by James Phillips Originally published on Counterpunch.org

August 30 each year is commemorated as the Day of the Disappeared in many parts of the world. In Honduras, labor unions, students and teachers organizations, human rights and women’s groups and others typically mark the day with a massive public march through some of the main streets of Tegucigalpa, the Honduran capital. The march can stretch for a mile or more and last for three hours. But why such an outpouring for those who have disappeared?

Every day, people disappear in many parts of the world. Some of these disappearances are investigated by police and the family of the disappeared. But too often the perpetrator is not a criminal or a gang, but rather the police or other agents of a nation state or a government. We have many examples of these sorts of disappearances in the past. The military dictatorships of Argentina, Brazil, and Chile in the 1970s disappeared thousands of people. We have seen how mothers of those whom the Argentine state disappeared continued for years to demonstrate and vigil in the Plaza de Mayo in central Buenos Aires with a demand for accountability from the authorities: “Donde están?” Where are they? In Chile during the Pinochet dictatorship, mothers would make the rounds of hospitals, prisons, and morgues looking for their disappeared loved ones. Many of them met in these places and began to form a network that quickly became a movement similar to that in Argentina. These older mothers and grandmothers became so powerful with their witness, that a police officer said to one of the mothers, “We made a mistake in not disappearing you, too.”

Today, relatives of Central American migrants who disappear while crossing Mexico to reach the U.S. border continue to demand investigation and accounting from Mexican authorities. Receiving little support from the authorities, relatives and friends try to arrange their own investigations with the help of international organizations. Today, in the United States and Canada, Native American tribes and First Nations suffer the disappearances of many young Native women, and they have begun the Red Dress movement—an ongoing denunciation of the disappearances and a way to honor the disappeared. Recently, the mass graves of Native children have been found near the “Indian boarding schools” the Canadian government forced them to attend. In most cases, even after decades, the schools and the authorities never told the parents what had happened to their children.

In the early 1980s in Honduras, the military-dominated government, applying the national security doctrine—the idea that the security of the state was more important than the rights of people—began detaining many leaders and members of teachers and student groups, labor unions, and political parties. The national security doctrine first developed in the U.S. in the late 1940s and 1950s in the early Cold War, anti-Communist, and McCarthy black list context. The doctrine was adapted by dictatorships and militaries in Latin America in the 1970s and 1980s, including the Honduran military. Meanwhile, the United States was directing both the economic development policy and the military policy of Honduras, making the country the base for U.S. intervention against Nicaragua (i.e., the Contra war). The U.S. military worked closely with the Honduran military to eradicate the threat of “communism.”

In many cases, people detained in police or military custody in Honduras were never seen or heard from again. The number of such detained and disappeared people was said to be as many as two hundred, but that is widely believed to be a serious undercount because of the fear of families to report these events or the inability of poor families to know how to access help. The Honduran military operated what many called a “death squad” (Battalion 316). Detention in military or police custody was very likely to lead to disappearance, torture, and death. But relatives of the disappeared never knew for sure the fate of their loved ones.

In this dire context, in 1982 a group of relatives of some of the disappeared formed the Committee of Families of the Detained/Disappeared in Honduras (COFADEH, its Spanish acronym). One of the founders was Bertha Oliva, whose husband, Tomas Nativi, had been detained and disappeared by Honduran security forces along with others in 1981. Oliva has continued as director of COFADEH for the past 39 years. For most of these years, she and the COFADEH staff have suffered police surveillance, harassment, stalking, death threats against them and family members, and public attempts by authorities and media to defame them and their work. That work has expanded, especially in the years since the 2009 coup, to include providing legal support and representation not only for families of the disappeared but also for people who have been criminalized or imprisoned by state authorities for peaceful protest. The wider logic is that detention can lead to disappearance, torture, and death, so early intervention on behalf of the detained may be crucial.

