When Remembering Is a Political Act of Resistance

by Jim Phillips

In many areas of the world, August 30 each year is commemorated as the International Day of Victims of Forced Disappearance. In Honduras, this day is known as the National Day of the Detained and Disappeared, and is typically marked by a massive public march through some of the main streets of Tegucigalpa, the Honduran capital. The march can stretch for a mile or more and last for three hours.

Every day, people disappear in many parts of the world. Some of these disappearances are perpetrated by criminals and gangs and may be investigated by police and the family of the disappeared. But too often the perpetrator is not a criminal or a gang, but rather the police or other agents of a nation state or a government. We have many examples of these sorts of disappearances in the past. Latin American countries have an especially troubled history with state-sponsored disappearances of people whose only crime was voicing their peaceful opposition to their government. The United States government was deeply involved in this history.

Operation Condor

Operation Condor included police and military roundups of thousands of people, detention, and widespread use of torture. Between 1975 and 1982, thousands were killed, and thousands disappeared while in police and military custody in the countries where Operation Condor was in force—Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay—and was also happening in Chile, Guatemala, and Honduras. With the return of civilian government in Argentina, a National Commission Concerning the Disappearance of Persons was formed. This Commissions 1983 report detailed 8961 disappearances in Argentina during the time of Operation Condor and the military dictatorship. The country had 380 secret detention and torture centers. The situation was similar in Chile, Brazil, and Paraguay, all under military dictatorships.

For many years after, no significant investigation or prosecution of the perpetrators was possible because the perpetrators were still powerfully present. In the 1980s, an independent commission investigating the Mayan genocide issued its report implicating the military. Within a few days, the Catholic bishop who chaired the commission was murdered. In September, 2013, the Guatemalan newspaper Plaza Pública published a 55-page report detailing each of 250 or more people disappeared by the military, although the actual number of disappeared was probably much larger. The report, or a copy of it, was later archived in the Nation Security Archives at George Washington University in the United States.

Recent Examples of Forced Disappearance

Unfortunately, the use of forced disappearance as a political weapon is not confined to the past, nor to military dictatorships. In 2014 in Mexico, a bus full of mostly Indigenous students was attacked near Ayotzinapa in Guerrero state; 43 students were disappeared. It was soon revealed that the perpetrators were Mexican police in collusion with drug traffickers. Parents of the disappeared students, supported by an international campaign, kept up the demand that the Mexican state find their children and prosecute the perpetrators.After years, the bodies were found. This year, the Mexican government finally admitted culpability and moved to prosecute the former Attorney General and others. The only solace for the families was, at last, the knowledge of what had happened to their children, a psychological closure of sorts, the possibility of accountability, and perhaps the awareness of some international solidarity supporting them.

Currently in the United States and Canada, hundreds of Native American and First Nations women have been disappearing from reservations and towns. By 2016, at least 5712 American Indian and Alaskan Native women were reported missing, but the actual number is probably higher. Meanwhile, the horrors of the Indigenous boarding schools in Canada and the U.S. are now coming increasingly to light. The schools forcibly took Native children from families and tribes and kept them in boarding schools where the purpose was to eradicate Indigenous culture and identity. The recent discovery of mass graves at some boarding schools (e.g., near Kamloops in British Columbia) revealed that hundreds of Native children had died under the harsh conditions of the schools. Their bodies were buried quietly on school grounds, and their families and tribal communities were never told what had happened to them—they were simply “disappeared.” For some older Native people today, words fail to describe the grief of having their children or grandchildren, or brothers and sisters taken from them and their culture and identity erased, and then not knowing what happened to them.

Disappearances and Detention in Honduras

In the early 1980s in Honduras, the nominally civilian but military-dominated government, began detaining many leaders and members of teachers and student groups, labor unions, and political parties, and even priests and male teenagers. Meanwhile, the United States was directing both the economic development policy and the military policy of Honduras, making the country the base for U.S. intervention against Nicaragua in the Contra war. The U.S. military worked closely with the Honduran military to eradicate the threat of “communism” and to ensure that Honduras did not become like neighboring revolutionary Nicaragua.

In the early 1980s in Honduras, the nominally civilian but military-dominated government, began detaining many leaders and members of teachers and student groups, labor unions, and political parties, and even priests and male teenagers. Meanwhile, the United States was directing both the economic development policy and the military policy of Honduras, making the country the base for U.S. intervention against Nicaragua in the Contra war. The U.S. military worked closely with the Honduran military to eradicate the threat of “communism” and to ensure that Honduras did not become like neighboring revolutionary Nicaragua.

In many cases, people detained in police or military custody in Honduras were never seen or heard from again. The number of such detained and disappeared people was said to be as many as two hundred, but that is widely believed to be a serious under count because of the fear of families to report these events or the inability of poor families to know how to access help. The Honduran military operated what many called a “death squad” (Battalion 316). Detention in military or police custody was very likely to lead to disappearance, torture, and death. But relatives of the disappeared never knew for sure the fate of their loved ones.

In this dire context, in 1982 a group of relatives of some of the disappeared formed the Committee of Families of the Detained/Disappeared in Honduras (COFADEH, its Spanish acronym). One of the founders was Bertha Oliva, whose husband, Tomas Nativí, had been detained and disappeared by Honduran security forces along with many others in 1981. Oliva has continued as the general coordinator of COFADEH for the past 39 years. For most of these years, she and the COFADEH staff have suffered police surveillance, harassment, stalking, death threats against them and family members, and public attempts by authorities and media to defame them and their work. That work has expanded, especially in the years since the 2009 coup, to include providing legal support and representation not only for families of the disappeared but also for people who have been criminalized or imprisoned by state authorities for peaceful protest. The wider logic is that detention can lead to disappearance, torture, and death, so early intervention on behalf of the detained may be crucial.

