By Julian Borger (Originally published on The Guardian)

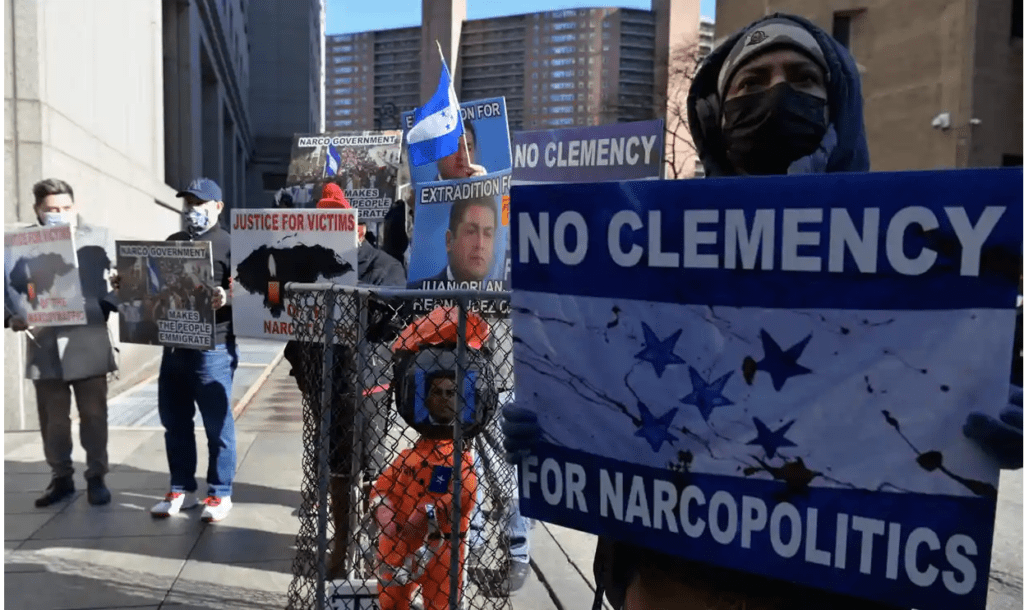

For the US, this is a painfully embarrassing fortnight to count Honduran president Juan Orlando Hernández as a key ally in Central America.

On Monday he was named in a New York federal courtroom as a co-conspirator in the conviction of his associate, Geovanny Fuentes Ramirez, for smuggling tons of cocaine into the US, and receiving a $250,000 bribe from Fuentes, an alleged drug kingpin.

Next week, the president’s brother, Tony Hernández, is expected to be sentenced in the same New York court for his own drug trafficking conviction. At his trial President Hernández was implicated by Devis Leonel Rivera, the leader of a Honduran cartel, “Los Cachiros”, who alleged the Honduran leader received millions of dollars in bribes from drug traffickers to protect cocaine shipments to the US.

Rivera, who confessed to ordering 78 murders, cooperated with the DEA since 2013 before turning himself in the following year. He proved to be a devastating witness, providing a detailed account of his relationship with the Hernández family.

Prosecutors in the Fuentes trial said President Hernández had vowed to use his country’s security forces to “flood the United States with cocaine.”

The president has rejected the allegations, describing the testimony implicating him as “false” and “obvious lies”, and has claimed success in restricting the flow of drugs through his country to the US.

Despite the growing pile of incriminating testimony, Washington has been silent on the links between the Honduran government and drug money, in contrast the routinely vociferous condemnation of corruption in Venezuela, Cuba and other left wing Latin American states.

“I think one of the frameworks that you can look at foreign policy towards Latin America with, is this lingering effect of the cold war,” said Christine Wade, the director of the international studies program at Washington College in Maryland.

“In many foreign policy circles we have a tendency to look at the world, and in Latin America in particular, in terms of left and right, with the left as bad guys and the right as the good guys.”

US policy towards Hernández has generally treated him as a staunch regional ally in dealing with migration and drug trafficking, at odds with the justice department’s legal pursuit of his family.

Hernández has sought to draw on past familiarity with Joe Biden for his political survival, posting a photo of the two men together on his Twitter account after the November US election.

“We will have to sit down, talk and see the progress that has been made” in Honduras, he told the Washington Post.

He added: “I always felt that Biden was more pragmatic” than Trump, “and always very courteous.”

But there are signs the tide is beginning to turn in Washington on the flamboyant Honduran leader. The Biden administration is expected to take a cooler approach to President Hernández than Donald Trump, who legitimised his reelection in 2017 despite widespread concerns about rigging.

Trump hosted Hernández in Florida and claimed “We are stopping drugs like never before ”.

The new administration has suspended Trump-era agreements with Honduras, Guatemala and El Salvador under which asylum-seekers had to apply from the central American countries for US asylum, in return for favourable treatment of their governments.

Eight US senators introduced a bill in February to suspend security aid to Honduras because of what they called substantial evidence that President Hernández “has engaged in a pattern of criminal activity and used the state apparatus to protect and facilitate drug trafficking ”.

“I think that in the last few months we’ve seen increasing congressional pressure on Central America, and I think that it is going to be really hard to keep looking the other way on Honduras,” Wade said.

“The approach I suspect we’ll see from Biden will be more prescriptive and that’s inevitably going to mean addressing some of these corruption and organized crime issues.”

But she added: “I think the general tenor of US policy won’t change. The preference of US policy in dealing with crime in the region is militarization … I don’t necessarily expect that to change. We have a broken immigration system. That is most certainly not going to change overnight.”