Disappearances have again emerged as a deadly reality of political repression in Honduras under the governments that have ruled since they seized power in a coup in 2009. One of the more well-know examples is the kidnapping and disappearance of five young men from the Garifuna Indigenous community of Triunfo de la Cruz in the north of the country, by heavily armed men more than a year ago.The Garifuna have been under extreme pressure from the government and private entrepreneurs who want control of Garifuna land and resources for agribusiness and tourism. The disappeared men were/are active leaders in peaceful attempts to defend the land and resources. Their fate remains unknown, and the Honduran state has made no serious attempt to find the men or bring the perpetrators of the kidnapping to justice. Many Hondurans are convinced that the government is, at the least, complicit in the disappearances, in support of powerful interests wanting to take Garifuna land, or with drug lords. The disappeared Garifuna men are: Alberth Santana Centeno, Milton Martinez, Suamy Aoaricio Mejía, Alberth Santana Thomas, and Gerardo Mizael Róchez. The rallying cry of the Garifuna community has become: “They were taken from us alive; we want them back alive” (Vivos se los llevaron; vivos los queremos).

Why would governments—or more precisely the powerful people who control governments—not simply assassinate opposition leaders? This does happen, and it conveys a stark and unambiguous message to others contemplating protest or peaceful resistance. But disappearance has its own insidious logic that is in some ways even more effective than assassinations. Disappearing someone leaves no evidence, no remains, no weapons, nothing for foreign forensic scientists to examine. The government is protected by “plausible deniability.” Authorities can claim that they had nothing to do with whatever their agents and underlings might have done. The uncertainty allows for fake narratives and “alternative facts.” An actual example reported in a Honduran newspaper: when interviewed, authorities speculated that the labor union leader who disappeared must have absconded with the union funds or run away with his mistress. In other words, this was a common criminal incident, not an act of political repression—creating an alternative explanation. Unfortunately for those who control the state, ordinary people are often so well accustomed to political repression in various forms that they meet these denials and alternative explanations with considerable skepticism or disbelief; this is certainly the case in Honduras.

Disappearance as a weapon of political repression has another useful characteristic: it creates fear and uncertainty, an unsettled state. Disappearance is a vehicle for creating a confused and unsettled population that can be more easily controlled. The personal pain and trauma that the disappearance of a loved one causes is ongoing, often for many years, across generations and is often experienced as unending psychological torture. It does not have the finality of knowing. There is no physical focal point or end point, no remains, no martyr. To be absolutely clear, disappearing someone is a gross violation of human rights, the rights of the disappeared to the safety and integrity of their own bodies, and of the mental and emotional security of their families and loved ones. It is also, to some significant extent, a violation of the rights of an entire society that loses one of its members in a way that cannot be reconciled or accounted for. In Honduras, everyone knows that disappearance is the likely prequel to torture, mutilation, and killing. It happens all too often. But the salt in the wound is that you never know for sure.

