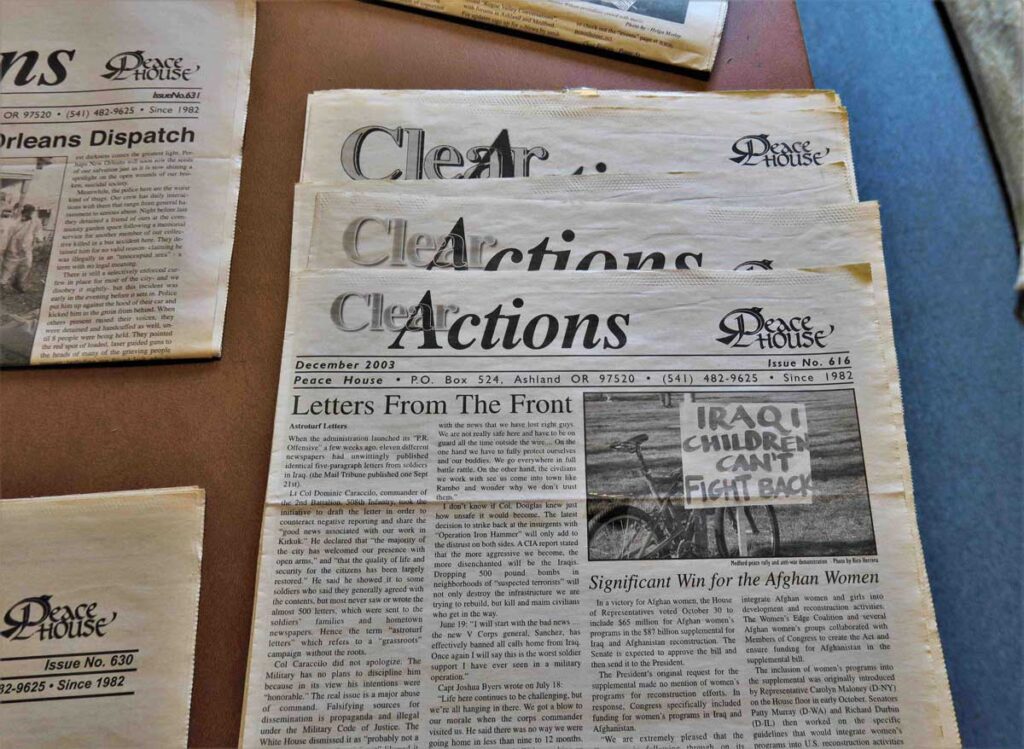

Clear Actions Newsletter Forty Years Later

The first Clear Actions newsletter – then called “Nuclear Reactions” – was published in 1983 and there was serious tax resistance leafleting. Initially, the publication highlighted the issues of nuclear waste in Oregon and of the nuclear threat through resistance at the Nevada Test Site, with several Ashlanders making the trip to participate.

Clear Actions has been a mainstay and a hub in the Rogue Valley for communication of peace social justice issues since 1983, moving from print to digital several years ago and featuring articles that support a culture of nonviolence locally, statewide and beyond. It has been a way to disseminate information challenging hate and violence; advocating diversity and equality; and promoting social and climate justice across a spectrum. Clear Actions continues to feature allied social action groups in our Community Calendar and offers a nonviolent vision toward racial, gender, and economic equality for the future.

In 1993 Uncle Food’s Diner (named by some young students) began as a small project to provide community and a meal for houseless teenagers. This quickly grew into a weekly meal for anyone in need of community or food. While the dinner guests have changed from week to week, the number served has been at about eighty each week.

Amazingly, this program scaled up to four times per week during the COVID pandemic, when meals could not be served inside and resources were limited. Our teams cooked and delivered food to five locations on the streets of Ashland for almost two years, helped by special COVID grant funding. We were also able to provide food for shelter residents with OHRA and Rogue Retreat, as well as those displaced by fires. Community collaboration with Jobs With Justice and The Monday Meal made meals possible seven days a week and this pattern has continued.