Although there is a new Honduran government in power that is committed to reform, the terror and pain of disappearances continues. It has been more than two years since five young men from the Garifuna Indigenous community of Triunfo de la Cruz were kidnapped by heavily armed men dressed as police. The disappeared men were/are active leaders in peaceful attempts to defend the community’s land and resources. Their fate remains unknown, and the Honduran state has made no serious attempt to find the men or bring the perpetrators of the kidnapping to justice. The country’s Attorney General, a holdover from the previous corrupt government, even threatened to bring criminal charges against Garifuna people who have been demonstrating in front of his office demanding a more vigorous effort to find the disappeared. The rallying cry of the Garifuna community has become: “They were taken from us alive; we want them back alive” (Vivos se los llevaron; vivos los queremos).

Although there is a new Honduran government in power that is committed to reform, the terror and pain of disappearances continues. It has been more than two years since five young men from the Garifuna Indigenous community of Triunfo de la Cruz were kidnapped by heavily armed men dressed as police. The disappeared men were/are active leaders in peaceful attempts to defend the community’s land and resources. Their fate remains unknown, and the Honduran state has made no serious attempt to find the men or bring the perpetrators of the kidnapping to justice. The country’s Attorney General, a holdover from the previous corrupt government, even threatened to bring criminal charges against Garifuna people who have been demonstrating in front of his office demanding a more vigorous effort to find the disappeared. The rallying cry of the Garifuna community has become: “They were taken from us alive; we want them back alive” (Vivos se los llevaron; vivos los queremos).

Why Forced Disappearance?

Why would governments—or more precisely the powerful people who control governments—not simply assassinate opposition leaders to convey a stark and unambiguous message to others contemplating protest or peaceful resistance? Disappearance has its own insidious logic that is in some ways even more effective than assassination. Disappearing someone leaves no evidence, no remains, no weapons, nothing for foreign forensic scientists to examine. The government is protected by “plausible deniability.” Authorities can claim that they had nothing to do with whatever their agents and underlings might have done. The uncertainty allows for fake narratives and “alternative facts.” An actual example reported in a Honduran newspaper: when interviewed, authorities speculated that the labor union leader who disappeared must have absconded with the union funds or run away with his mistress. In other words, this was a common criminal incident, not an act of political repression—creating an alternative explanation. Unfortunately for those who control the state, ordinary people are often so accustomed to political repression in various forms that they meet these denials and alternative explanations with considerable skepticism or disbelief; this is certainly the case in Honduras.

Disappearance as a weapon of political repression has another useful characteristic: it creates fear and uncertainty. Disappearance is a vehicle for creating a confused and unsettled population that can (perhaps) be more easily controlled. The personal pain and trauma that the disappearance of a loved one causes is ongoing, often for many years, across generations and is often experienced as unending psychological torture. It does not have the finality of knowing. There is no physical focal point or end point, no remains, no martyr. To be absolutely clear, disappearing someone is a gross violation of human rights, the rights of the disappeared to the safety and integrity of their own bodies, and of the mental and emotional security of their families and loved ones. It is also, to some significant extent, a violation of the rights of an entire society that loses one of its members in a way that cannot be reconciled or accounted for. In Honduras, everyone knows that disappearance is the likely prequel to torture, mutilation, and killing. It happens all too often. But the salt in the wound is that you never know for sure.

But people and communities always push back against those who use disappearance as a weapon of control. In Argentina during the military dictatorship of the 1980s, the mothers and grandmothers of the disappeared came out each week to vigil and protest in the Plaza de Mayo in the middle of Buenos Aires, and continued after the return of the civilian government. Their tenacity was recognized worldwide and is credited with the beginnings of investigations into the disappearances after the return of civilian government in the 1980s. In Chile, mothers and grandmothers of the disappeared also protested and showed up at police stations and public places with signs demanding “Where are they?” (Donde están?) One police official told some of these persistent grandmothers, “We made a mistake in not disappearing you, too.” Many of the disappeared in Latin America have never been found. In Mexico and Guatemala, the pressure of persistent demands and organizing from the families and friends of the disappeared, supported by international awareness and solidarity, have led to efforts toward resolution, at least the knowledge of what happened to loved ones, and that there may be some accountability coming.

Remembering the Disappeared

In Canada and the U.S., Native communities carry on several campaigns, such as the Red Dress (Redress) campaign demanding the end of disappearances of Native women, accountability, and making the loss visible with the symbol of the red dress—red, the color of lifeblood, as one activist said. Native communities have also pursued the discovery of the mass graves of Native children on boarding school grounds, to know definitely what became of loved ones and to demand accountability.

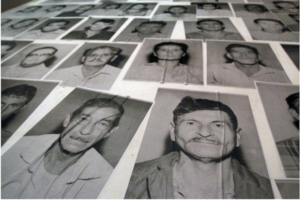

Memory is an essential and powerful force in these efforts. Disappearing someone is a form of trying to erase their existence. Keeping alive the memory of the disappeared, their identities as members of a community, is a central work of COFADEH in Honduras. COFADEH’s motto is, “Somos tu memoria” (We are your memory). Memory, especially group and collective memory, is the way of ensuring that the presence of the disappeared remains. At the start of many meetings of popular organizations and human rights groups in Latin America, the names of the community’s disappeared are called out and the response is “Presente!”

Peace House is a sponsor of accompaniment for the Committee of Families of the Detained, Disappeared in Honduras. This accompaniment provides a measure of protection and international witness that may help to dissuade the many threats that COFADEH’ s general coordinator and staff members have received in its 40 years as an organization. We congratulate COFADEH as it celebrates 40 years of working for the disappeared, and twenty-two years of its radio program, Voces contra el Olvido (Voices against Forgetting).