Read entire article “Sequestration and Its Impact on Non-Defense Appropriations“

Effects on Overall Non-Defense Appropriations

Due to the BCA caps, sequestration, and the subsequent modifications to sequestration, non-defense appropriations have been almost flat since 2012 in actual dollar terms, apart from a sharp dip in 2013. The 2014 total is only about 1 percent larger than it was two years earlier, and the 2015 total is just 0.1 percent above the 2014 level.[6] That’s because, with the exception of 2013, the modified sequestration cuts have roughly been offset by scheduled increases in the underlying caps.

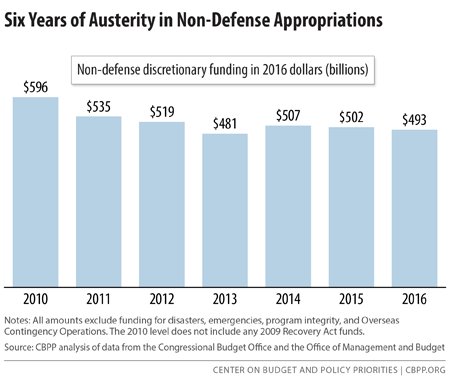

Funding totals that are stable or falling in actual dollar terms mean substantial real cuts when we consider the effects of inflation, as shown in Figure 2. Measured in constant 2016 dollars, the 2015 cap on non-defense appropriations is $94 billion, or 16 percent, below the comparable 2010 level.[7]

If policymakers do not further adjust sequestration, the 2016 cap will be $493.5 billion, which is only slightly above the 2015 cap — growing by just $1.1 billion (0.2 percent). That’s because the original (pre-sequestration) cap rises by $10 billion in 2016 but the sequestered amount rises by $8.9 billion, almost entirely due to the loss of the sequestration relief that the Murray-Ryan deal provided for 2015.[8] (See Table 1.)

As a result, 2016 will be yet another year in which any dollar increases for urgent needs or high-priority programs must be offset by cuts elsewhere. For example, with a virtually flat cap on non-defense appropriations, policymakers will need to offset rising costs of health care and other services for veterans (for which Congress has already enacted an increase through advance appropriations); and they would also need to offset the cost of doing things like reversing previous cuts in medical research, expanding early childhood education, or tightening border security. Even where programs do not fall in dollar terms, inflation will continue to erode the purchasing power of appropriations. Overall, the 2016 cap would be 17 percent below the comparable 2010 level after adjustment for inflation.

In 2017, the caps will start rising even with sequestration fully in place, because the underlying BCA caps rise while non-defense sequestration remains fairly constant in dollar terms. The increase will only roughly match the rate of inflation, however, with no adjustment for population growth or other needs. Thus, inflation-adjusted non-defense appropriations would finally stop falling, but will stabilize at levels greatly reduced from 2010.

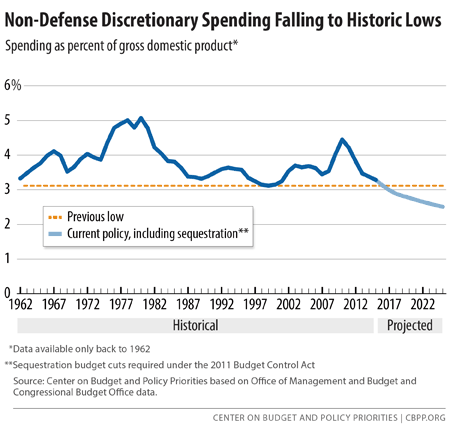

The decline is even sharper when we measure spending relative to gross domestic product (GDP) — a standard way of comparing spending over long periods. On this basis, outlays for non-defense discretionary programs have been shrinking steadily since 2010. Current Congressional Budget Office projections indicate that, under the caps and sequestration currently in place, outlays for these programs in 2016 will be 3.1 percent of GDP, equal to the lowest percentage on record (with data back to 1962). That percentage will continue to fall if the caps and sequestration remain unchanged, setting a new record low in 2017 and falling further after that. (See Figure 3.)

In short, the BCA, with its caps and sequestration, will soon mean that the federal government is devoting the lowest share of national income in at least five decades to the services and investments covered by non-defense appropriations.

Annual Caps on Non-Defense Appropriations (in billions) | ||||

| 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | Change, 2015 to 2016 | |

| BCA Caps Before Sequestration | $506.0 | $520.0 | $530.0 | +$10.0 |

| Sequestration Cuts | -36.6 | -36.9 | -36.5 | +0.4 |

| Murray-Ryan Agreement | +22.4 | +9.2 | 0.0 | -9.2 |

| Resulting Caps | 491.8 | 492.4 | 493.5 | +1.1 |

| Note: Figures may not add to totals due to rounding. The BCA is the 2011 Budget Control Act, The Murray-Ryan budget agreement is the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2013. Source: Office of Management and Budget | ||||

The BCA’s Two Different Types of Sequestration

The BCA actually establishes two different types of sequestration that could potentially apply to appropriations. One, which is the focus of this paper, produces additional budget cuts as a replacement for the deficit reduction that the supercommittee was supposed to achieve. The other enforces the appropriations caps. Because both types are often simply referred to as “sequestration,” confusion sometimes results.

In general, sequestration is a process established by law through which the executive branch reduces certain funding based on specified triggers and formulas. Policymakers have used it from time to time to enforce various budget limits, including deficit targets set by the 1985 Gramm-Rudman-Hollings Act and appropriations caps and pay-as-you-go rules under the 1990 Budget Enforcement Act.

The first type of sequestration that the BCA established simply enforces the appropriations caps set by that law. Under this process, after Congress adjourns at the end of a session, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) is required to evaluate the enacted appropriations to determine whether they comply with the caps. If it finds a violation, OMB must apply uniform percentage cuts to appropriations in the category where the overage occurred in order to eliminate it. With one very tiny exception, this type of sequestration has never been triggered. It won’t likely be triggered in the future either, since Congress won’t likely enact appropriations that exceed a cap knowing the result will be across-the-board cuts.

As discussed in this paper, the BCA also established a second type of sequestration, to produce additional spending cuts in the event that the supercommittee process failed. This sequestration process was triggered beginning in 2013 and remains in place. It operated through across-the-board cuts in 2013, making it superficially resemble the first type of sequestration — except that its purpose was to produce further spending cuts even though Congress had complied with the applicable appropriations caps. For 2014 and all subsequent years through 2021, this supercommittee-related sequestration operates by reducing the caps below the levels that the BCA set, as this paper explains. And if policymakers enacted appropriations that exceeded the reduced caps, the first type of sequestration would then also be triggered to eliminate the violation.