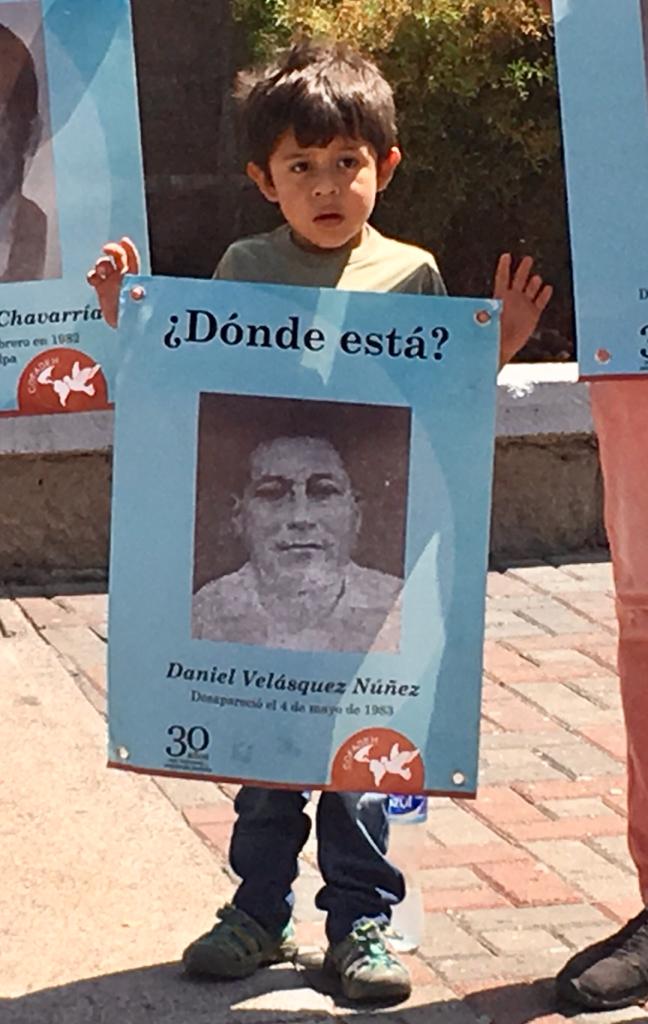

Hondurans who have long experience with the horror of state sponsored political disappearances do appeal to a range of Honduran and international laws, covenants, and treaties against disappearance, but these must have the compliance of the government to be effective—asking the perpetrators to investigate themselves, which is highly unlikely. People and organizations have at least two other more potent responses: memory work and international solidarity. Popular organizations often begin their large meetings with a ceremony to remember by name those among them who have been assassinated or disappeared. Disappearing people is a form of trying to erase their very existence, as if they never lived. Remembering always those who have disappeared is a way to reaffirm their human existence and identity and honor them for who they were/are. People shout “Presente!” as the names of the disappeared and assassinated are mentioned. On both a personal and a social level, remembering is thus also a powerful form of resistance to political repression.

As a Honduran organization, COFADEH is a good example of the struggle against political disappearances. COFADEH’s primary mission has been precisely this keeping of memory alive “contra el olvido” (against the forgetting). Forgetting is not just an innocent slip. In this context it is regarded as a deadly weapon of repression and dehumanization that must be countered. The photos of many of those disappeared in the early 1980s, and some since, appear on walls in the COFADEH office in Tegucigalpa. The organization has been developing a “Ruta de la Memoria Histórica,” a route along which stops would mark the sites of places where the detained and disappeared in the 1980s were known to have been held, torture, or killed. Along the route would be the Casa del Terror, the Museum of Living Memories, the Plaza of the Disappeared, the hill where the remains of disappeared individuals were found, and at the end of the route, the Hogar contra el Olvido, a representation of the hearth or home, the center of family life that has been so under attack from political disappearances.

In addition to keeping memory alive, COFADEH engages in two other critical missions. It provides legal support and voice for Hondurans detained by the police or the government for exercising their political rights, or under false accusations. The experience of those who founded COFADEH and of many other Hondurans is that detention by state authorities in Honduras has too often led to disappearance in police custody, and the individual is never seen or heard from again. Intervening early in this deadly process is crucial. COFADEH also relies on international solidarity, the awareness and support of organizations abroad. Solidarity here is most effective before an individual has been disappeared, but it is also important in providing international presence and protection to local people for attempts to investigate and demand official accounting for the disappeared.

The massive Day of the Disappeared marches in Honduras each year include a wide variety of organizations, each with its particular concerns. In effect, countering the evil of disappearance as a weapon of political repression is a crucial part of the larger struggle for social justice, human rights, dignity, and democratic accountability.

Note: Peace House is a cosponsor of local resident Lucy Edwards in her volunteer work of human rights accompaniment for Berta Oliva, coordinator of COFADEH. Lucy is a volunteer with the Honduran Accompaniment Project (Proah).